Noah here. Now that things are feeling a bit more optimistic around COVID (in the US at least), some folks have started to rightly look towards the future. The evidence seems to be mounting that this thing isn’t going to go away and, even if it did, we have learned enough to know that we need to be better prepared for the possibility of pandemics in the future. This point was well-articulated by Harvard epidemiologist Michael Mina in an interview with New York Magazine last week:

It’s all just been so sad to me, this unwillingness to look to the future and say, in the midst of all of what’s happening today, “What can we do to set us up for down the road?” To say, “Let’s not act like this is going to be done in a few weeks.” Let’s stop that ridiculous thinking and say, “What do we need to do today to set us up for one year from today, so that one year from today we’re looking back and we’re saying, Thank you, prior self, I’m happy you did that.” But we have had zero of that. Just the development of the vaccine. But even there, we took a very narrow view and didn’t really future-proof it.

Right now is always the best time to do these things, to get ourselves prepared for the future. And, you know what, if we spend a billion dollars and we don’t need it for this pandemic? Great, that’s great news. A billion dollars is nothing for a $16 trillion virus. But you know what, the more likely scenario is that we will end up using it.

Why is this interesting?

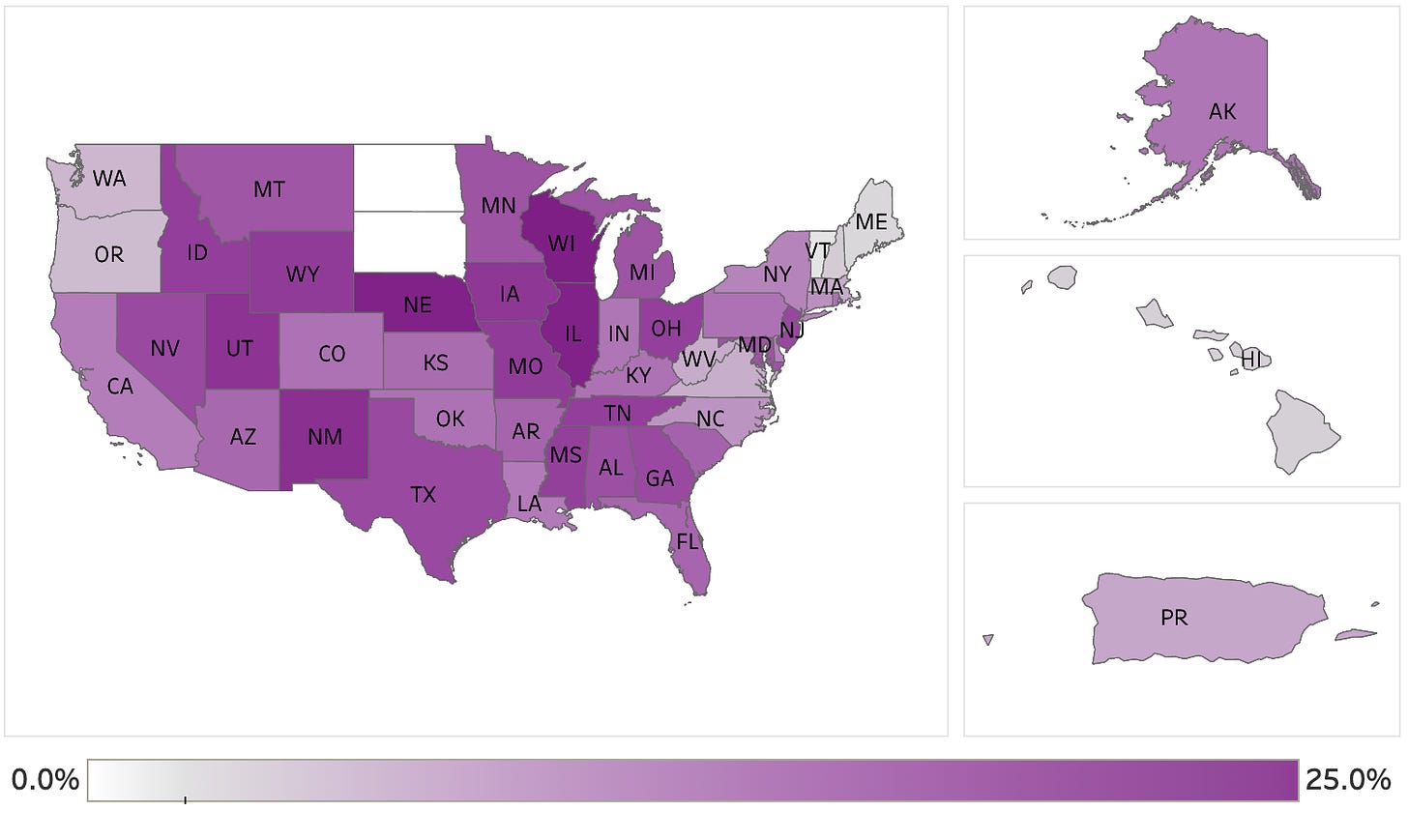

Mina doesn’t just ask the question, but he offers an answer and it ties back to one of the pieces of research from the fall that caught my eye the most. Back in November, a study came out that attempted to answer what portion of the population had already had COVID. While that question has produced lots of answers over the last year, the way this study went about researching the question fascinated me: they took extra blood from commercial laboratories and checked it for COVID antibodies. From the paper:

Laboratory A collected specimens from 7 jurisdictions (Arizona, Indiana, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia), and laboratory B, which was involved in an earlier CDC-led seroprevalence survey, provided residual sera from the remaining 45 jurisdictions. Each performed chemiluminescent immunoassay testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and provided CDC with deidentified information on patient age, sex, state, and specimen collection date. The zip code of residence and ordering clinician zip code were also collected. For both laboratories, most specimens were collected in the outpatient setting, although individual-level data on the source of specimens were not available. Information on patient race/ethnicity and symptoms was also not available.

Critically, because all blood was de-identified, the study was “determined to be consistent with non–human participant research activity.” They checked with the CDC and were able to do this without informed consent. This is now part of an ongoing CDC survey of seroprevalence that offers a good hint for real levels of COVID seen across the country.

Mina wants to take this idea a step further to create “a global immunological observatory”:

There’s a few things that are constant across the whole globe. Two of them are, when people get sick they get blood tests, and people donate blood, Blood samples taken in pretty much every single town and city in the world. But the moment that the result the doctors wanted to get is done, they throw away the tubes of blood. Well, what if those tubes weren’t thrown away? What if they were all packaged up and sent to a government facility or franchised immunological observatory labs, and processed with a core set of immunological tools that would give you an understanding of all the pathogens people see. And it can all be de-identified, so it wouldn’t be traced back to individuals. It would turn us all into little weather buoys for infectious disease.

One of my many takeaways from the last year is that governments at all levels did a terrible job doing multiple things at once. While we were focused on lockdowns we failed to get testing figured out, when we focused on testing we took our eyes off vaccine rollout, and on and on. Now as vaccines seem to be rolling out much more effectively (with more coming soon), we are getting clearer guidance on masks and ventilation, and—fingers crossed—we’ll have rapid testing widely available in the near-to-mid future, it’s time to demand that our elected officials and related agencies push the time horizon further. This isn’t because we’ve accomplished our mission, but because we need our government to be able to walk and chew gum, and in this case walking is testing and vaccinating the public and chewing gum is ensuring we’re prepared for another wave in the fall. If we get things right in the months ahead, that wave could look like a tiny blip, and the better monitoring we put in place, the better we’ll be able to ensure that in the years ahead other blips don’t reach pandemic proportions. (NRB)

Gesture of the day:

If you’re enjoying WITI, share it with one friend by clicking the nice green button below. (CJN)

Quick Links:

It’s worth catching up with Apple’s app tracking transparency (ATT) if you haven’t. Here’s an interesting take on some possible unintended consequences: The profound, unintended consequence of ATT: content fortresses. (NRB)

Don't call it the 'British variant.' Use the correct name: B.1.1.7 (NRB)

Dependency Confusion: How I Hacked Into Apple, Microsoft and Dozens of Other Companies (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).