As the founder of SOOT, Jake Harper (JH) is working on reinventing how data moves through space. Previously, he designed how robots communicate with humans at Zoox. As a sound artist he is most known for his work with sirens.

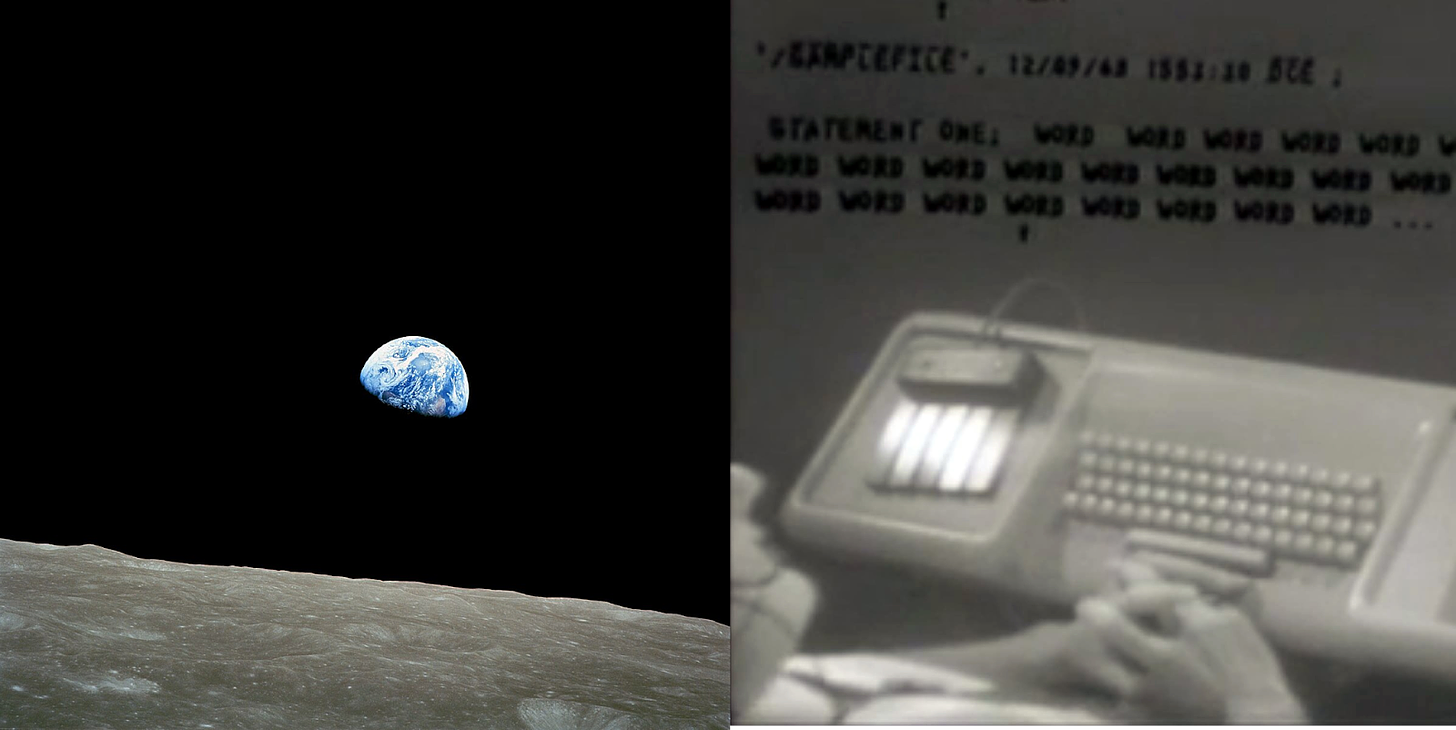

Jake here. In a curiosity of symmetry, 1968 saw two revolutionary moments that changed how humanity saw itself: the first color photograph of Earth from space, and the debut of the first graphical user interface (GUI).

On Christmas Eve, the crew of Apollo 8 captured "Earthrise," showing our planet as a fragile blue marble floating in the cosmic void. Just weeks earlier, Douglas Engelbart had demonstrated what would become known as "The Mother of All Demos." Over the course of 90 gripping minutes in San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium, Englebart revealed the first ever demonstration of a computer mouse, hypertext, multiple windows, video conferencing, word processing, and real-time document collaboration.

More importantly, a black and white screen displayed all of the information in his computer in a readily understandable interface - the first ever GUI. These breakthroughs arrived during a year of global upheaval – the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, widespread protests, and the Prague Spring.

Why is this interesting?

The simultaneity of these two developments – one showing us our physical place in the universe, the other unveiling new ways to see and understand information – marked a profound shift in human consciousness. The Earthrise photo sparked an environmental awakening, helping launch the first Earth Day in 1970 and leading to the creation of the EPA. Meanwhile, Engelbart's GUI demo laid the groundwork for personal computing and how we interact with digital information today.

What's particularly fascinating is how both innovations were driven by a similar impulse: the desire to see everything at once. Stewart Brand, founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, had been campaigning throughout the 1960s with buttons asking: "Why haven't we seen a photograph of the Whole Earth yet?" He understood intuitively that such an image would change our perspective fundamentally. Similarly, Engelbart's mission at the Stanford Research Institute was to "augment human intellect" by creating tools that would help people better understand and navigate complex information spaces.

Both breakthroughs required extensive technical innovation. NASA collaborated with Hasselblad to create a custom camera that could work in extreme temperatures and with special Kodak film to maximize shots per roll. Engelbart's team rigged a complex system of cameras, microwave links, and a custom modem to transmit both visuals and commands between a computer in Menlo Park and his demo unit in the San Francisco auditorium. But the real achievement in both cases was conceptual – they showed us new ways of seeing. The Earthrise photo revealed our planet's unity and fragility, while the GUI demonstrated how computers could become tools for thought used by everyone, rather than just a calculation machine for a select few.

It would take another 16 years for Engelbart’s dream to actually begin landing in every home and office (with the release of the Mac One in 1984, the first truly successful commercialization of a personal computer). In this respect, 1984 gave a semblance of fulfillment to some of the ‘68 generation’s revolutionary aspirations, as symbolized in the Mac One’s Super Bowl commercial, which referenced George Orwell’s classic dystopian novel “1984”.

Directed by “Blade Runner” director Ridley Scott, the ad features a female action hero athletically infiltrating a theater filled with zombified slaves clad in carceral uniforms, hypnotized by the lectures of a tyrannical face projected on a giant screen. Orwell’s “Big Brother,” or the personification of what 1960s beatniks might have called “The Man”, recites a succession of totalitarian slogans devoid of substance, parodying IBM’s perceived monopolistic grip on the computer industry and its failure to market truly user-friendly personal computers. Fearless, the stuntress spins around and hurls a massive sledgehammer at the screen, shattering the image of this oppressive paper tiger. A beam of light liberates the crowd from its conformist slumber as the prophetic voiceover announces: “And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.”

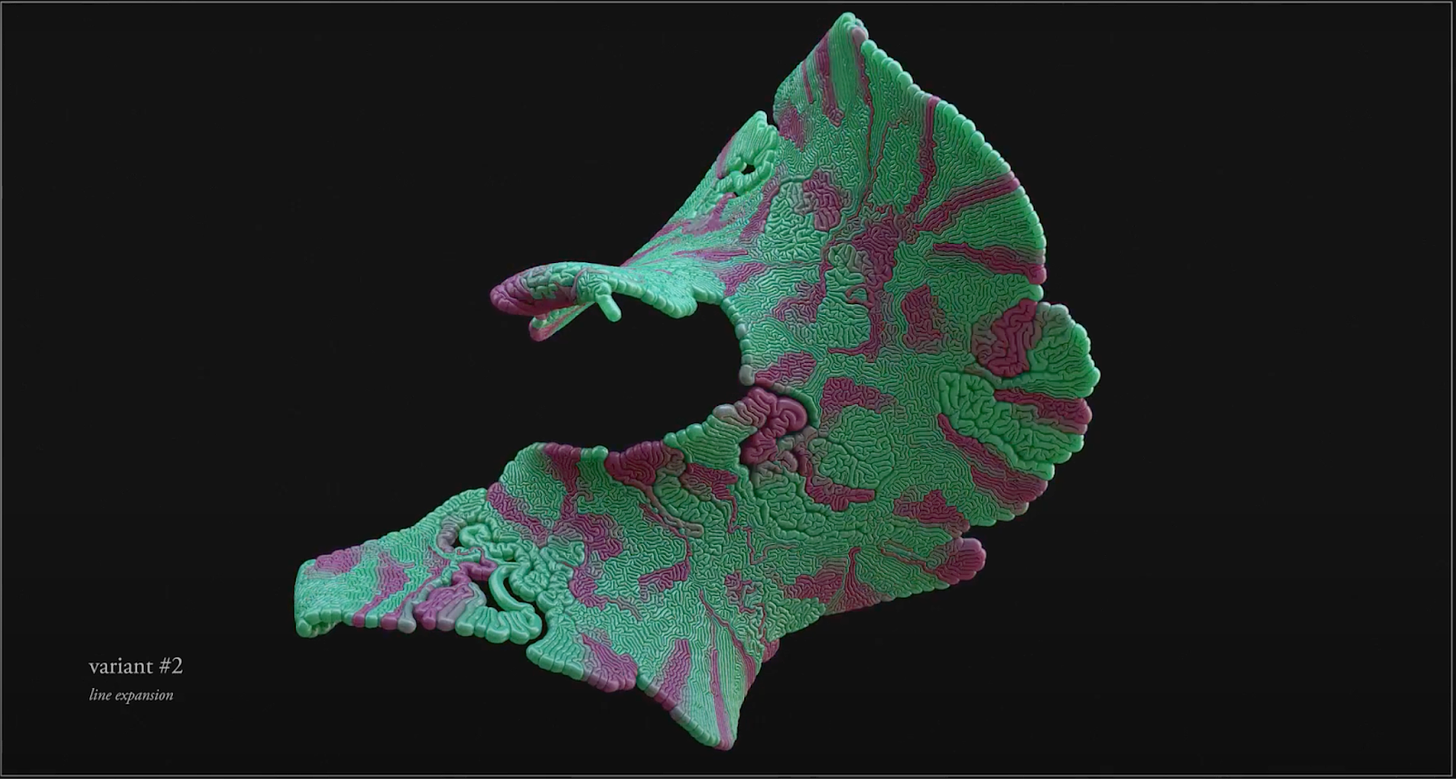

Since Earthrise, human vision beyond our planet has continued to extend. Now we can even theorize about the unobservable interior of black holes by studying their surface properties. Which begs the question: what has the GUI become? If you squint, Engelbart's demo machine tracks remarkably to the modern personal computer (mouse, keyboard, windows, real-time document editing), with obvious improvements. However one limiting feature remains surprisingly unchanged - one so deeply connected to the architecture of the GUI that you might not even realize it is a design choice: the line.

Nearly every computer interface reduces to this simple geometric shape. From news feeds to social media to file systems, our digital interactions are confined to linear streams of information. In 1968, when the first GUI connected to a 2-megabyte computer, a line could show nearly everything. Today, this same form struggles to parse an unprecedented volume and complexity of information.

The line's persistence reveals how computers have evolved from tools for augmenting intellect into engines of engagement. We even call it "the feed" now – a term borrowed from industrial farming, where linear conveyor systems deliver a constant stream of nutrients to continually fatten cattle for market.

It's tempting to view this transformation as simply one more example of technology's inevitable trajectory from utopian beginnings to capitalistic exploitation before obsoletion. Has the despot from Macintosh’s 1984 commercial permanently won, his mind-numbing mantras to forever hold us in a state of passive confusion?

But there’s another contributing factor: we've just hit the bandwidth limit of linear geometry. When information perpetually vanishes into infinity by design, there's no more value left to extract from the interface other than to bore into the user’s mind, fixing into their attention.

Nature, when faced with similar spatial constraints, employs curvature: DNA coils pack six feet of genetic code into microscopic cells; the brain's folded surface maximizes its processing power. Leaves utilize curvature to expand their light-collecting surface area within a crowded forest canopy. Nature abhors flat planes and lines because they are structurally weak and poor containers for information. Our interfaces remain stubbornly straight for now. (JH)