The Skunkworks Edition

On secret company projects, Winston Churchill, and Apple.

John Peabody (JP) is a friend of WITI. He writes the excellent Substack NESS.

John here. I was reading Douglas Brunt’s The Mysterious Case Of Rudolf Diesel, an excellent biography of the diesel engine inventor, when I came across a footnote about Winston Churchill. Turns out, when Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty (the head of the navy) he helped drive diesel engine adoption in England’s fleet, as well as essentially piloting the invention of the tank:

“Churchill also deserves credit for pioneering the battle tank in World War I. When the British army failed to take up design plans for the project, Churchill overstepped the bounds of the navy to form the Landship Committee in February 1915 to develop an armored vehicle for the war. Engineers worked in secret. In typical English fashion, even men providing security for the plant didn’t know what the project was and were told that the materials arriving were for the construction of water tanks. ‘Tank’ became a code name for the operation, then was adopted as the name of the armored vehicle itself.”

Why is this interesting?

Aside from being a notable nugget of military history and another great Churchill story, it also made me wonder if this was the first great “skunkworks.”

What’s a skunkworks?

In my career, a “skunkworks” project is shorthand for one that’s run independently in secret, to circumvent organizational bureaucracy in pursuit of something that wouldn’t otherwise be possible to create or engineer.

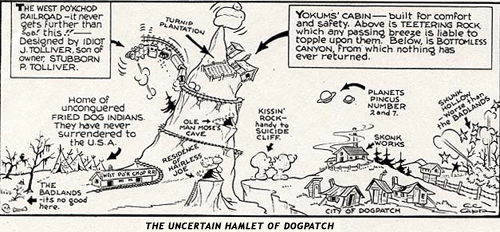

I did some research, and it turns out the term “skunkworks” came from another military project — one in 1943 to produce America’s first jet fighter. The name was lifted from the comic strip Li'l Abner, in which Skonk Works was a "dilapidated factory located on the remote outskirts of Dogpatch."

Skunk Works teams based in Palmdale, California, Fort Worth, Texas and Marietta, Georgia went on to develop numerous airplanes during the following decades, including the SR-71 Blackbird in the 1960s. According to an article on the Michigan Tech site, the "rapid prototyping approach was a cornerstone attribute of Skunk Works that allowed for this innovation, great for shopping many ideas and using failure as building blocks to success."

I’ve been invited into one or two skunkworks projects in my career, though nothing impactful or even notable came from them. They were just projects born of bureaucratic frustration, a gamble to build something great, that if good enough or successful would win praise, and if not, would be quietly forgotten. The air of rebellious skunkworks secrecy and optimism helps get a select few on board and excited to build something unconstrained by usual approval processes.

Along with Churchill’s tanks and the SR-71 Blackbird, another great skunkworks project, and perhaps one of the most commercially known, is the first Mac computer. Steve Jobs led a skunkworks project at Apple to create an affordable consumer-facing computer. The result was a computer with a more graphical interface and a mouse, like the ones we all know and use today.

It’s interesting to me, first, that “skunkworks” is yet another term we use in business that’s lifted from the military. But also, that so much of history’s successes—from Churchill to Apple—required “skunkworks” tactics to get over the line.

Additional Reading:

Lockheed Skunk Works Story – 80 Years of Innovation

DR. DIESEL VANISHES FROM A STEAMSHIP; Inventor of Oil Engine Missing After a Journey from Antwerp to Harwich.

(JP)

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & John (JP)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) with editing help from Louis Cheslaw about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.

Fun article! Thanks