The TV Schedule Edition

On entertainment, technology, and shared experiences

Matt Locke (ML) is a WITI reader and the Director of Storythings, a content studio in the UK. He previously wrote the UK Baseball Edition.

Matt here. If I was to ask you what was the most important invention of the 20th century, you might mention the car, the television, the computer, or the internet. But there’s another invention that had such a huge impact on culture and society that people would organize their lives around it, and it drove the growth of multi-billion dollar industries. Despite this, most of us wouldn’t think of it as an invention at all, as it seems to have always just been there. So here’s a brief history of one of the most important overlooked inventions of modern times: the TV schedule.

Like all innovations, the TV schedule didn’t come out of nowhere—it built on existing concepts, and adapted them to a new need. Organizing a timed schedule of different entertainment goes back centuries, with mixed playbills common in Victorian music halls. But in the early 20th century a new problem emerged, caused by a radical new communications technology. Telephone networks were starting to emerge, and some entrepreneurs saw them not just as person-to-person communications devices, but as broadcast devices that could send the same content into thousands of homes at once.

In the late 19th century services like the Théâtrophone emerged to broadcast live theatre and opera over telephone networks. But the timings of these were still dictated by the physical venues and performances, and the number of simultaneous listeners was limited. Tivadar Puskás, a Hungarian inventor who had worked with Thomas Edison, saw the potential for something completely new. He had invented the multiplex switchboard, which massively upgraded the ability to send the same telephone signal to multiple receivers. Edison’s technology could reach 50 simultaneous receivers at once, but Puskás’s multiplex could reach half a million.

Puskás used his multiplex to launch the first true ‘broadcast’ service—the Telefon Hírmondó, a “telephone newspaper” that broadcast news, stock prices, weather updates and opera performances through one-way telephones installed in subscribers’ homes. This gave Puskås a new problem—how should he organise the content for his subscribers? As he was broadcasting from his own studios, he didn’t have to stick to the opening times of a theatre or opera. And unlike a physical newspaper, he could continue publishing updates all day.

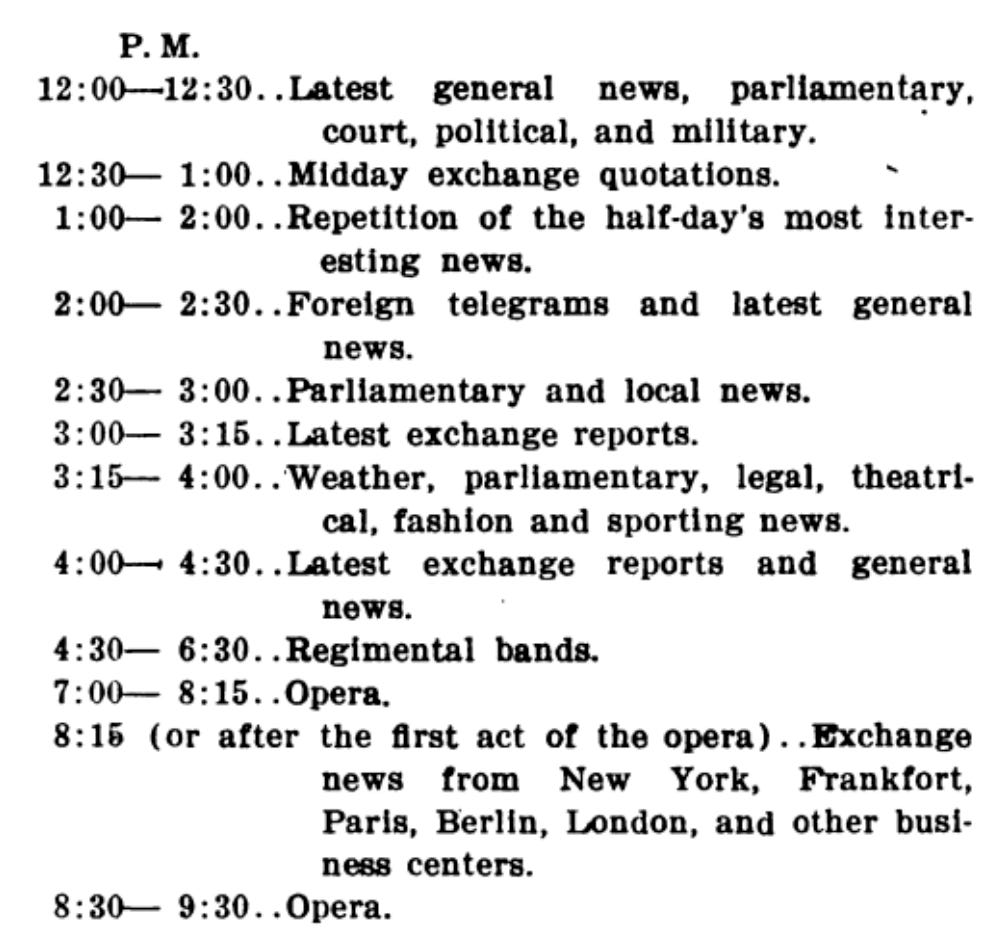

His solution was to organize the content around the times of the day, breaking it up into hour, half hour or quarter hour chunks. A sample schedule from the Telefon Hírmondó in 1907 still looks remarkably similar to TV and radio schedules today, with news updates on the hour, light entertainment in the early evening, and even a repeat at 1pm.

Why is this interesting?

The telephone newspapers were a short-lived innovation, but pioneers like Puskás took what they learned about broadcasting into the new world of radio, bringing with them the schedules they’d used to organis\ze content for their listeners. Radio schedules were then, in turn, copied by the early TV stations in the 1930s and 1940s, and by the second half of the twentieth century, the TV schedule was a dominant and hugely influential force on mainstream culture.

When I worked at the BBC and Channel 4 in the 2000s, my biggest surprise was that the real power-brokers in broadcasting wasn’t the star talent or TV execs, but the schedulers. Their understanding of ratings, audience data and their competitors’ schedules made them masters of a dark art, with the power to make or break a TV show by deciding where to place it in the schedule.

Alongside broadcasting, the TV schedule also had a huge impact on the newspaper and magazine industry. TV Guide, first launched in 1948, reached a peak of 19 million sales by the 1980s, making it one of the highest circulation magazines in the US. In the UK the TV schedule was regulated by government, with only two publications allowed to print the schedules—Radio Times for the BBC channels, and TV Times for ITV and Channel 4. That’s how thing went until 1991, when a long campaign from Time Out founder Tony Elliott finally led to the deregulation of TV listings.

The TV schedule organized the attention of millions of people at the same time, sharing the same experience, whether it was Richard Nixon sweating in a presidential debate, Neil Armstrong stepping foot onto the moon, or finding out who shot JR. These live, synchronous events created a kind of public sphere at a scale that had never been seen before, and we’re unlikely to see again. Sports are the only TV events that get close—on the list of most-watched US TV programs of all time, the only entries from the 2000s are Superbowls.

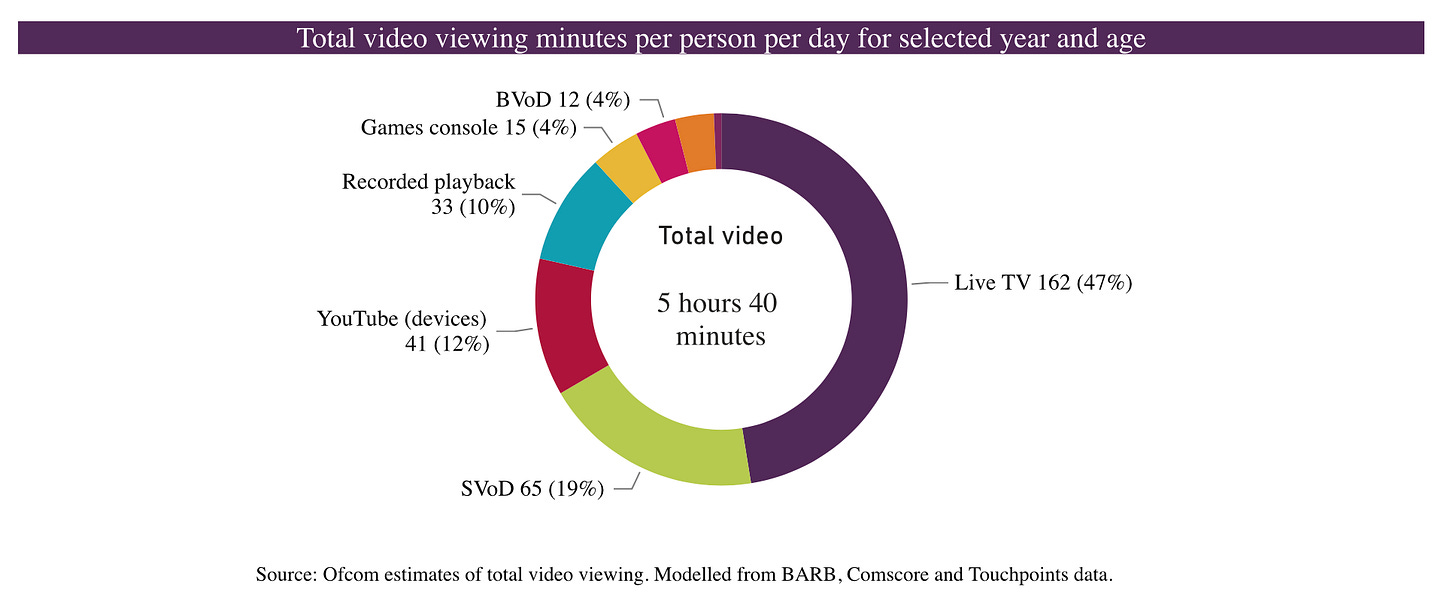

For nearly a century, a simple list, based around the hours of the day, structured the daily habits of millions of people, shaped the careers of politicians and celebrities, and powered a multi-billion dollar advertising industry. As we spend less time watching live TV, and more time on digital platforms, that power is now passing from the TV schedule to another way of organising our attention—algorithmic streams. (ML)

Chart of the Day

Ofcom’s 2021 Media Nations report showed that for the first time, Live TV accounted for less than half of all UK video viewing:

Quick Links:

Nikola Tesla’s first job was working on the Budapest Telephone Exchange for Tivadar Puskás and his brother Ferenc. I love connections like this - they explain how important communities and networks are to innovation. (ML)

Tony Ageh, Head of Digital at NYPL, is one of the few people I know who has worked with TV schedules from print mags like Time Out through to VOD services like the BBC iPlayer. This talk he did for our The Story conference in 2014 is a fantastic explanation of why list formats like TV Schedules are so powerful. (ML)

This history of Netflix’s personalisation tech is a brilliant insight into how media is changing after the schedule. (ML)

The Beatles first appearance on the Ed Sullivan show on Feb 9th 1964 is still one of the most watched TV shows ever. Fred Kaps, a journeyman magician, had the dubious honour of being the act that had to follow The Beatles on that show.

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Matt (ML)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).