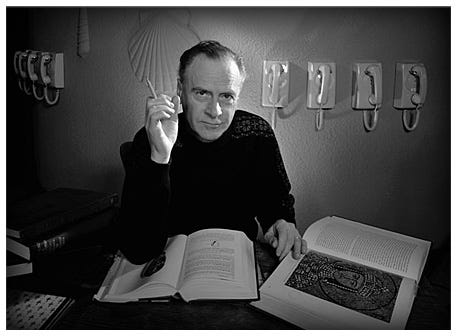

Noah here. As has been well-documented at this point, I’m a big McLuhan fan. I find myself turning to his writing and thinking when I need to get out of an intellectual rut. Recently, I re-read parts of his 1969 Playboy interview and was struck by his response to a question about whether he thought we were turning too much of our future agency over to technology.

First of all—and I’m sorry to have to repeat this disclaimer——I’m not advocating anything; I’m merely probing and predicting trends. Even if I opposed them or thought them disastrous, I couldn’t stop them, so why waste my time lamenting? As Carlyle said of author Margaret Fuller after she remarked, “I accept the Universe”: “She’d better.” I see no possibility of a worldwide Luddite rebellion that will smash all machinery to bits, so we might as well sit back and see what is happening and what will happen to us in a cybernetic world. Resenting a new technology will not halt its progress.

Why is this interesting?

First off, it’s always fun to read McLuhan explaining his style as probing. It’s long been my belief that part of why he’s so hard to read/listen to is he was just screwing around with people and the medium. Probing them. It doesn’t necessarily make it any easier to get through, but at least it offers a bit of context.

Second, it’s interesting to see McLuhan push back against the idea that he was a booster of technology just because he wrote so much about it. This is obviously something we’ve seen pop up over the last decade. What I didn’t realize about McLuhan, however, was how concerned he really was about the impact of technology on society. Here’s a bit from Douglas Coupland’s out-of-print biography of McLuhan:

The late 1950s were probably the most intellectually electric period of Marshall’s life. New ideas crackled around his head like Tesla waves. Society was absorbing too much technology too quickly, and he knew it. Did he like this? No! He hated, loathed, abhorred it. There was a small window in the late 1950s when he had a drop of hope that the world might become a better place with new technology—but that hope quickly died with the decade. As of the 1960s, Marshall viewed the mortal world as a lost cause because of both pollution and technology, and he pined for another era, a different time stream, a different universe—anything different from booming North America’s guns- and-butter praxis. How the man ever came to be perceived as technology’s cheerleader is a mystery. Not that any of this stopped McLuhan on his quest for ideas.

McLuhan was super religious, and the argument Coupland lays out, which jibes pretty well with that Playboy quote, is that he stuffed all those feelings inside him in order to explore (probe) the world of media more effectively. Part of what makes him so readable today is that his books aren’t full of predictions that never came true or strongly worded moral warnings about the downfall of society. On one hand, you can read a lot of what he said as vague enough to be true at any time. But that’s not how I (and lots of others) see it. Rather, to me, he’s still relevant because he was looking at these concepts—media, communication, technology—in their purest sense. (NRB)

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.

What Coupland unfortunately misses there -- and I enjoyed and appreciated his McLuhan book quite a bit -- is the hope which did not die in the 50s but is consistent in his work up to and beyond the Playboy piece. Here's another passage from that excellent Playboy piece, which covers a lot of territory: his sense of hope and feeling that we're far from helpless or 'technological determinism', as well as the two-fold nature of technology's effects on us, the 'psychic (elsewhere 'personal') and the social':

"There are grounds for both optimism and pessimism. The extensions of man's consciousness induced by the electric media could conceivably usher in the millennium. But it also holds the potential for realizing the Anti·Christ -- Yeats' rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouching toward Bethlehem to be born. Cataclysmic environmental changes such as these are, in and of themselves, morally neutral; it is how we percieve them and react to them that will determine their ultimate psychic and social consequences. If we refuse to see them at all, we will become their servants. It is inevitable that the world-pool of electronic information movement will toss us all about like corks on a stormy sea, but if we keep our cool during the descent into the maelstrom, studying the process as it happens to us and what we can do about it, we can come through.

Personally. I have a great faith in the resiliency and adaptability of man, and I tend to look to our tomorrows with a surge of excitement and hope. I feel that we're standing on the threshold of a liberating and exhilarating- world in which the human tribe can become truly one family and man's consciousness can be freed from the shackles of mechanical culture and enabled to to roam the cosmos. I have a deep and abiding belief in man's potential to grow and learn, to plumb the depths of his own being and to learn the secret songs that orchestrate the universe.We live in a transitional era of profound pain and tragic identity quest. but the agony of our age is the labor pain of rebirth."

Thanks for the interesting note, Noah and Colin.

All the more reason for EVERYBODY to read/digest every chapter of 1964 Understanding Media... and also subscribe to the McLuhan Institute susbtack.