Emanuel Derman (ED) started off with WITI with the excellent Japan edition. He grew up in Cape Town, South Africa, and came to Columbia University in New York to study for a PhD in physics. His memoir of youth in a postwar Polish-Jewish immigrant community in Cape Town, South Africa will appear later in the year.

Emanuel here. The instructor in my watercolor class is very good. When the model takes a break, he invites everyone to stand behind him while he demonstrates how to do different kinds of washes.

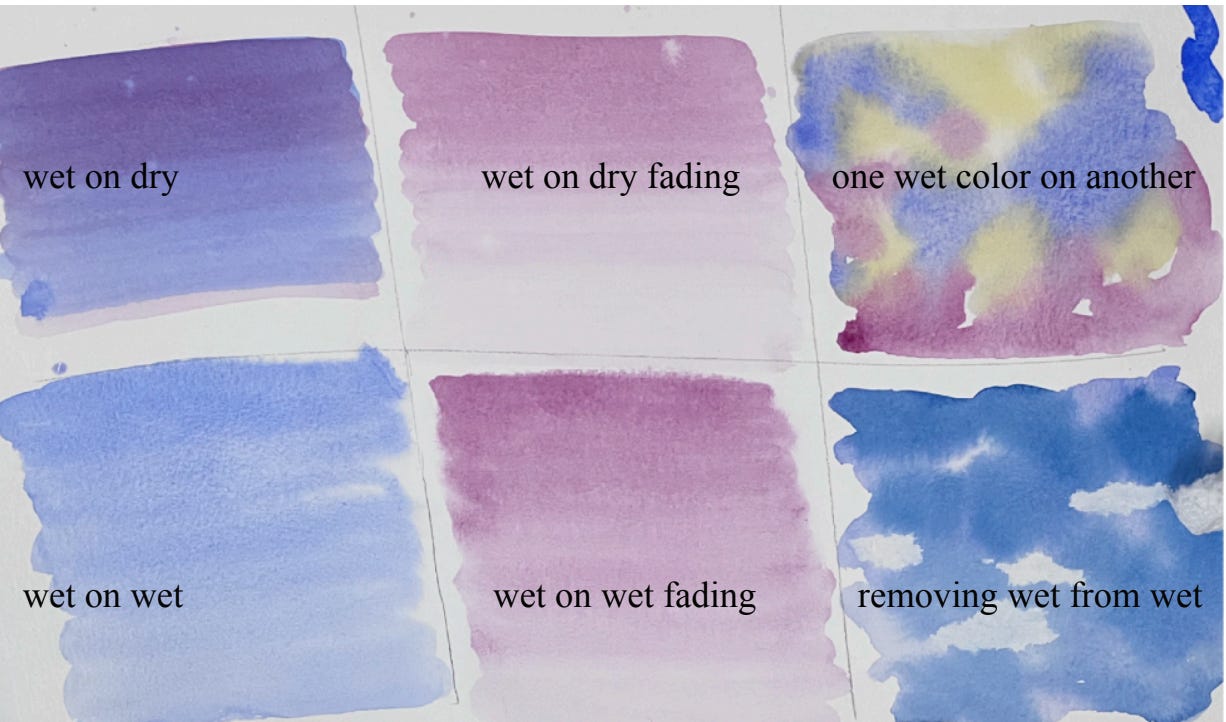

You can paint wet on dry, i.e. putting wet paint on dry paper. As you keep moving your brush—initially loaded by just one good dip in the paint—back and forth down the paper, the color slowly thins as the brush empties, but stays fairly precisely in position. With wet on wet, the paint flows along the wet paper and gives looser imprecise boundaries with more random variation. Some people like to tilt the paper to guarantee more flow.

Or you can do what I call fading: you pause after a few back-and-forth strokes, rinse all the color from your brush, dip it in water, and then continue back and forth from where you left off, dragging a bit of the paint from the previously final brushstroke down the paper as its color dilutes and lightens.

The model never sits still for longer than 20 minutes. The main aim the instructor impresses on everyone during the breaks, is to have soft boundaries between the dark and light, to “smooth the edges.” Somewhat like this, though it’s way not smooth enough.

It has too many sharp boundaries. To eliminate them you have to sort of fade the darker color into the lighter while they are still wet. There are some really talented people in the class, experienced too, and they all achieve a fluidity I cannot get to. Their paintings are low on detail but strong on darks and lights, somehow capturing the sense of the whole body with mere suggestions. Your eye does the rest.

Part of my trouble is speed; the watercolor dries in 30 seconds or so. Also, I’m temperamentally drawn to the minutiae. I aim for much too much detail and. I want to make corrections. My brain says watercolor but my heart says gouache.

Why is this interesting?

Because the surface you paint on determines what you can achieve.

One trouble with trying to get detail when using watercolor is that paper can easily get waterlogged and then buckle. Cold-pressed paper, which most instructors seem to demand, is rougher and the paint on it looks more imprecisely authentic. Hot-pressed is smoother and allows better detailing. But either way you can’t mess around for too long. 140 pound paper can withstand at most a couple of glazes, i.e. successive applications of a wet brush. 300 pound paper, I’m told, tolerates a few more. I’ve sometimes thought of minorly splurging on 300 pound paper to give myself more latitude to fix mistakes, but not yet. Only when I’m ready for a masterpiece …

The other evening the instructor stopped by my seat for a while and changed his tune a bit, indicating it was ok to do things differently. He used his phone to show me, for encouragement, some really detailed paintings by someone called Ali Cavanaugh whose work he liked.

I wondered how her paper was able to withstand so many glazes, although you can see “blooms” where too much water on the brush has muddily pooled when making a correction over previous paint. That would be a flaw for me, but in her case it’s not a bug but a featureit’s her style...

I googled her and it turns out she paints on something called Aquabord, a framed canvas-like board which the company that makes it says is “coated with an acid-free clay and mineral ground with a texture similar to cold-pressed watercolor paper.” It allows “endless glazes, and easily lifts colors back to the white of the surface to create depth and highlights.” She calls her paintings on this medium modern frescoes.

I like the advice she gives in an interview on the web:

Don’t limit yourself with perfectionist thinking that there is a “right” or “wrong” way to paint. I always say to artists—remember that you are on a journey. Don’t look at your paintings as individual masterpieces, putting that kind of pressure on yourself is creative suicide. Look at each piece as a stepping stone to the next painting.

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Emanuel (ED)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).