It’s Formula One season again, and with that, a chance to re-run an old favorite about F1 sponsorships. - Noah (NRB)

Noah here. If you tuned into F1 in Bahrain this weekend, you would have been treated to an all-time season opener that came down to the final laps between Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen, two of the sport’s best drivers. You also would have seen team Ferrari bringing home a respectable finish after a disappointing campaign in 2020.

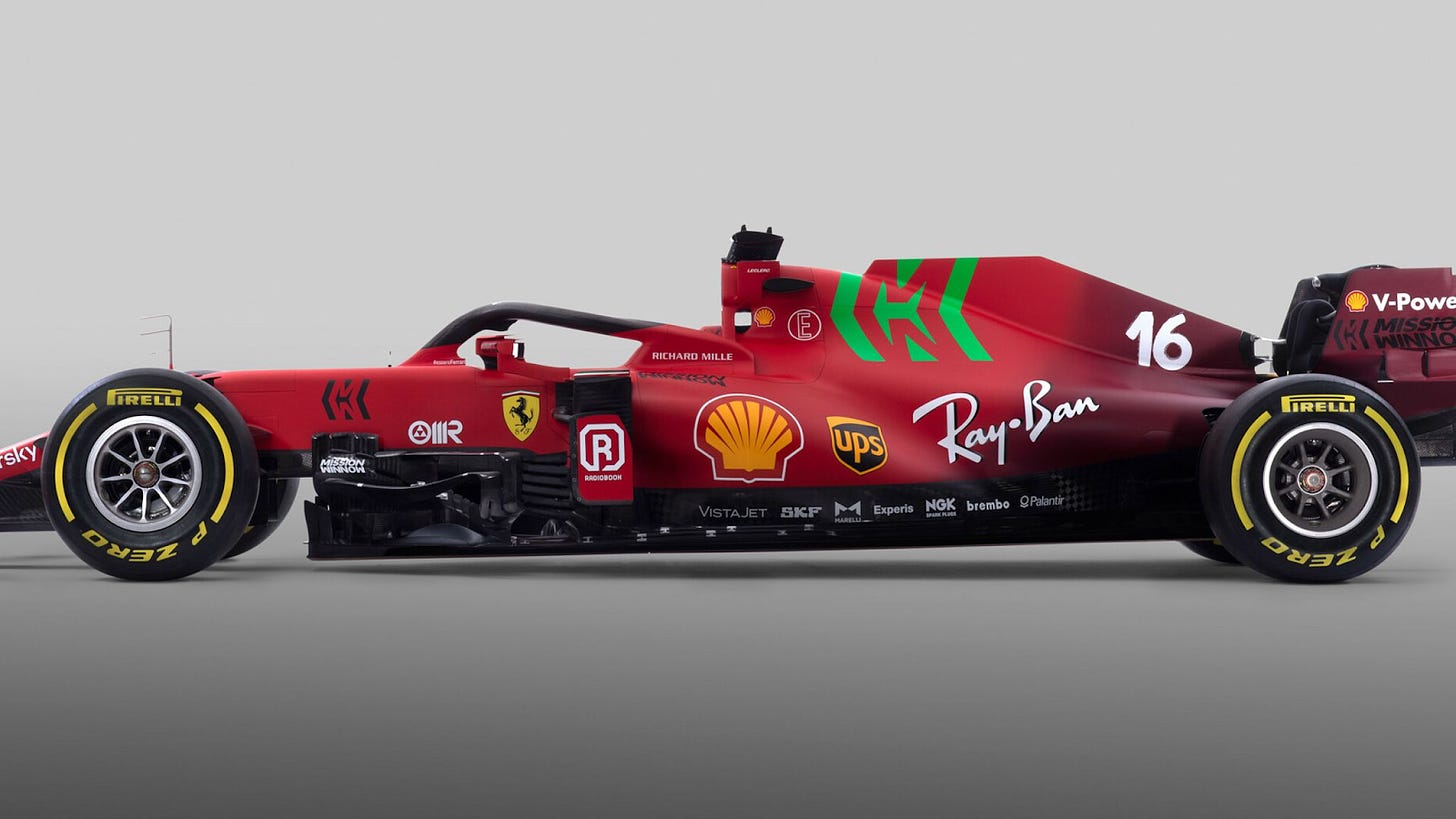

Ferrari’s 2020 car accents their iconic red with a splash of green near the top—a mirrored logo that likely means nothing to more than 90% of the viewing public. The green “M” and “W” stands for Mission Winnow, a brand that, as far as I can tell, sells nothing at all. A stroll through their website offers up a very generic mission (“drive change by searching for better ways of doing things”), lots of modern design, and a Phillip Morris logo at the bottom. Mission Winnow, it turns out, is a division of Philip Morris International (PMI).

Why is this interesting?

Tobacco and racing have a long history. Some of the F1’s most iconic cars carried cigarette branding, including McLaren’s world-beating cars from the early 90s.

Like many things having to do with cigarettes, tobacco sponsorships took a turn in the early 2000s as European countries started regulating and eventually banning tobacco advertising. At that time, PMI and Ferrari began to find more abstract ways to display the Marlboro branding, peaking in 2008, when they drove with a red, black, and white barcode that looked a lot like a bunch of cigarettes/the Marlboro logo stretched out.

In 2010 the team took heat when British doctors accused Ferrari and PMI of subliminal advertising. “The barcode looks like the bottom half of a packet of Marlboro cigarettes,” explained John Britton, a fellow of the British Royal College of Physicians and director of its tobacco advisory group. “I was stunned when I saw it. This is pushing at the limits. If you look at how the barcode has evolved over the last four years, it looks like creeping branding.”

The Ferrari team responded pretty defensively to the allegations:

Neither of these arguments have any scientific basis, as they rely on some alleged studies which have never been published in academic journals. But more importantly, they do not correspond to the truth. The so called barcode is an integral part of the livery of the car and of all images coordinated by the Scuderia [the name of the Ferrari team], as can be seen from the fact it is modified every year and, occasionally even during the season. Furthermore, if it was a case of advertising branding, Philip Morris would have to own a legal copyright on it.

Later that year, the team was pushed to remove the barcode by the sports governing body, but that didn’t end the sponsorship. PMI extended the deal in 2011 and again in 2015, despite agreeing to remove the Marlboro name from its Scuderia Ferrari Marlboro moniker in the years in between. As far as I can tell, in 2018, Mission Winnow came on the scene with a logo full of chevrons, a bunch of Tweets that read like motivational posters, and a very vague mission:

Mission Winnow has a simple goal: drive change by constantly searching for better ways of doing things. From world-leading engineers and scientists to cutting-edge creatives, the people at PMI, and our partners at Scuderia Ferrari and Ducati, have the know-now to challenge the status quo, drive revolutionary change and to be champions.

Not shockingly, folks are still pretty suspicious. A February 2019 editorial from BMJ, a peer-reviewed medical journal out of Britain, suggested that this looks a lot like the same old behavior. “It appears that the Mission Winnow campaign is based on similar arguments relating to the Ferrari barcode design in 2010. Mission Winnow appears to be using the power of persuasion and their history of both active and subliminal advertising of Marlboro in F1 and MotoGP to continue promoting this association.” Australia and Canada forced Ferrari to drive without the Mission Winnow branding as they consider it tobacco advertising.

In the end, the real question is, what is PMI doing? It seems to me there are two possible explanations: either it’s true that the Marlboro brand is so strong that all they need is some shapes and colors in red, black, and white to deliver meaningful brand impressions (not an unreasonable thesis), or there’s an executive at PMI that loves going to F1 races enough that they’re happy to waste hundreds of millions of dollars to make that dream a reality (also not unreasonable). In the end, I would guess it’s a little of column a and a little of column b, which makes for one of the strangest stories I’ve ever encountered in marketing. (NRB)

Radio Show of the Day:

Though it might not have the most appealing name, Terrible Records is an excellent show on the always reliable NTS, a streaming station in London. (CJN)

Quick Links:

Reverse Engineering the source code of the BioNTech/Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine (NRB)

Speaking of F1, and connecting back to my Low-Rake Edition: New aero regulations cost low-rake cars 1s per lap (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).