Noah here. Yesterday I found myself reading about pigeons.

Take this story of President Wilson, a US military carrier pigeon who helped transport a message requesting air support during World War I:

On the morning of 5 October, 1918, [President Wilson’s] unit came under attack and was heavily engaged in a firefight with the enemy. President Wilson was released to deliver a request for artillery support, flying back to his loft at Rampont some forty kilometers away; he drew the attention of the German soldiers who fired a nearly impenetrable wall of lead blocking his path. Despite this, President Wilson managed to deliver the lifesaving message within twenty-five minutes — a record for speed — unmatched in the American Expeditionary Forces. When he landed, his left leg had been shot away and he had a gaping wound in his breast.

It’s a hundred years later, and we still aren’t quite sure how homing pigeons do it. There seems to be some agreement that they have an internal magnetic compass for orientation. But that still doesn’t answer how they know the direction of their goal. This requires a map, and there are a bunch of different theories on how that works. One suggests they’re using magnetic fields for mapping and orientation, while another suggests they smell their way there. “It’s likely that birds learn the rough composition of atmospheric volatiles characteristic of their home area and how this varies with winds that come from different directions,” explains The Conversation, “and are then able to extrapolate to unfamiliar places if they are blown off-course or taken there by a human and released.” A third theory suggests they use infrasound—super low-frequency sound—to “hear” their way home.

Why is this interesting?

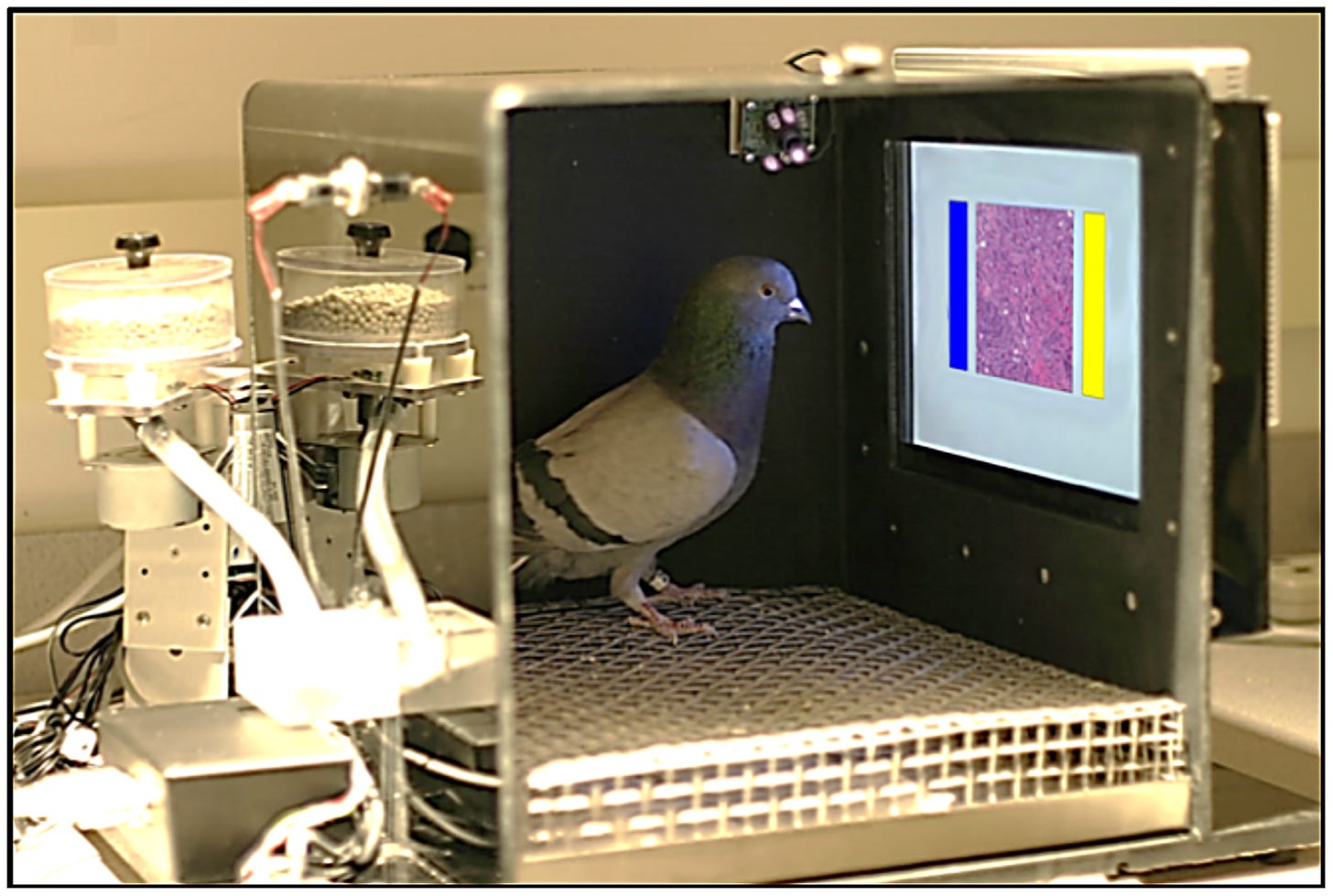

Beyond this ability to navigate, apparently, pigeons have a very advanced visual system. So advanced, in fact, that a recent paper experimented with using pigeons to help read radiology reports. “The birds proved to have a remarkable ability to distinguish benign from malignant human breast histopathology after training with differential food reinforcement,” the abstract explains. “Even more importantly, the pigeons were able to generalize what they had learned when confronted with novel image sets.” This isn’t to say we’re going to turn radiology over to the birds anytime soon, but pigeons can “help us better understand human medical image perception, and may also prove useful in performance assessment and development of medical imaging hardware, image processing, and image analysis tools.”

This is far from the first time we’ve tried to use pigeons for their visual abilities. This radiology experiment led me back to this story from World War II where the behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner got the military to pay for him to try to train pigeons to steer missiles. “Skinner divided this nose cone into three compartments, and proposed strapping a pigeon in each one. As a bomb headed towards earth, each pigeon would see the target on its screen. By pecking at the image, the birds would activate a guidance system that would keep the bomb on the right path until impact. Skinner's idea received initial support, but the U.S. military finally dismissed it as impractical.”

Here’s the nose cone (it was built for three avian pilots):

And the real inspiration for this WITI, the insane gif of a pigeon guidance system in testing. The pigeons wore a metal conductor on their beak for transmitting pecks.

Unsurprisingly, the military eventually shut the project down. But it’s a testament to nature that to this day we are still finding ourselves amazed by a bird we regularly shoo away. (NRB)

Lamp of the day:

The Akari Light Sculpture Model 1N!

Quick Links:

How Bezos beat the tabloids (CJN)

Six lessons for the modern strategist (CJN)

The FT talks to Brian Chesky (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).