The Apple ATT Edition

On privacy, app tracking, and attribution

Rick Webb (RLW) used to be my boss (and Colin’s too) during our time at The Barbarian Group, which he co-founded. He is a prolific writer, thinker, podcaster, and consumer of media. He’s also the only person I’ve ever met who thinks and speaks in bullet points. - Noah (NRB)

Rick here. Sometime soon, maybe by the time you read this (no one knows exactly when), after months of delay, Apple will begin enforcement of its new, much-vaunted App Tracking Transparency (confusingly, ATT—sorry AT&T) framework and protocols. In the world of in-app advertising, this is a very big deal. You may have heard about it. Forbes has called it “stunning.” This may be hyperbole, but only just.

Keeping this WITI in the language of the layperson, Apple’s privacy changes come in three main parts:

Requiring apps to gain explicit consent to “track” users across the internet with their advertising.

Revamping what’s called in the biz attribution: the way in which advertisers confirm who was really responsible for a purchase, or a click.

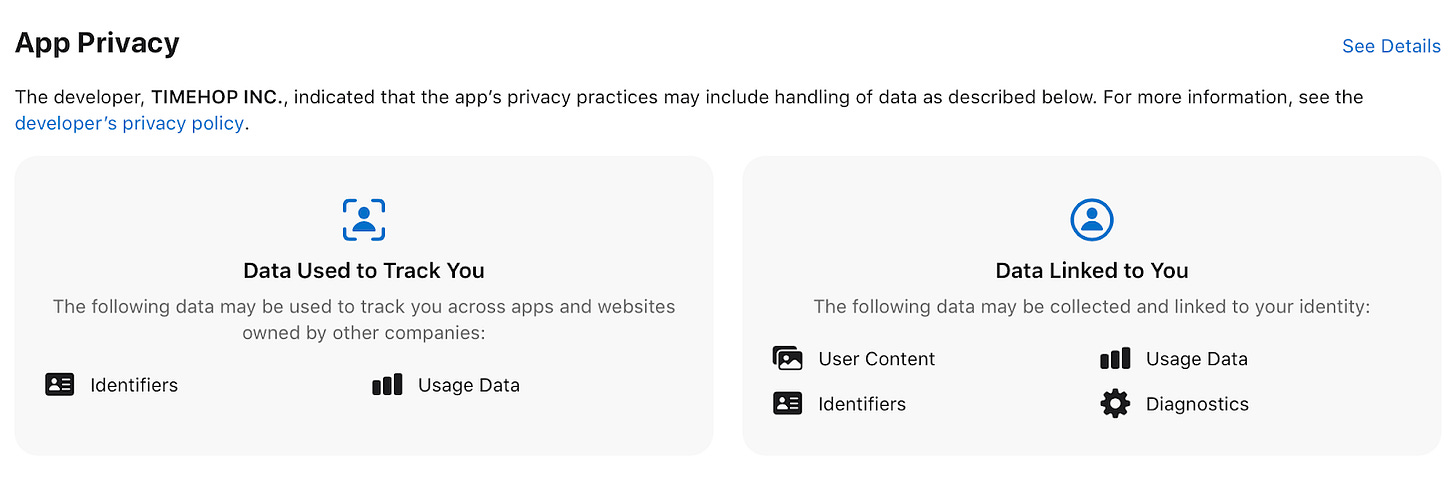

App privacy “nutrition labels,” visible in the app store, clearly explaining to people how and when an App uses their data.

Of the three, the nutrition labels are perhaps the most clear-cut and least controversial. The other two have brought about significant amounts of blowback from the industry. Perhaps best-known is Facebook’s five-barrelled ad campaign against Apple’s privacy changes. Apple itself has stepped into the fray with marketing touting how evil everyone else is, and positioning these changes as nothing less than a moral crusade. Most of us like the idea of data privacy, and most of us find the concept of “ad tracking” creepy, so Apple probably has the moral high ground here.

Why is this interesting?

Generally, I am a huge proponent of data privacy and applaud the general gist of Apple’s efforts. Yet there are few quirks to Apple’s implementation of ATT that is not widely understood, and leave one questioning their true motives.

First, Apple already offered the ability for users to control ad app tracking. For the last decade, iOS has included the IDFA—Apple ID For Advertisers—the primary method with which advertisers can “track” users. This has, since iOS 10 in 2011, been an anonymous ID, that can be turned off or reset (prior to this Apple let apps access the device ID, which could not be reset). Apple has not actually offered a new ability to “turn off tracking” in iOS 14.5, rather, what used to be opt-out is now opt-in. They’ve also updated the granularity with which users can control this choice: previously the option was universal for all apps, but now it can be turned on or off for each individual app. To me, this is hugely fascinating and under-discussed. Most news articles present this feature as new, but I find it far more interesting than a simple change in choice architecture (from opt-out to opt-in) can, potentially, threaten an entire industry. No one knows exactly how many people will opt out, but everyone assumes it will be much higher than it was in the past. If you choose to not opt out, you will still get an ad. It will probably be a “worse” ad, of the punch-the-monkey variety. But that’s just a guess. As I said, no one knows.

Next, in perhaps the weirdest move, Apple has made no provision for GDPR, the EU’s robust, opt-in based, plain-language requiring privacy regulation. This leaves every EU iPhone user now facing the somewhat absurd task of opting in twice on every app. I am not an engineer (anymore), so I can’t say if this was a technical limitation or what. But it’s hard to see how this furthers privacy (GDPR is a very solid privacy law), and it’s hard to see how this holds up Apple’s famously user-centric design simplicity.

Most controversially, Apple has decided to prohibit users from opt-in to ad tracking in order to gain new functionality within an app. In the paid-app ecosystem, a user playing a game on their iPhone may decide to pay extra cash for a new level in the game (with Apple taking a cut). In the free app ecosystem, Apple has decided that users cannot do the same, paying with their personal information (via ad tracking) rather than money. The app has to have the exact same functionality, whether or not the user opts-in to ad trafficking.

One can envision a world where the user is in complete control of their data, and only lets certain apps use it. But it’s very odd that Apple has unilaterally mandated that I can’t get something in return for letting an app use my data. Some people find exactly this mechanism of exchange to be a worthwhile vision for the future of data privacy. Yet Apple has decided to forbid this. Apple’s defense of this is that “apps should allow a user to get what they’ve paid for” even though… the app is free? And Apple’s not letting users pay with opting-in.

Regarding attribution, Apple has made a fantastic new privacy-first attribution framework called SKAdNetwork. It seems legitimately great, and will hopefully go a long way toward curbing some of the abuses in this area. One thing that seems very odd, however, is Apple’s seemingly arbitrary declaration that a purchase or click can only be attributed to one source. If you read a blog post about a camera, and it embeds a Youtube review, and that Youtube review includes a link to buy, under the old system, the blogger and the Youtuber could (theoretically) share the credit (and potential affiliate revenue). Now? Only one can. There may well be technical reasons for this—Apple hasn’t elaborated on the decision—but, in real-world marketing, most modern attribution ties to multiple sources.

Tim laying down the law at Brussels’ International Privacy Day

To me, the most interesting thing about all this is no one knows what’s going to happen. Many ad tech companies (like Facebook!), and some app publishers (like me), worry that this may decimate their revenue or even put them out of business. Then again, maybe it won’t. Yet Apple has decided there’s only one way to find out, and they’re gonna go for it. Damn the torpedoes. The end justifies the means, etc., etc.

Most of the anti-monopolists out there seem to support Apple’s moves, which seems… odd. That one of the world’s largest companies is going to maybe (or maybe not! who knows!) put a bunch of smaller companies out of business and is generally being applauded for it, and no one seems to find it anti-competitive is, I think, unprecedented. This is also interesting since many observers—such as Eric Benjamin Seufert over at Mobile Dev Memo—have placed these changes squarely within the larger narrative of Apple’s ongoing battles with Facebook. He’s also posited that Apple’s moves may have profound unintended consequences, leading to further media consolidation and what he calls content fortresses. And it’s going down all while Apple implicitly encourages companies to maybe reconsider their business model and switch to a model where Apple can get their cut. (RLW)

Mask of the Day:

We’re friends of Outlier here at WITI. This one is “bank robber from the future chic.” Described by the brand as, “An experimental non-medical mask. Soft Ultrasuede against the face for comfort and, as best we can tell, great filtration. Open yet opaque Injected Linen on the outside for breathable coverage. A magno-mechanical Fidlock closure for easy donning, doffing, and adjustment.” (CJN)

Quick Links

Fabergé is making a new egg: A dragon egg inspired by Game of Thrones. (RLW)

Heat pumps! (RLW)

Toyota unaffected by car microchip shortage thanks to a business continuity plan instituted after Fukushima (RLW)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Rick (RLW)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).