Felix Salmon (FMS) joins us for a third WITI today. He previously wrote about the Sackler family and philanthropy for WITI 5/17, and about expensive popular art for WITI 10/9. You can find him regularly over at Axios. And sign up for his Thursday business and finance email Axios Edge. - Noah (NRB)

Felix here. Recently Colin dropped this story into the WITI Slack, about Arnd Erbel, a Bavarian baker who’s making Brezn without yeast. Brezn are the Bavarian form of what Americans call pretzels, but in the rest of Germany this emperor of bakes is just called a Brezel—or, for reasons that we’ll come to in a minute, a Laugenbrezel. The story reminded me of my favorite YouTube video of all time, an 11-minute mini-documentary called La Laugenbrezel that has been watched 25,426 times. I don’t like to think about how many of them are just me re-watching it.

Why is this interesting?

Noah likes to troll me with his love for hard, tasteless American pretzels. Other Americans claim to like the doughy version that can be bought from street vendors selling dirty-water hot dogs, or even the bizarre “artisanal” pretzels that briefly cropped up next door to me at a place called Sigmund’s when I lived on Avenue B and 3rd Street.

The NYT wrote up Sigmund’s after it opened, with a photograph of a pecan-and-caramel pretzel which to this day is I think the most obscene thing that august newspaper has ever published. Amazingly, the headline on the piece is “Making Soft Pretzels the Old-Fashioned Way”—something that could only be written by someone who has never been to southern Germany.

I’m half German. More to the point, I’m half Swabian. My mother grew up in Bad Cannstatt, a town just east of Stuttgart whose main claim to fame is the Brezel. (Also, Mercedes-Benz, but the Brezel always comes first.) When she came to visit me in Berlin one summer, she spent two full days trying to find a decent Brezel, and then just gave up, dejected. It’s basically impossible to find a good Brezel outside the three states of Swabia, Bavaria, and Baden, each of which has their own distinct version of the bake. (That said, I’ve found some decent attempts in northern Switzerland, and honestly, a lot of the Baden versions are not that great.)

A true Brezel has the same kind of external bite as a great bagel, although it’s much softer on the inside. If it’s Swabian (as it should be) then the arms are nice and crunchy, in perfect contrast to the doughiness of the belly. It’s also baked with large salt crystals that provide a perfect surprising tang when they hit your tongue. And just like the bagel, the Brezel is a defiantly local speciality. You can’t get a good bagel (or pizza) in San Francisco; you can’t get a good Brezel in Berlin or New York. Sorry folks, that’s just the way it is.

I’m going to reserve judgment when it comes to Erbel, Colin’s Bavarian baker, because I haven’t had his Brezn. But he works without yeast, which is weird; he doesn’t use lard, which is bad; and well, he’s Bavarian, which makes him automatically suspect to a Swabian partisan like myself. I also disapprove of Erbel’s idea of adding fine salt after baking: it loses the crucial texture of the salt. Also, just going from the photographs, he’s burning them. A Brezel should be light brown, not dark and blistered, although I did once have a very good and quite dark Pfefferbrezel, or pepper pretzel, in Bayreuth.

Photos from the Saveur Brezn article.

There’s a very good reason you can’t get a good Brezel outside southern Germany, and that reason is volume. Frank, the store in the YouTube video, is on a quiet street corner in Bad Cannstatt, and it makes 2,500 of them per day. Substantially all of them are sold to the store’s neighbors, who would never dream of starting their day without a Brezel for breakfast. Up the street is Treffinger, which serves exactly the same purpose for its own micro-neighborhood. You get up in the morning, you go down to the bakery, you buy your Brezeln, you rush them back home while they’re still warm from the oven, and then you eat them with your family. You do this every day, and every day the master baker wakes up at 4am to bake them for you, subtly adjusting his baking technique to that day’s warmth and humidity.

The economics of the Brezel only work if you can turn out a couple of thousand of them per day. That helps to pay for the big steam ovens and all the other machinery you can see in the video, including the device that sprays the dough with lye, or caustic soda, just before they go into the oven. (Hence the name Laugenbrezel, or lye pretzel.) A Brezel is like a razor blade, or an espresso: The more you make, the higher quality each one becomes.

A Brezel is similar in some way to the classic NYC slice. It needs high-end professional machinery to make, and it’s best eaten within minutes of coming out of the oven. (The Brezel wishes it had the shelf-life of a French baguette.) As a result, the stores selling it need a steady stream of local customers.

So next time you hear someone like Noah waxing lyrical about the wonder of “pretzels” that taste exactly the same as they did three weeks ago, just ask whether he’s ever been to Stuttgart. If the answer is no, then he almost certainly doesn’t have a clue what he’s talking about. (FMS)

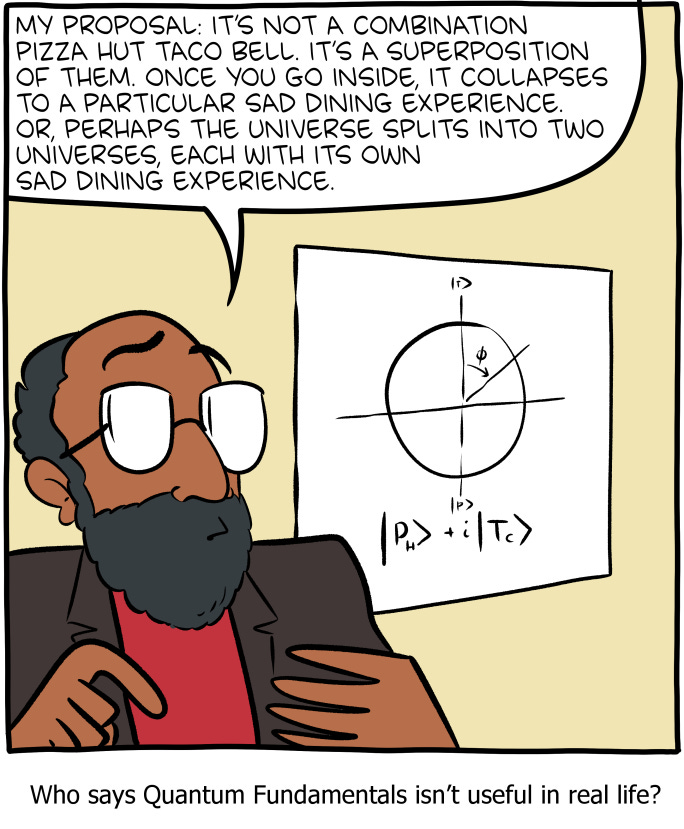

Comic of the Day:

Courtesy of Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal. (NRB)

Quick Links:

Speaking of the NYC slice, here’s my favorite theory on why it’s so much better than what you can find in other cities: We’ve got older ovens. "As you cook, some ingredients vaporize, and these volatilized particles can attach themselves to the walls of the baking cavity … The next time you use the oven, these bits get caught up in the convection currents and deposited on the food, which adds flavor." (NRB)

Matt Levine on being able to buy fractional shares of stock (NRB)

What makes a good maze? (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Felix (FMS)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).