Ryan Anderson (RJA) is a freelance marketing exec based in Atlanta, GA. He has written a number of previous WITIs including Video Assisted Review, Semiconductors, and Simpson’s Paradox. An earlier version of this edition first appeared on his Proper Tack newsletter.

Ryan here. Batteries are everywhere. They’re in whatever you are using to read this email right now.

Lithium-ion batteries were first commercialized 30 years ago by Sony, in partnership with the Japanese chemical company Asahi Kasei, and have become a defining part of our lives. In recent years batteries have famously made the leap from our personal electronics to our cars. If you don’t yet have an EV, you probably will soon, as the industry continues to shift away from internal combustion. Car companies have even started dramatically increasing their marketing budget to help ensure consumers follow their lead.

But all is not well in lithium-ion land.

Prices for lithium carbonate in China, the world’s largest EV market, quadrupled over the course of 2021 to $36,514 per ton. Ford’s CEO is more worried about battery supply than semiconductors. And if you read the past WITI on semiconductors you would know how big of a deal that is!

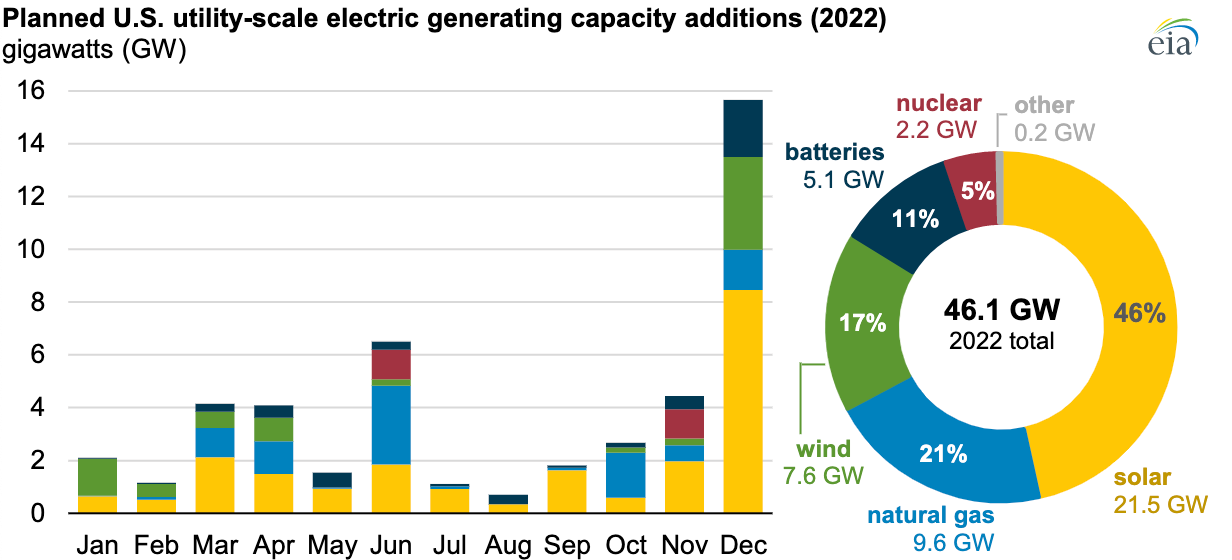

The demand for lithium-ion batteries expands far beyond consumer products. These could be batteries in your home to retain excess power generated by rooftop solar panels, or grid-scale batteries for the same general purpose on a larger scale. This is important as solar and wind power are projected to account for over 60% of new power generation coming online this year in the US.

Why is this interesting?

Right now we largely think of energy storage as a chemical process. You’ve got the alkaline batteries that go into remote controls and bedevil parents every Christmas morning. You’ve got the lead-acid batteries that internal combustion engines use to power their starters. You’ve got lithium-ion batteries and dozens more.

Thankfully, there are a number of new energy storage solutions in the works that may help us more fully rely on clean energy generation.

One of the more intriguing—and at first counterintuitive—examples is what I’ll call mechanical storage.

Parts of the world have actually used this for a long time through what’s known as pumped storage. Basically, you use excess energy to pump water up a hill into a reservoir. Then, when you need power, you let the water run down and spin a turbine. The Bath County Pumped Storage Station in Virginia can store about 24 gigawatt-hours of energy this way. To put that in context, the island of Oahu has a peak load of about 1.2 gigawatts, so a full BCPSS could power the entire island at peak load for 20 hours.

The problem with pumped storage is that it needs a hill and two reservoirs (a lower that typically holds the water, and an upper that you pump the water up to). You can build a hill and some reservoirs, but that costs a lot of money. Typically these are installed where the terrain already allows for it. So mountains. You also need water. And in areas like the quickly-drying American West, that can be problematic.

The good news is that you can lift much more than water. Energy Vault is beautiful in it’s simplicity. It works like pumping water uphill, only instead it lifts 35-ton concrete blocks. When you need energy you start lowering a block, which spins a turbine, which generates electricity.

If lifting something up isn’t your thing, you can also push stuff down. Hydrostor is trying to solve energy storage by pumping compressed air into the ground and then releasing it when energy is needed. As the air comes up it spins a turbine, which generates electricity. You see the pattern.

Beyond these mechanical storage solutions, there are also some interesting chemical alternatives including iron air batteries and green hydrogen.

While these storage formats aren’t going to make it into your car any time soon, it does start to expand the idea of batteries. And with increasing home usage it starts to open up new size and weight possibilities that weren’t possible when batteries needed to fit in pockets. Given the realities of lithium (we may have 90 million tons left), the race is on to find new ways to store energy and power our world. (RJA)

__

Partner post: The Daily Upside

If you love what we write every day, you likely value intriguing and thought-provoking stories. The Daily Upside, founded by a team of bankers and journalists, is WITI but for business news. Built with investors in mind, The Daily Upside is packed with analysis and stories you simply won’t find elsewhere. We like it as it strikes that elusive balance of gravitas and wit.

There’s a reason 250,000 readers start their day with The Daily Upside. Join today for free.

--

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

Sporting Goods 2022: What do sneakers have in common with Coco Chanel? According to the founder of a running-shoes company, in the past two years the global industry has seen a major shift, “comparable to the 1920s when [Chanel] liberated women from corsets.” A new report, from the World Federation of the Sporting Goods Industry and McKinsey, reviews the market and dives deeper on five trends that could reshape it.

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Ryan (RJA)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).