Cass Marketos (CS) is a digital & content strategist based between New York and Los Angeles who's worked across art, tech, and government.

Cass here. Over the last decade or so, efforts have been underway in Joshua Tree National Park to identify areas of the landscape that would prove most stable through extreme variations in weather patterns across the coming decades. The hope is that these zones, called “climate change refugia,” would provide stable havens for the park’s titular tree species—and, perhaps, save them from dying out altogether.

Why is this interesting?

Until relatively recently, “conservation” work, broadly speaking, meant restoring an area of land to some past ideal state. Areas once mined for resources and degraded into ecological dead zones could be recaptured by federal entities and deliberately re-engineered as the wetlands they once were, inviting back plant and animal species that had sometimes been decades absent. Coral reef “recovery programs” transplanted lab-grown corals onto wild reefs, returning them from the brink of overfished, nutrient-deprived death to flourishing life. These projects, and others like them, were focused on identifying an environment’s past peak ecological function and then turning back the clock with a series of technical interventions. However, as climate change becomes more and more of an irrefutable reality, we have a grim environmental fact to face: the way things used to be may no longer be applicable. We may no longer be able to go “back”—and, instead, will be forced to think ahead.

What does environmental conservation look like in a (quickly) changing climate? What plant and animal species might any given area be able to support in ten years? What about fifty? Projects like the one in Joshua Tree National Park, and the more general concept of “climate change refugia,” are just one approach to reckoning with this intimidating new reality. What can we save? What will have to change?

Right now, there is no clear consensus on an answer. Creating climate change refugia is becoming one increasingly popular approach, with projects to identify climatically-resilient zones springing up all across the United States. Some seek to save glacial lakes and spruce-fir forests, another one the entire Mojave Desert. Broadly, their goal is to create a “slow lane” for climate adaptation, giving plants and animals a second to catch up to shifting weather norms, and then expand back out into the surrounding territory, repopulating areas that would otherwise be devastated.

Land managers and forest service employees tasked with helping heavily burned areas recover are also tinkering with their own warming-aware strategies. They recognize that the forests burned down today are not likely to be the same forests that will thrive in a climatically changed future, and that reseeding requires careful calibration for species type and diversity in order to both fire-proof and future-proof an area. Take this example from foresters working to restore burned areas in Butte County, CA, a region historically populated by a mix of native pines and cedar:

The plan for the burned region, largely located at lower mountain elevations below 4,000 feet, will include a mix of measures: thinning and burning back shrubs to help [native] oaks naturally resprout; replanting some areas with a seed mixture with more hardwoods and fewer conifers than were there before; and sourcing seeds from lower elevations. It may be a bit of a gamble, but with climate change looming it may be riskier to just plant the same trees again, [Wolfy Rougle, a project coordinator] says. “We need to have the humility to try a few different things.”

Elsewhere, some are turning to genetic analysis—and even engineering:

Scientists are also using genetic analysis to understand on a more granular level which traits enable a tree to cope with future drought or heat. A gene variant might, for example, result in trees having more roots in proportion to shoots, which means they can draw more water while limiting moisture loss from leaves. Once they’ve identified individuals with traits like this, researchers can study saplings in test environments to see how well they do.

Huge challenges face these projects. Climate models are unpredictable because uncertainty looms about how effective (or far-reaching) carbon-reduction strategies will be. Species planted today that are meant to survive in warmer climates, may not germinate properly in our current, still-cooler temperatures. Trees in California, particularly, are highly specialized. A conifer seed that would germinate at 200 feet of elevation might lay permanently dormant just a few hundred feet higher.

Although each of these projects varies in their approach and methodologies, what they have in common is a distinct shift from the attitude of conservation efforts in the past. No longer is it a given that we can simply go back— “restore.” It seems that our only remaining option is to forge ahead. (CM)

Website of the day:

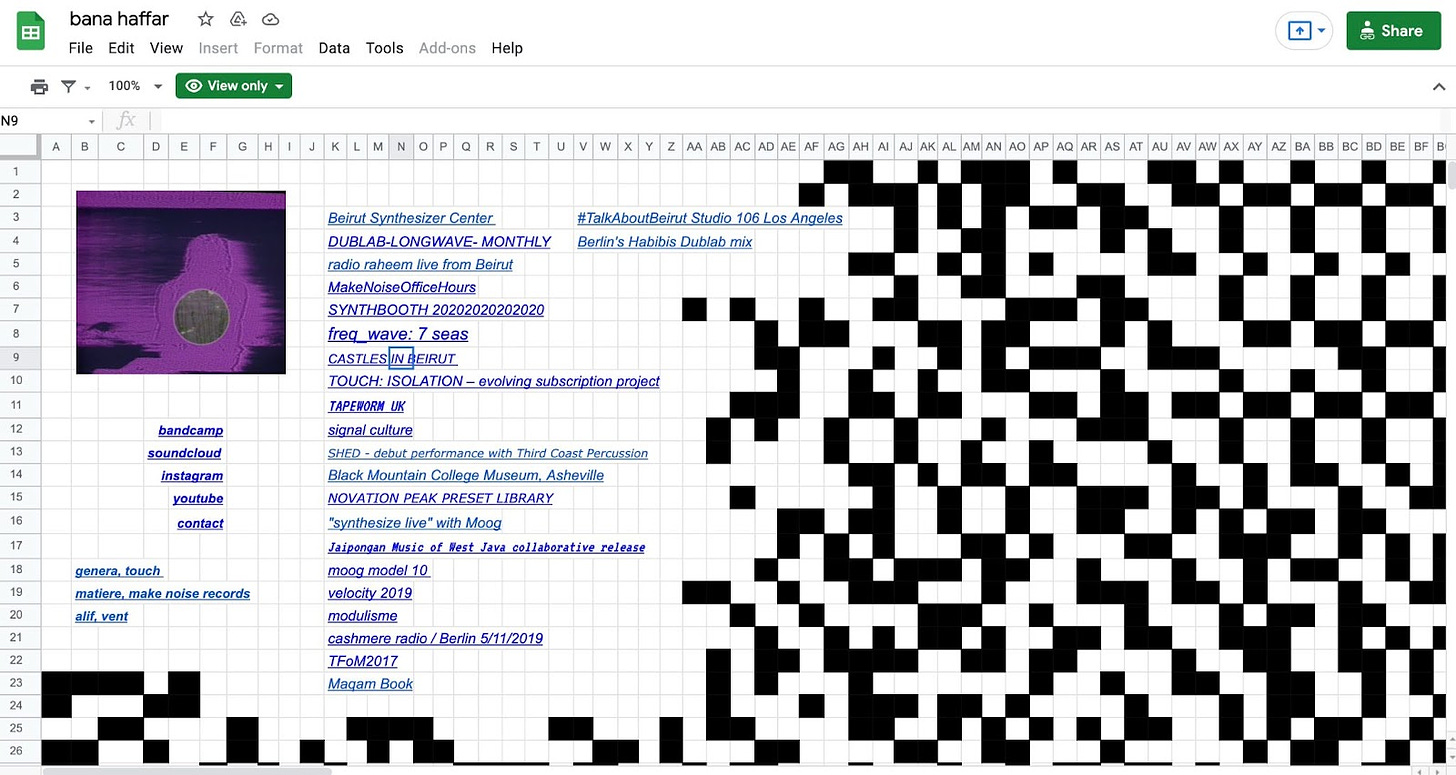

Electronic musician Bana Haffar is doing an MMD for us soon. Her website is great: A google sheets doc, with a twist! (CJN)

Quick Links:

--

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

The payments landscape. The payments world took an economic hit from the pandemic, just as others did. Indeed, in 2020, global payments revenues declined for the first time in 11 years. But today there’s reason for hope: the decline was smaller than anticipated, and indicators show a nominal rebound for 2021. The latest edition of McKinsey’s long-running global payments report helps to unpack the industry’s dynamics overall and looks closer at topics such as digital currency, transaction banking, and new revenue models. Check it out.

--

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Cass (CM)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.

Link to Bana Haffar doesn't work. Looks like it's https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1JJGQv7dsmmwGjEA5U8iXq-eIG4Jab85KbSs55vsf7U8/htmlview