An archive favorite today. See you tomorrow for some Friday Selects. -Colin (CJN)

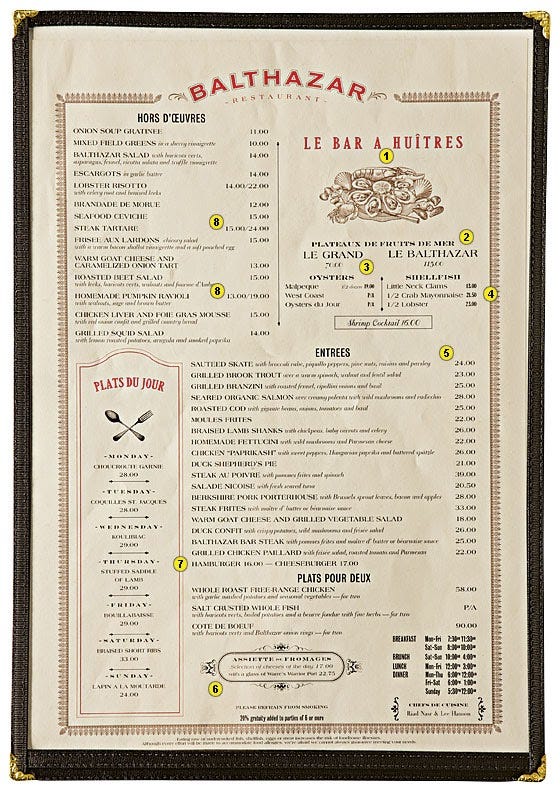

Colin here. I’m fascinated with the hidden alchemy that goes into making restaurants work. There’s obviously the stuff we see as customers: the light, the design, the greeting upon arrival, but then there’s a lot underneath the iceberg. We’ve talked in the past about the infamous Balthazar menu design, which cleverly uses psychology to nudge customers toward the more profitable items. In a New York magazine piece, they broke down all the sections, notably the upper right corner:

That’s the prime spot where diners’ eyes automatically go first. Balthazar uses it to highlight a tasteful, expensive pile of seafood. Generally, pictures of food are powerful motivators but also menu taboos—mostly because they’re used extensively in lowbrow chains like Chili’s and Applebee’s. This illustration “is as far as a restaurant of this caliber can go, and it’s used to draw attention to two of the most expensive orders,” Poundstone says.

There are also sensory elements. I nearly fell out of my chair laughing when I saw this tweet:

Why is this interesting?

Comedy aside, it is a thing: our primal senses are on high alert. A sizzling platter hits something in the brain, and makes you more hungry, or at the very least, have order envy. This tweet was a direct hit, judging by the retweets, responses, and smoke it threw off.

A Medium post unpacks the, wait for it, Fajita effect.

Long before the term became popular, Chili’s sizzling fajitas went viral. Cooks called it the “fajita effect”: When the first order of the night came into the kitchen, the cooks fired up several skillets and started prepping ingredients for the bunch of orders that always came soon after. The boom moment of the first sizzle of the night always kicked off a multisensory chain reaction that made the whole dining room want the dish... ...It even put the sizzling sound in its first TV ad. While other restaurants tried to make fajitas that tasted better or looked fancier than the competition’s, Chili’s kept the recipe simple and relied primarily on the sizzle to not only turn heads but also trigger a barrage of senses: you hear them, then you notice the smoke and smell the aroma. Add up all of that, and you don’t just taste or see a neat-looking dish with Chili’s sizzling fajitas. You experience it. No other sensory input is more efficient than sound in helping craft these kinds of experiences. The right sound at the right time has the power to tell a rich story.

It’s not just fajitas: if you’ve ever dined at a Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse, or at a Wolfgang’s in New York, they often send out your steak sizzling in a rich bath of butter. Ever had saganaki at a Greek restaurant, replete with flames? It is a multisensory experience: you hear the sound, you smell the food, you see this dish is presented in its ephemeral perfect prime, ready to eat.

It’s not just about the food, it is about the theatrics of the food. Which often can cause the ever-important upsells or mini virality within the restaurant. It is making me hungry just thinking about it. I’ll have the steak, medium-rare. (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

My daughter, recently in. Greece, ordered saganaki. It came flame-less. She was too intimidated to ask the server, but we are assuming the flames are the American version!