The Forster Craft Sticks Edition

On producing six billion toothpicks a year, salesman tricks, and family activities.

Ryan Anderson (RJA) is a freelance marketing exec based in Atlanta, GA. He’s written WITIs about counties, statistical paradoxes, green hydrogen, sound in sports, and more. He has strong thoughts about how to build systems that enable performance and growth.

Ryan here. Every month, my kids receive a subscription box of craft activities in the mail. They love getting a package addressed to them, and the few hours of creation are a great way to spend a rainy weekend or a slow evening. As our kids have grown and their interests have evolved, we’ve subscribed to different versions of these. Thanks to the internet, it’s easy to find options for generic crafts, coding, or even cooking.

The lifespan of the creations vary. We’ve had “stained glass” art that hung on a window for years, and puppet show booths that didn’t make it through the weekend.

But none of these projects are permanent creations. Certainly, nothing created from these craft boxes will go on to be worth hundreds of dollars in 70 years.

Why is this interesting?

Because one such craft creation actually is worth hundreds of dollars today: the popsicle stick lamp. These are exactly what they sound like, a simple bulb kit and wiring surrounded by craft sticks glued together.

What started as simple square boxes with slatted shades quickly evolved in detail and artistry to the point that vintage examples can now sell for $700 or more. As best I could find, these lamps first started to appear in the 1940s, during the final years of Tramp Art’s popularity. The lamps’ expanding design complexity no doubt took inspiration from the movement’s focus on repurposing small scraps of wood into truly beautiful creations.

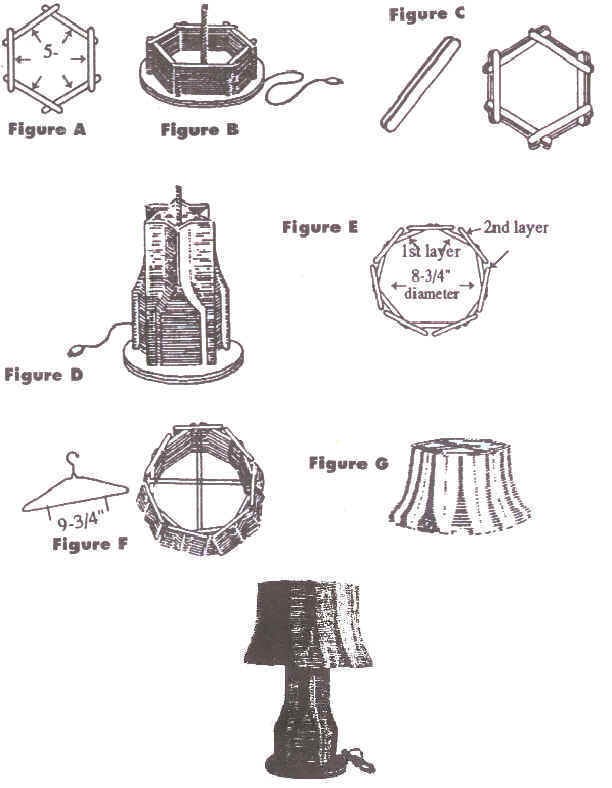

If free-crafting a 26-inch tall work of art out of 4.5” long obround sticks feels intimidating, you are not alone. Craft stick manufacturers realized that customers would be hesitant to purchase these materials without a plan in mind, so they began including project examples and instructions in the packaging.

Just like a subscription box nowadays might show up with all of the contents and instructions you need to create a working pom-pom trebuchet and a foam castle wall, these boxes included instructions for animal faces, baskets, “Swirley Christmas Trees,” and, of course, lamps.

Now, if you were buying boxes of craft sticks back then, chances are you were buying some from the Forster Manufacturing Company. In the 1940s, Forster was producing a wide variety of wood products across three mills in Maine, including craft sticks. But some 80 years previously, the antecedent of this firm had been founded by Charles Forster, for the sole purpose of manufacturing toothpicks.

Toothpicks of varying materials have been used by humans for over 5,000 years, but it took the industrial revolution for mass manufactured wooden toothpicks to take hold. Forster first encountered hand-whittled wooden toothpicks while working in Brazil for his uncle’s import-export business. After a little research, he realized that white birch wood, abundant in Maine, was a near-perfect substitute for the orangewood toothpicks he became familiar with in South America.

By the early 1860s Forster had secured a patent to manufacture toothpicks using a modified shoe-pegging machine originally developed by Benjamin Franklin Sturtevant. Now that Forster could create millions of toothpicks every year, the challenge was how to sell them. While wooden toothpicks were popular in South America and Europe, they had never established a foothold in America.

Forster put on his marketing cap and started targeting general stores, hotels, and restaurants with a simple strategy. First, Forster would send an accomplice into an establishment and ask if they carried toothpicks. When the storekeeper (or waiter, or hotelier) inevitably answered “No,” they would loudly voice their dissatisfaction, and storm out. Within the next 2-3 hours, a salesman would come into the store with a variety of goods including, you guessed it, Forster’s toothpicks.

By 1867, Forster was selling about 16 million toothpicks annually, or roughly 4 per New England resident. As more people saw the product and started using it, demand exploded. By the mid 1870s Forster was selling 500 million toothpicks per year. In 1897, he produced over 6.5 billion toothpicks. Competitors saw the opportunity and mills began opening around rural Maine.

In the post-WWII peak of the US toothpick industry, milltowns in Maine were producing over 75 billion toothpicks per year.

Forster died in 1901, but his mills lived on. Over time they produced an ever-expanding variety of wooden products, including craft sticks. Those craft sticks became popular enough that even as the company was sold multiple times (to Diamond Match Company, then Jarden Corporation, then Newell Brands), and the toothpick business fell off (the last Maine toothpick mill closed in 2003), the Forster brand name lived on.

Forster craft sticks now live under the Loew-Cornell brand, within the greater Newell Brands conglomerate. It means that, much like myself, these craft sticks have lived a life that began in Maine and is now centered squarely in Atlanta, GA. (RJA)

Creative essay on a very interesting niche!