Colin here. I’m disappointed by a lot of the travel reportage that gets published in magazines and newspapers these days. But WSJ Magazine recently ran something that caught my attention: a nuanced piece on a remote island off of Yemen called Socotra. It’s not easy to get there, you must fly from Cairo via Aden or take a flight from Abu Dhabi on Etihad, which runs infrequently. But visitors are rewarded for their journey with an otherworldly place, with flora and fauna that doesn’t exist elsewhere. WSJ explains:

The island sits between the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea, closer to Africa than to the Arabian Peninsula, and was once part of a much larger landmass that broke off as the continents formed. No land mammals survived its isolated evolutionary path, but an impressive range of plants and reptiles did.

Why is this interesting?

While the story weaves a fascinating narrative through geography, conflict, isolation, and ecology, I was struck by an otherworldly tree the writer visited. Turns out it is both beautiful and useful.

320 species are endemic to the island. A certain type, called Dragon’s Blood, has bloomed here for thousands of years. It doesn’t grow anywhere else. According to the Center for Biological Diversity:

Native to a single island in the Socotra archipelago, off the coast of Yemen in the Arabian Sea, the extraordinary-looking dragon’s blood tree, which is classified as “vulnerable to extinction,” can grow to more than 30 feet in height and live for 600 years. Looming over the island’s rocky, mountainous terrain, it produces rich berries and a vermilion sap — the source of its name — that has been used for centuries as everything from medicine to lipstick, and even as a varnish for violins.

Some of that benefit comes from its medicinal properties. The name comes from the red sap the trees produce, which was rumored to be prized by Roman warriors as a cure-all for wounds.

According to the Sinchi foundation: “Dragon’s Blood sap is a rich, complex source of phytochemicals including alkaloids and procyanidins (condensed tannins). Internally, it is an important remedy for gastrointestinal issues.”

The trees are also important to the overall ecology of the place. And, like many things, are now endangered by rising temperatures and altering monsoon patterns. Once predictable, they have become irregular, thus contributing to dryness on the island. The WSJ profile continues:

“The physical structure of the dragon’s blood trees, optimized to capture moisture and channel it to the soil, makes them uniquely susceptible to damage from new kinds of weather events,” he says. On a recent visit, his first since war broke out, Attorre and his colleagues estimated that thousands of trees had been wrecked by cyclones in the past five years. Most of the trees were believed to be around 500 years old; others were even more ancient. Attorre sees little hope for their survival—unless the Socotrans can find a way to nurture and protect forests that took centuries to reach maturity.

It’s fun to disappear down wormholes with WITI, and this piece of reportage certainly made me do it. And the Dragon’s Blood tree, though it has a fearsome name, reminded me a bit more of the giving tree in what it has offered the island and society with its ecological role and medicinal benefits. One can only hope steps are taken to keep it around. (CJN)

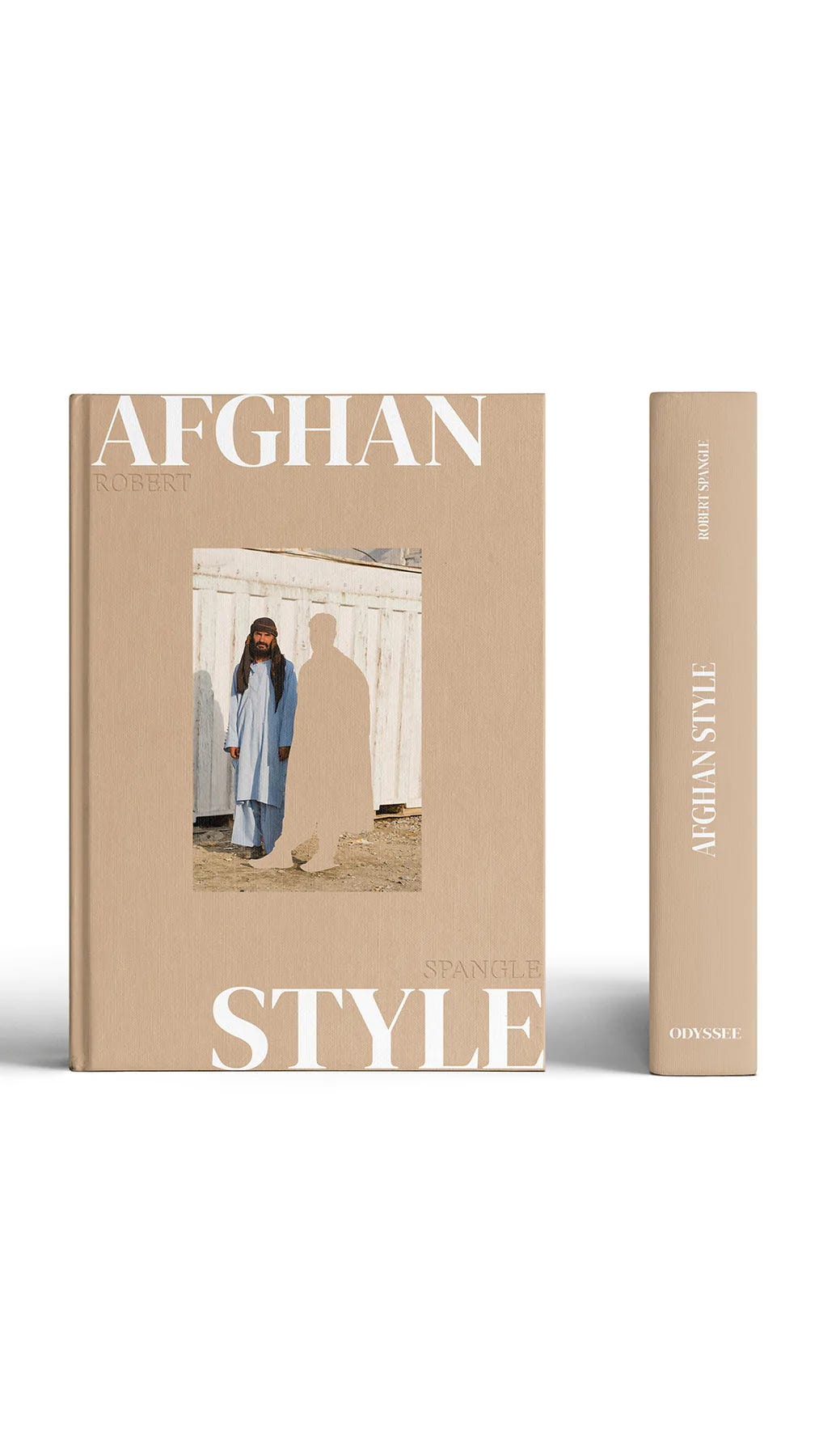

Pre-order of the day:

Friend and WITI contributor Robert Spangle has a new book coming out, called Afghan Style. You can order it on his Observer collection website.

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.

Loved the Dragon blood tree article...