If you like what we do every day, consider subscribing for 7USD/month. You’ll also get a weekend edition that is completely different (and awesome). -Colin and Noah

Scott Stedman (SS) is an entrepreneur who co-founded Northside Media Group, TOURISTS, and Saturnalia. He came of age living on a bookshelf in Paris, where he was named a person of interest in a murder on the Seine, and has been trying to make sense of mystery, and all the other things he’s read ever since.

Scott here. We’re here today to talk murder… well, the genre.

Edgar Allan Poe invented the murder mystery genre we know today with C. Auguste Dupin, a purveyor of “ratiocination,” or intensive reasoning—who was introduced to the world in The Murders on the Rue Morgue. Since then, we’ve collectively engaged in a 150-year love affair with the cat and mouse of murder mysteries. We’re reminded of how much we delight in the genre when a specific story captivates our collective imagination: Gosford Park, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Knives Out. The latter was such a phenomenal success that Netflix recently paid Daniel Craig $100,000,000 to reprise the role in two upcoming films.

Why this is interesting?

When I described murder mysteries in that second sentence, your mind likely jumped to two authors: Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie. While Poe may have invented the genre, Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes did something that the form had never seen—they changed “reason” into “science” and applied it to the art of deduction. Holmes was introduced in the novella, A Study in Scarlet, published in 1887, the same year as the Michelson–Morley experiment, the first step toward Einstein’s theory of relativity. Thus began a long dance between the murder mystery’s evolution and the shifting anxieties of people caroming into modernity.

While Doyle spurred an entire literature of copycats (most interestingly, the Holmes-eque villain Fantomas, who since his introduction in 1911, had an unlikely second life as a French film franchise widely celebrated in the Soviet Union). It wasn’t until Agatha Christie introduced the world to Poirot that the genre shifted into its strictest and most enduring form: the garden variety murder mystery.

“I specialize in murders of quiet, domestic interest.” – Agatha Christie.

Agatha Christie is the most popular modern writer to ever live (outmatched in sales by only Shakespeare and the Bible). Christie is unrelenting in her ability to surprise—she killed children, popularized the unreliable narrator, introduced serial killers. Still, she was a fiercely disciplined adherent to a form created by her community of fellow writers, developed in the legendary Detection Club (including Dorothy Sayers, Ronald Knox, and the remarkable GK Chesterton). In an age sandwiched between two world wars—her stories brim with pride for a stiff British moral certitude that was impervious to the most heinous acts against it. The form these stories were built on follows a similarly strict set of rules codified into a famous list known as Knox’s Decalogue:

The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.

All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

No racial stereotypes. (Scott’s Note: I’ve slightly adapted the language from the original which now reads as very dated and racist when the intention was the opposite).

No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition that proves to be right.

The detective himself must not commit the crime.

The detective is bound to declare any clues which he may discover.

The "sidekick" of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal from the reader any thoughts which pass through his mind: his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

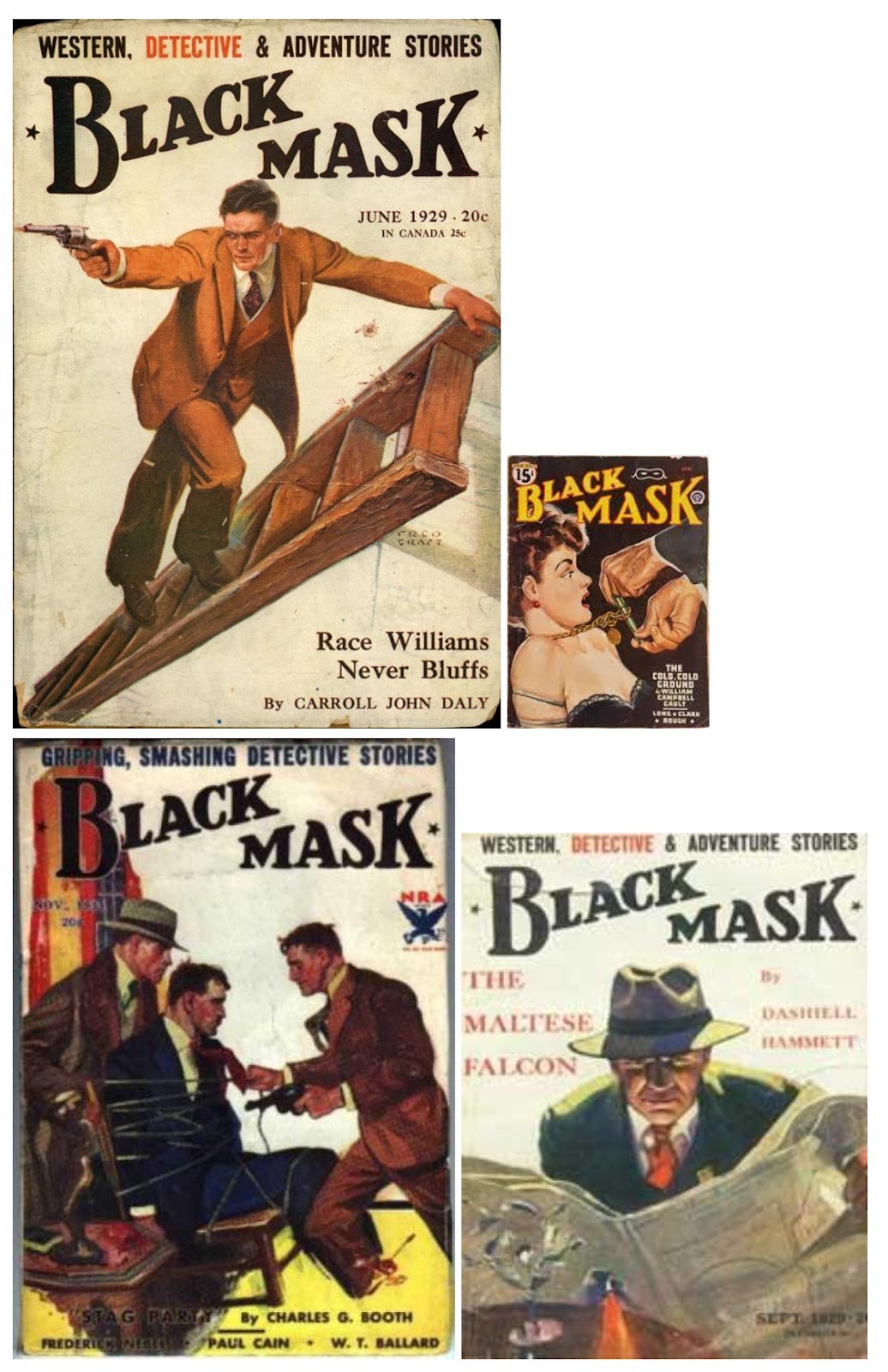

Dame Agatha and the Detection Club’s rules ushered in what’s known as the Golden Age of detective fiction. However, on the other side of the pond, a revolution in form was brewing in the livers of Dashiell Hammett and his successor Raymond Chandler. Hardboiled cop fiction took all Agatha Christie’s rules and blew them straight to hell.

Hardboiled detective stories were the exact opposite of the garden variety created in England. Detectives like Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe didn’t adhere to the genteel community guidelines of Inspector Poirot, Ms. Marple, or Lord Peter Wimsey. They didn’t give a damn what people thought. They followed their own existential code, with similar rigor, regardless of the consequences.

The last great innovation to transform the genre began with Lawrence Treat’s unsuccessful book V as in Victim. A decade later the police procedural would grow in popularity and attain global recognition with the rise of writers like the husband and wife team of Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, whose 1965 novel Roseanna remains a classic of the genre.

The police procedural anchors the detective in clearly defined routines of real life. There’s no quart of scotch before work without implications. There’s usually a family not far away. Clients aren’t bombshells. And there’s lots of paperwork. While the procedural carries lots of aesthetic and structural similarities with both previous forms (the garden variety and hardboiled), there is one difference that’s most notable: The villain is at a notable disadvantage. The cop is the pro—and he’s got the resources of the police department behind him. This is not a clash of superheroes, but a reflection of what most readers are hoping to do in their own lives: finding the exceptional in the banal. Of course, the great procedural writers like Henning Mankell use the significant structural constraints to great effect, and those few moments when a detective truly transcends the mundane are glorious.

The murder mystery is a genre that’s so rich and surprising to its readers because it marries form and purpose effortlessly—the rules and aesthetic guidelines of each genre, reflect the unique moment in time that the writers were living through. The garden variety murder mystery mirrors a centuries-old British culture torn by war, watching its traditions melt into modernity. While hardboiled was born from a new American culture defining itself without a unifying identity. Finally, the procedural tears down the mythologies of the genre, instead portraying the classic battle of chaos vs. order, as a mundane slog through a working-class 9 to 5—a fight that many could identify with as automation and globalization began to de-personalize the modern workforce.

The constant play between the aesthetic and cultural—illustrated both by each genre’s unique form, and the history of how that form emerged—gives the murder mystery’s greatest storytellers an incredible array of tools to subvert, divert, suspend, expound, and confound. With our culture changing under our feet, it’s quite certain that there will be new approaches to the murder mystery that will keep us engaged everywhere from the beach to the bedroom—with only one thing for sure… someone’s gunna die, and someone’s gunna figure out whodunit. (SS)

[Sponsored links: Atlas Bars are GMO-free and keto-friendly with 15 grams of protein and just a gram of sugar. We’ve tried Atlas and they are very good. Use this link for WITI readers to get 20 percent off. Get started with the sample pack.]

__

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

Combating the Great Resignation. To keep top talent in the fold, managers must actively change their leadership styles—focusing less on controls and more on culture and connections. A recent episode of The McKinsey Podcast explains how to respond and adapt.

--

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Scott (SS)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).

Agatha Christie broke rule #9 in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

Also, for those of you that love novels by Josephine Tey and Dorothy Sayers, you should add Ngaio Marsh to your list. I don't know why she's rarely mentioned, but she wrote many wonderful detective novels. She started writing in the mid 30s and her last novel was published in 1980. Her first few novels were good (not great) but after just the first few, she was a consummate writer.

Honestly curious—what do you think he meant by the "No Chinamen" rule, if you believe he didn't intend to be racist? Thanks for a great article!