Why is this interesting? - The Curiosity Curve Edition

On code, cooking, and finding better ways to teach people valuable skills

Yesterday we did a giveaway for Joanne McNeil’s new book Lurking. We’re excited to announce the winner is Liz. We’ll be in touch to get your book shipped out. Thanks to everyone that entered and hope you’ll still check it out. - Noah (NRB)

Noah here. Twelve years ago I taught myself to write code. I had grown up making websites for people and had hacked around my share of PHP templates, but I didn’t know how to build something from scratch. Prior to that, I had tried to read books and take online coding courses, but nothing stuck. Then, I had an idea one night to build a thing that could collect people’s perception of brands, and it was the motivation I needed to fight past the starting slog and be able to hack something together on my own.

That experience taught me a lot about what I need to learn something new. (I also recognize not everyone learns the same way.) In addition, it planted a theory in my head about the problem with how coding and a number of other things are taught: we try to get people to learn as if they’re going to become professionals in the field, not amateur hackers using the skill to complement whatever else they do. In code, this is starting with a bunch of core concepts about computer science instead of digging in on making things. In foreign language learning, this is trying to teach 12-year-olds how to conjugate verbs in French instead of how to say some common phrases. (Colin covered this a few months ago in the Language Learning Edition.)

I think this even extends to teaching kids writing, where a focus on spelling and grammar can kill the spirit of storytelling. It’s not that skills things don’t have a place, but teaching someone to be conversational (or the discipline equivalent) is a very different process than teaching them to be a professional in the field.

Why is this interesting?

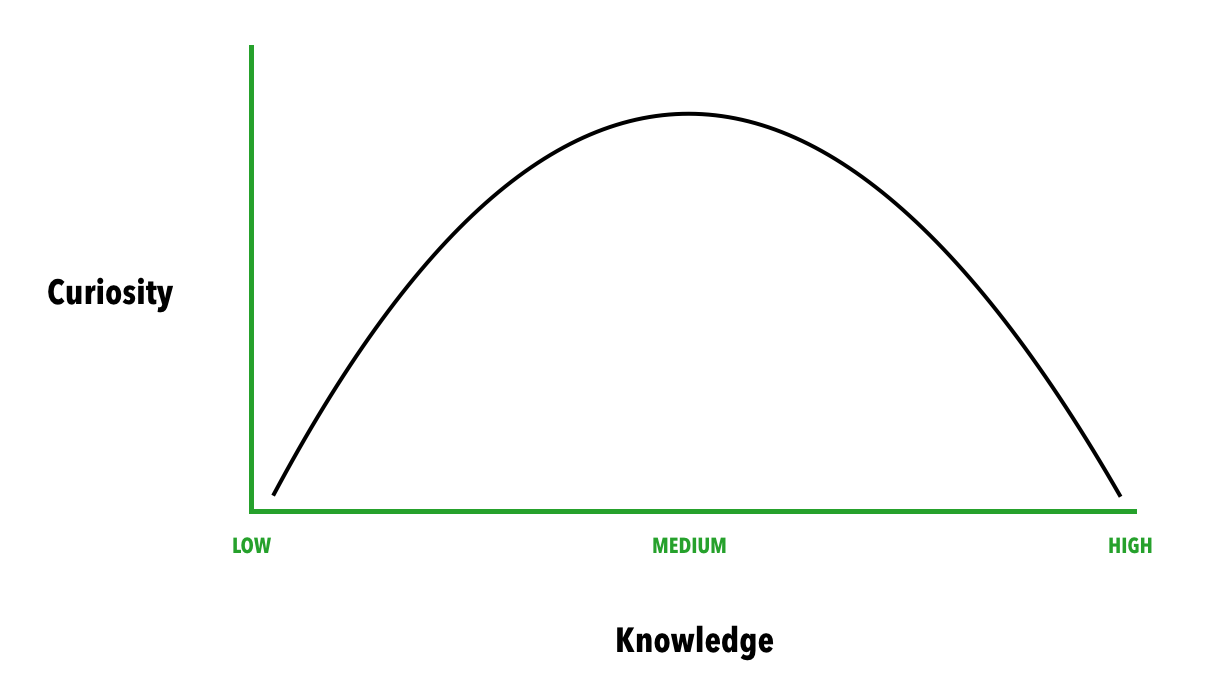

In Ian Leslie’s book Curious, he offers up a very sensible graph to describe the relationship between knowledge and curiosity. The gist, as shown below, is that curiosity is at its lowest when knowledge is either very low or very high: the former leaves you nothing to get you started with and the latter without anything left to look forward to. This seems particularly relevant for this professional learning conundrum, as those of us with a desire to learn a new language (whether it’s spoken or code) are left without the necessary knowledge to spark the compounding effects of curiosity.

This was all perfectly stated (as usual) in a recent post by Robin Sloan comparing coding to cooking. Here’s the kicker:

I am the programming equivalent of a home cook.

The exhortation “learn to code!” has its foundations in market value. “Learn to code” is suggested as a way up, a way out. “Learn to code” offers economic leverage, a squirt of power. “Learn to code” goes on your resume.

But let’s substitute a different phrase: “learn to cook.” People don’t only learn to cook so they can become chefs. Some do! But far more people learn to cook so they can eat better, or more affordably, or in a specific way. Or because they want to carry on a tradition. Sometimes they learn just because they’re bored! Or even because—get this—they love spending time with the person who’s teaching them.

The list of reasons to “learn to cook” overflows, and only a handful have anything to do with the marketplace. This feels natural; anyone who has ever, like… eaten a meal… of any kind… recognizes that cooking is marbled deeply into domesticity and comfort, nerdiness and curiosity, health and love.

That sums it up well. Cookbooks almost exclusively don’t try to teach you to cook as if you will work in a kitchen, they know you’re just trying to make something delicious for you and your family. The approach they take as a result pushes you to learn some basics and then get your hands dirty as soon as possible, ideally raising your knowledge and pushing you up on the curiosity curve. Taken this way, learning conversational code doesn’t even need to extend to the point of building your own app: being able to write a bit of javascript to pull down some data from an API, SQL for a little analysis, or even just some regex—a kind of pattern-matching language—for better find and replace, can be a nice productivity boost. While you’ll always need a good base of knowledge to get going with any new skill (a fact Leslie outlines well in his book), I wish more fields felt comfortable recognizing the kind of knowledge to focus on at the start. (NRB)

Recommendation of the Day:

I really like the store Best Made Co. Everything I’ve bought from them has been unique, and there’s an emphasis on quality with a smart aesthetic and Mallmann-esque worldview of nature and the outdoors. Check out their chambray shirts, their down jackets (850 fill, super warm), and some of their merino products. There’s also a section of Japan-made items from a Kanagawa travel guide to hand-dyed Tenugui. (CJN)

Quick Links:

A peek at architects private homes (CJN)

LL Bean: Why was the brand forgotten (CJN)

Silicon Valley and work culture (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).