Eliz Mizon is a UK-based writer, media reform activist, and documentary nerd. We are pleased to have her first WITI contribution today. -Colin (CJN)

Eliz here. Can documentaries change the world? This question was posed by film theorist Jane Gaines in a 1999 essay in which she explored whether “images of struggle” could convince audiences to struggle in kind. If comedies can elicit a laugh from the body, and pornography can elicit… arousal, can propaganda, activist documentary, or raw footage of a riot encourage people to get off the couch, or out of the theater, and rise up?

In my research (which I turned into a short video essay) I found some seemingly very clear instances of documentaries changing the world: less than a year after Making a Murderer was released, a US magistrate determined Brendan Dassey’s confession was obtained unlawfully and ordered his release. A month after Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich was released, Ghislaine Maxwell was arrested by the FBI. A month after The Social Dilemma was released, CNBC reported a wave of users deleting their social accounts, and the world saw the CEOs of Google, Twitter, and Facebook grilled in another Senate hearing.

None of these films exist in a vacuum, however. Brendan Dassey, whose appeal had been in motion since well before Making a Murderer aired, had his conviction upheld. Ghislaine Maxwell was being investigated by the FBI before the Epstein documentary, and the CNBC article about The Social Dilemma included as much discussion about users using social media to talk about the film, as it did about users deleting their accounts.

Why is this interesting?

Perhaps the most well-known documentary to produce concrete change was Blackfish, about the mistreatment of orcas at SeaWorld. The film even coined a new phrase: “The Blackfish Effect.” After the film’s release in 2013, SeaWorld's income declined by 84%, Southwest Airlines ended their 25-year business partnership, and their stock price plummeted. When the company sought to deny that they had lost money, the US government brought fraud claims against them.

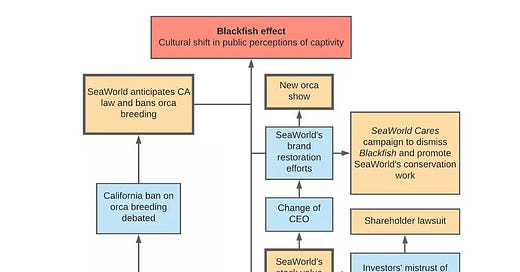

As in these other cases, there were other things happening in Sea World’s universe, but the causal chain appears pretty direct in this case, as visualized by researcher Laura Thomas-Walters:

The public has a short memory, though, and SeaWorld’s stock price would recover a few years later. But the company drew a permanent line in the sand when, in 2016, they announced that “this would be the last generation of orcas in SeaWorld’s care.” The company stopped breeding Orcas that year.

So a perhaps small, yet significant, concrete change there. But is the documentary to change pipeline always so direct?

Documentaries exist alongside and within current social movements and global conversations. They can become huge talking points that, in the viral information age, are often conducted on a massive scale across the globe (The Social Dilemma has been seen by more than 38 million people).

But documentaries are a form of entertainment, no matter how much awareness-raising they can do. As we’ve seen in crisis after crisis, it takes a plethora of committed actors to make any significant movement and create lasting change.

In the case of Blackfish, the filmmakers were able to marry an ecosystem of growing action and outrage with their skill for telling a deeply affecting story, delivering a final nudge of awareness that convinced many people holding power—legislators, executives, and shareholders—to take a stand against animal abuse.

When filmmakers contribute to an existing movement and choose the right moment to ride an existing wave of public pressure, action, and will, they too might be able to change the world. (EKM)

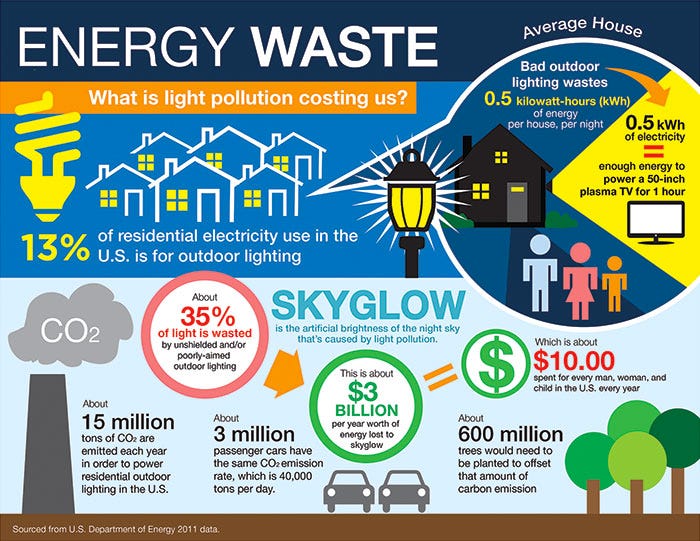

[Credit: International Dark-Sky Association]

Billion-Dollar Energy Saving Tip of the Day:

In the United States, light pollution costs more than $3.3 billion, and releases 21 million tons of carbon dioxide, per year (yes, that’s just the light being wasted, because of lights positioned at the wrong angle). Campaigners have been trying for decades to get manufacturers to create lights that produce less glare, and regulation to ensure lights are positioned to shine only where needed (not turned off). Americans could be making adjustments, still have all the light they need, and save $3 billion and millions of tons of CO2 every year. (EKM)

Quick Links:

If you’ve never seen the cult web series Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared, a kids-show-cum-Lynchian-nightmare, you simply must. A second series is tipped to be released this year, more than a decade after the original. (EKM)

A history of the old Intercontinental in Kinshasa (CJN)

Johnny Greenwood’s reaction is priceless (CJN)

—

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

Whose health concerns have we been solving for? Health inequities manifest in a variety of ways: limited access to food, care, or medication; unmet needs, when innovation is misaligned with disease burdens; or underserved communities when key actors fail to engage groups commensurate with their needs. Addressing the issues has obvious benefits for patients—and the pharmaceutical and life sciences companies that serve them. A new article outlines a framework to approach health equity.

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Eliz Mizon (EKM)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).