Kevin Maguire (KM) writes the New Fatherhood.

Kevin here. I spent the first few weeks of 2023 in Mumbai, India’s vibrant and bustling metropolis and glorious cultural melting pot. One of the five most populated cities in the world, home to over 22 million Mumbaikars, and predicted to grow by another 50% over the next 10 years. To say the city is overcrowded is an understatement—the city has grown at an explosive rate, and the infrastructure has been unable to keep up.

The city is covered in evidence of upgrades, with new metro lines forming above and below the city streets. But whilst they wait for public transport to catch up, the three-wheeled auto-rickshaw remains the quintessential transport experience of the city. They’re fast, fierce and fantastic value for money, with most rides under 2 miles costing less than 25¢.

They’re the city's lifeblood, responsible for ferrying its inhabitants between work, home, and the many fantastic places to eat and drink here. Like in any major city, you can use an application to book a ride, but it’s always more convenient to stand by the side of the road and hail one down, in a matter of seconds, with the familiar shout of “AUTO!” you’ll hear almost everywhere.

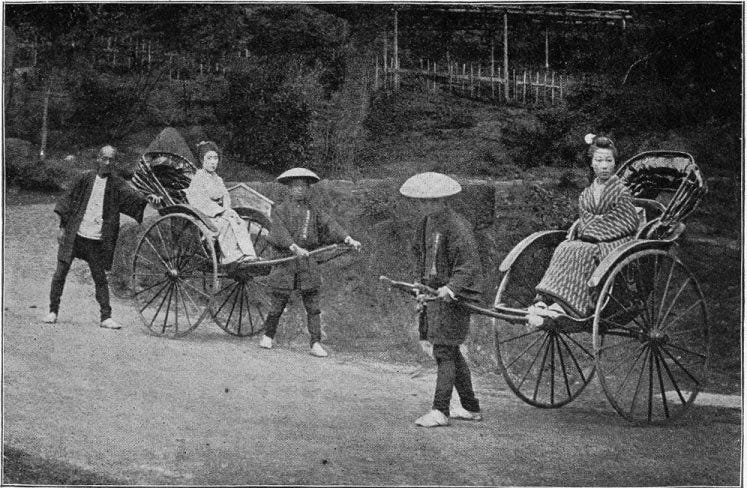

If you’ve spent any time in Asia you’ll be familiar with the rickshaw, but you may know it under one of its many other guises: by it’s onomatopoeic moniker “tuk-tuk” in Sri Lanka, “keke” on the streets of Lagos, Nigeria, The rickshaw has a long history—originally two wheeled, and 100% human powered, with one “driver” carrying one passenger, later upgraded with a third wheel and an engine. These gas-powered alternatives first appeared in Japan in 1931, and quickly spread across Southeast Asia, arriving in India in 1959.

The OG rickshaw. Batteries sold separately.

Why is this interesting?

Locals point to sometime in the late 1970s as the moment when the proliferation of auto-rickshaws became predestined. Rahul Bajaj, Founder and Chairman Emeritus of the Bajaj Group, convinced the Maharashtra government the auto-rickshaw was the perfect solution to their growing population problems— only 9 million residents at the time—and the lack of suitable transportation infrastructure. The government approved their expansion, and the city was transformed as a result.

No one knows exactly how many rickshaws are here in the city, and the number varies wildly. A 2019 report said there were around 125,000, but a year later they said the number was closer to 200,000, or 1 rickshaw for every 5 commuters, with around 75 million auto-rickshaws in operation across India. Riding through Mumbai on a rickshaw is an experience you won’t forget in a hurry—the rules of the road are different here, with the impetus on crash avoidance everyone else’s problem. The constant sound of horns blaring will be one of the first things you notice, as drivers tend not to rely on such novel inventions as wing mirrors here. You honk to make your presence known to other drivers, to let them triangulate your location akin to how dolphins whistle, or bats use echolocation (Noah went into more depth on this in The Car Horn Edition in 2020.)

Those used to driving in less chaotic cities will need time to get used to the rhythm of Mumbai’s roads. An auto-rickshaw driver will be adept at finding any gap to drive into, working his way through a busy cross section like a reenactment of Frogger (or an certain roundabout scene in an action movie currently running theatres—if you’ve seen it, you’ll know the one I’m talking about) as you spot a gap and make your way into it, assuming other cars will choose to slow down rather than plow into your side. You make your turn, or pull out into the main current, whilst trusting—no, hoping—they will slow down. At first, every turn feels like a potential T-bone collision. After a while, you get used to it.

Criticisms of the vehicles have been rising in recent years. Their issues focus on two key areas—safety and pollution. Auto-rickshaws come with no seatbelts, airbags, or any of the modern safety trappings we’ve come to expect from the vehicles we ride in. In normal circumstances this might not be something to worry about—one thinks of the lack of helmets seen on cyclists in Copenhagen, who are safely protected in their dedicated lanes—but coupled with the, let’s say, “innovative driving techniques” the auto-rickshaw drivers take here creates a cause for concern. An additional issue has been around the harassment, mistreatment and assault of women riding at night—a problem so rampant that the Government of India launched a pink rickshaw scheme in 2013, containing panic buttons and GPS tracking systems, driven by women, and with local districts providing financial incentives and favorable loan conditions to enable more women to purchase them.

Pink rickshaw image. Credit Indian Express

Air pollution in Mumbai is an increasingly serious problem, causing health concerns for residents and drivers alike, with auto-rickshaws contributing a large portion of the emissions due to their reliance on compressed natural gas (CNG). The government has begun a carrot and stick approach to spur a switch to electric rickshaws, mandating the eventual switchover, and incentivizing their purchase with loan access for those who wish to buy them. So far, these schemes have had limited success, as drivers see it as an added cost and inconvenience.

But despite their problems, rickshaws are undoubtedly a part of the glorious cacophony of Mumbai. It will be curious to see if, and how, they evolve to keep up with the demands of this incredible city. (KM)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Kevin (KM)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.

Good read. Thank you!

I also noticed a sticker on many rickshaws in Delhi that simply read "This Driver Respects Women." You gotta wonder about the drivers that choose not to sport the sticker.