Jason Boog (JB) is the editorial lead at Fable, the social app for readers. He is also the author of The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today, and contributor of The Euchre Edition and the ECM Sound Edition for WITI.

Jason here. Nearly 60 years ago, the exiled Guatemalan author Augusto Monterroso wrote a glowing introduction to the work of a provincial intellectual named Eduardo Torres in the literary journal Revista de Bellas Artes. Monterroso had been charged with curating Torres’ archive, a project funded by the Endymion Journal and Publishing House headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. While exploring the archive, Monterroso had discovered Torres’ translation of Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” and convinced the literary journal to publish the work. Comparing Eduardo Torres to Aldous Huxley and George Orwell, Monterroso promised to edit a collection that would finally introduce this “great master of San Blas” to a global audience. Over the next few decades, more work by Eduardo Torres sporadically appeared in literary journals, and Monterroso mentioned him during interviews, but the translator’s literary moment never seemed to arrive.

Then, in 1978, Monterroso published a satirical novel called The Rest Is Silence, collecting interviews, portraits, aphorisms, essays, and translations, all attributed to a fictional character named Eduardo Torrres.

Why is this interesting?

At this point, readers realized that the Mexican translator had never existed.

Monterroso had invented the Endymion Journal and Publishing House, and done the translating work he had attributed to Torres himself. For more than 19 years, Monterroso had cultivated Torres as a literary heteronym—an obscure literary term for an authorial persona that takes a life separate from its creator, publishing essays, poetry, or even books in the real world. Earlier this week, NYRB Classics published a translation of The Rest Is Silence, reintroducing readers to the art of heteronym.

Oddly enough, Monterroso never really admitted that Torres didn’t exist, making winking references to his literary secret identity until he died in 2003. The Rest Is Silence includes a review of one of Monterroso’s own novels, supposedly published by Torres in his local newspaper. In the essay, the heteronym compared his creator to an ant “struggling mightily to carry a load much larger than it can handle.” Torres ended the review by snickering at the modest size of his creator’s literary output: “Let each, then, bear the burden that his strength permits.”

The brilliant and obsessive Portuguese author Fernando Pessoa coined the term “heteronym” for this feat of literary illusion. When Pessoa died in 1935, he left behind an enormous trunk full of writings that scholars have spent decades exploring. He wrote everything from detective stories to poetry under various heteronyms, but his masterpiece was The Book of Disquiet, a sprawling collection of fragmentary prose attributed to different personas with individual biographies, beliefs, and writing styles – scholars have counted more than 100 different imaginary writers in included the Pessoa Extended Universe. “They are beings with a sort-of-life-of-their-own, with feelings I do not have, and opinions I do not accept,” Pessoa wrote when describing his beloved heteronyms. “While their writings are not mine, they do also happen to be mine.”

These days, most of us scatter digital heteronyms everywhere. I’ve written reams of bad science fiction under a certain Reddit username, and I’m sure many other writers nurture similar secret identities. Someday, literary archaeologists will comb through digital attics, looking for clues to the online personas inhabited by authors. And getting old means leaving heteronym versions of your self behind: the “Jason Boog” writing these paragraphs is a vastly different person from the version of me who wrote “Born Reading: Bringing Up Bookworms in a Digital Age” during the Obama administration. Strange and fragmented manuscripts like The Rest is Silence and The Book of Disquiet show us how to make room for all the voices that live inside of us.

Noah here. I’m putting my BRXND Marketing X AI event in LA on February 6, 2025. Tickets are currently $550 for early-bird buyers. If you’re a marketer, you should come. If you know a marketer on the West Coast, you should send this their way. Get your tickets now.

If you have any questions, please be in touch.

Bonus: Untranslatable Poem of the Day

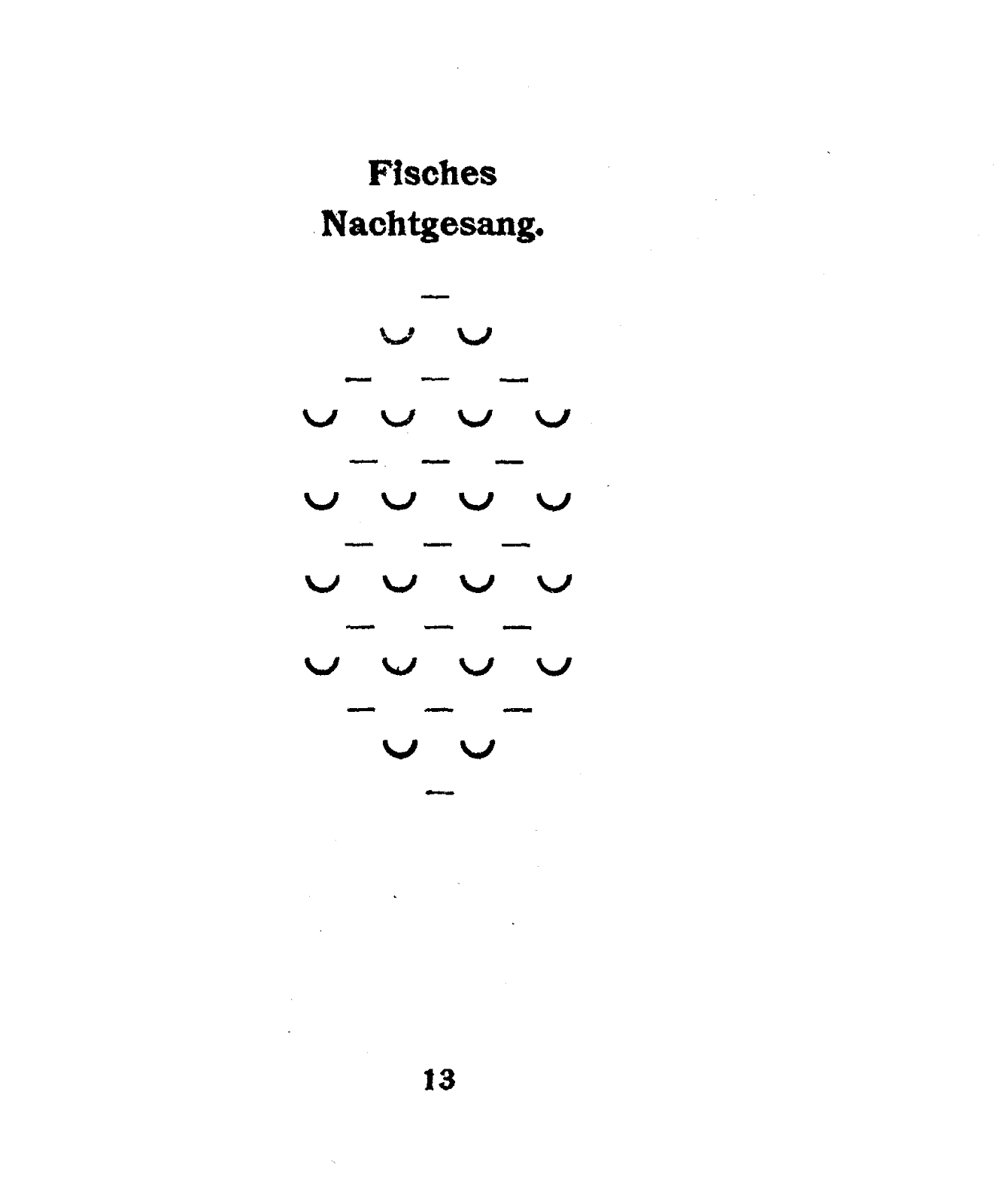

For two hilarious pages in The Rest Is Silence, Monterro's heteronymic author struggles to translate “Fisches Nachtgesang” (“A Fish’s Nocturne”), an experimental work by the German poet Christian Morgenstern. First published in 1905, the poem consists of two repeated diacritic symbols (meant to denote meter in Greek and Latin poetry) that make the shimmering shape of a fish. I found the original at Project Gutenberg.

Quick Links:

Try the SocialAI app where you are the only human participant at the center of a bustling social network. All of your followers are bots, and you can pick and choose what kind of readers you want. Inside this AI-driven echo chamber, Supporters, Counselors, and Visionaries will argue endlessly with Doomers, Skeptics, and Sarcastic People about every word you post. It’s a vertiginous glimpse into how AI-generated heteronyms will fill (or probably already fill) our social media feeds. (JB)

I got obsessed with Evan Ratliff’s Shell Game podcast earlier this year, listening as he made an AI voice-clone to explore existential crises and AI anxieties. My son and I spent hours playing with the tools Ratliff used in his reporting, and I was blown away by the scary rate of evolution in voice AI.

Netflix just released an adaptation of Pedro Paramo, a completely unclassifiable novel by Augusto Monterroso’s longtime friend, Juan Rulfo. Once you read this singular book, even the best adaptation will feel superfluous. It’s like James Joyce and Franz Kafka collaborated on a spooky Western. (JB)

One of my favorite users of heteronyms was Philip Jose Farmer. Most famously writing Venus on the Halfshell under the pen name Kilgore Trout, a character from Kurt Vonnegut.