Eurof Uppington (EU) used to run hedge fund money until he came to his senses. Now he worries about how we eat and sells olive oil from family farmers in Greece to restaurants in Switzerland and France. He has previously written about olive oil (twice) and the future of meat.

Eurof here. The job of modern agriculture, as Michael Pollan famously noted, is to turn fossil fuels into edible calories for humans. There are many steps by which crude oil becomes a salad, a hamburger, a soft drink, or a chicken (or alt-chicken) nugget, but it all started in 1909 with Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. The pair invented and commercialized a process to create ammonia and thereby nitrogen fertilizer and explosives from natural gas, naphtha, and coal—at scale.

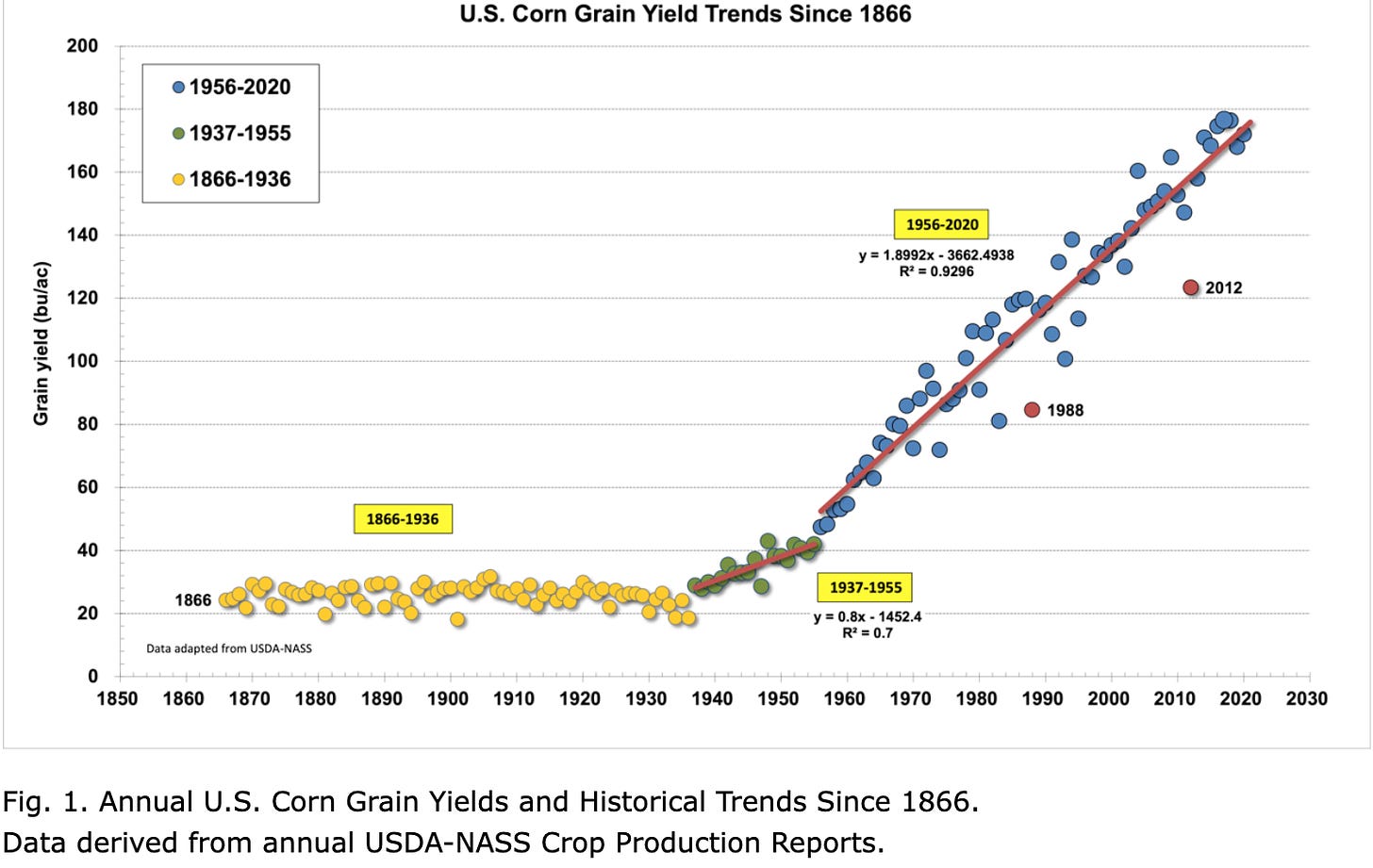

The Haber-Bosch process is foundational to our food system, post-war population growth, and much of the modern world. Together with pesticides, farm automation, and GMOs, nitrogen fertilizer is a key factor behind the lesser-known “Moore’s Law” of food: US corn yields have grown a steady 2 bushels/acre every year since the 1950s.

Nitrogen is the key factor in promoting plant growth. The relationship between food calories and fossil fuel is incredibly direct. Half a gallon of crude makes a bushel of corn or 5,600 Tostito corn chips, or high fructose corn syrup for 410 cans of Coca-Cola. All made from dead dinosaurs.

So yes, the food system is addicted to nitrogen. And we’re about to go cold turkey.

Why is this interesting?

Energy prices and thereby cost pressure in agricultural inputs were sky high before the invasion of Ukraine. With the war, the sudden disruption to grain production, together with rising gas prices, have increased pressure to levels where key commodity prices are going haywire, with mostly bad 1st- and 2nd-order consequences.

Short-term disruptions are already unavoidable. Food price inflation in key ingredients will accelerate, with all that that involves for countries with underdeveloped welfare states. Specifically, Ukraine and Russia provide 60% of the world’s sunflower oil and 30% of global wheat exports. Prices for both are at decade highs. Even if mass starvation should be avoided, the disruption of food supplies in politically unstable countries can have important results. Remember the Arab Spring? That was preceded by 20% spikes in food inflation across the Middle East, which is particularly dependent on wheat. Egyptian analysts are worried all over again.

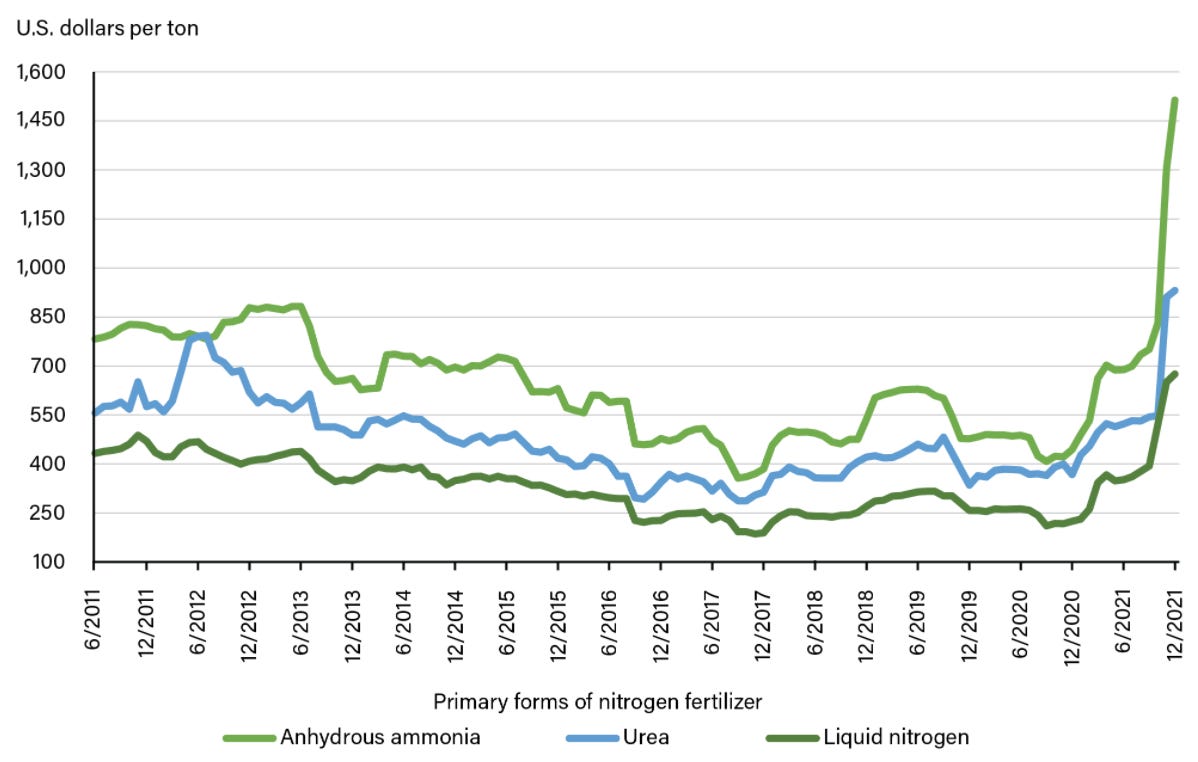

But the 2nd order, long-term consequences of permanently higher natural gas prices may be more meaningful. Methane, natural gas, is today the key input of the Haber-Bosch process. At the beginning of 2021, the price of Iowa ammonia—a form of nitrogen fertilizer—was already 3x costlier than it was twelve months earlier. We don’t know where the price will eventually go (except up), but the factories have already started to shut down. They’ll reopen only when the price of fertilizer has risen to cover the rapidly rising price of gas.

Cheap fertilizer=cheap food. Nitrogen fertilizer created inexpensive corn and soy, the anchor crops of our food system. According to NYU, highly processed calories provide almost 60% of all calories in the typical US diet. In these foods, corn- and soy-based ingredients feature prominently as sweeteners, thickeners, fats, and overall dry weight. US meat production is even more corn and soy-dependent. 95% of beef is “grain-finished” in giant feedlots. Europe may be less affected as more calories come from more heterogenous whole foods, but even there, the percentage of household income spent on food has plummeted in the last 50 years. This is likely to reverse.

So the main 2nd order consequence is going to be generalized disruption. For food companies with weak market power, unable to pass on rising costs, this is going to be a problem. Our main concern, however, should be for food-insecure families on the edge of poverty.

The main glimmer of hope from the fertilizer crisis is environmental. We all understand that the Ukraine crisis is going to lead to renewed efforts to decarbonize energy and transport, to wean ourselves from fossil fuels. Fertilizer is a direct contributor to global warming in many ways, most notably because much of it evaporates as NO2. There’s a huge set of farming techniques to regenerate soil that developed world farmers have simply stopped using, like composting, cover crops, rotations, and mixed farming combining arable and livestock. Cheap fertilizer did away with the need for all that. WIthout cheap gas, we’re going to have to rely much more on natural means to create soil fertility. With that should come improved nutrient density, tastier food, and, above all, massive carbon sequestration in soil.

Maybe that’s the 3rd order consequence of this coming crisis, and I’m hopeful. The end of the era of fossil-fueled nitrogen dominance might mean a new golden age of food! We just have to get through some pretty terrible stuff first. (EU)

--

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

Tech trends for 2022. What technology trends are top of mind for business? We asked leaders in industry, academia, and at McKinsey to share their perspectives on what’s likely to headline business agendas this year, trends that could—but shouldn’t—slip through the cracks, and what executives should think about when considering new technologies. Here’s what they told us.

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Eurof (EU)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).

The piece does not suggest that alternative means of fertilizing could maintain the positive trend line of efficient crop production, which is essential. Fortunately, the U.S. is a world leader in natural gas resources. We need to boost our domestic natural gas production to meet the market demand.