Nick Parish (NP) has been a long-standing friend of WITI since his days as a junior reporter on the NY Post’s sports desk. He’s since worked in editorial, strategy, and product design. He lives in Portland, where he teaches fly-fishing and writes about it at currentflowstate.com.

Nick here. Last week in Newport, Oregon, Dungeness crab season was in full swing. Boats moved moving in and out of Yaquina Bay while sea lions bellowed and snapped at each other from nearly every floppable surface.

I was in Newport to speak at a conference held in the Gladys Valley Marine Studies Building at the Hatfield Marine Science Center, the anchor of Oregon State University's coastal campus. Nestled on a 70-something-acre protrusion of land below the stately Yaquina Bay Bridge, the Center is made up of several dozen state and federal buildings, together forming a nerve center for Pacific science. The cluster houses not only OSU labs and classrooms but also outposts of the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Food and Drug Administration, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, and a busy boat ramp and marina.

So, if your honey-do list has you wanting to drop a boat, renew your fishing license, report a polluter, and talk with someone about data from Station 46281—a buoy out by Stonewall Bank—the Hatfield Marine Science Center is a one-stop shop.

Why is this interesting?

For the two days I was in and around the Hatfield Center, my death-by-tsunami likelihood was probably as low as it'll ever get on the Oregon Coast.

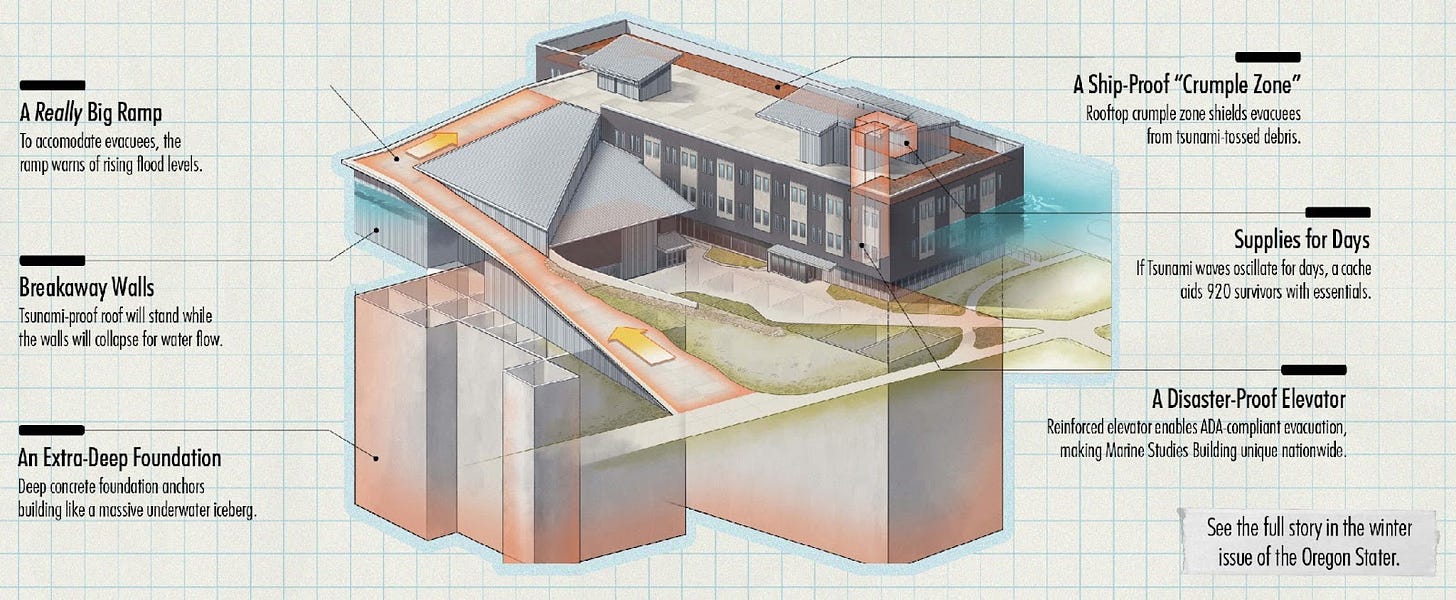

That's because the Gladys Valley Marine Studies Building, the jewel in the Hatfield Center treasure chest, is designed to withstand a 9+ magnitude earthquake and "XXL" tsunami event. The GVMSB, as it is known, is a vertical evacuation structure, a unique architectural feature making it a modern-day Noah's ark.

If you're like me, you associate evacuation with out and down, not in and up. But the GVMSB is designed to elevate people above a tsunami inundation, and protect them from debris: massive ships moored nearby, or parts of the aforementioned infrastructure like buildings and bridge pieces.

Designed by Yost Grube Hall Architecture, and completed in 2020, the building has multiple paths to the top, including an exterior ramp and multiple stair and elevator routes accessible 24/7/365. The elevator has a backup generator and can move up to 200 mobility-challenged people in the twenty-minute window between a quake alarm and the arrival of a tsunami wave.

Once on the roof, a cache supplies "water, food, sanitation, shelters, communication, personal warmth, lighting, and trauma first aid supplies" for up to two days. (If only the Go Bag Boys could get ahold of that spreadsheet.)

I'm not tsunami-anxious, but it was certainly calming to understand the building’s features. Ever since Kathryn Schulz' Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Really Big One” appeared in the New Yorker in 2015—and scared the pants off the majority of Cascadians—coastal communities have taken earthquake and tsunami preparedness seriously.

Visit the coast and inundation zones, evacuation routes, and estimated high-water marks are well signed and clear. Hotels and short-term rentals help visitors understand what to do when a siren goes off.

But there's still an ongoing sense of unpreparedness when it comes to protecting places where people frequently gather—schools, for instance—that may be vulnerable when the Cascadia Subduction Zone finally rubs itself the wrong way.

Iconography is clear at the GVMSB: a sign in tsunami blue (thank you Wellington, NZ) juts from the building corner, with a simple suggestion: walk briskly, roll quickly, if that wave is coming.

Inside the building, amidst the laboratories and manufacturing spaces and visitor centers, and the artworks that keep you company—Emily Jung Miller's woven ghost net objects and Dwight Hwang's gyotaku opahs—there's a striking sense of serenity oddly close to the pounding surf. (NP)

Every post from NP is a gift