Why is this interesting? - The Double Jeopardy Edition

On popularity, loyalty, and the unexpected relationship between the two

Noah here. In last week’s Loyalty vs Availability Edition, I wrote about how the idea of loyalty in marketing—how often you buy from the same merchant—is driven largely by availability. The key point is that however much you want a Coke in a Taco Bell or a Frappucino in the middle of Boston, you’re probably getting a Pepsi and whatever Dunkin’ Donuts calls a Frappuccino (a frozen coffee?). Even the most loyal customers of a brand can’t be loyal if the product isn’t available to them.

Some folks pointed out the connection to the “double jeopardy” law in marketing, which is actually a statistical observation that the largest market share brands are also consistently the most frequently purchased. Since I’ve spent some time digging into the history of this bit of empiricism, I thought it might be worth exploring here.

Why is this interesting?

At the center of most business, and certainly marketing, is the question of how to drive growth. The answer, while presented in many different ways, almost always comes down to two options: Find more customers or get your current customers to buy more often (or, at the very least, not buy less often).

If you view these as separate questions, you get something like BCG’s growth-share matrix, which suggests different approaches depending on whether you’re focusing on a new or existing market with new or existing products. The only issue is that there is quite a lot of empirical evidence suggesting these aren’t actually two different problems.

That evidence starts with a 1963 book called Formal Theories of Mass Behavior by Columbia University sociologist William McPhee. In it, McPhee writes about an interesting polling phenomenon related to movie and television stars: The fewer people who know about a star, the more they dislike them compared to a more well-known counterpart. If that seems strange to you—why should there be any correlation between how popular a star is and how those people feel about them?—McPhee agreed. “This seems absurd,” he wrote. “The number of other people who have not yet become familiar with an alternative should have nothing to do with whether or not those who have become familiar with it like it.”

Why is it that stars known by fewer people are liked less than stars known by many people? The most obvious answer would be that the less famous ones just aren’t as good. Except, as McPhee described, that doesn’t seem to be the case. “The explanation is that the lesser-known alternative is known to people who know too many competitive alternatives.” In other words, those who know more, have access to more obscure choices, but they also seem to like those niche choices less.

If that sounds like it flies in the face of ideas about the world going more niche and the long tail, Harvard Business School professor Anita Elberse would agree. When she looked through data from video services in 2008 she found that McPhee’s 45-year-old ideas held up:

My research also answers the question, How much enjoyment is derived from obscure versus blockbuster products? We can all easily imagine the extreme delight that comes from discovering a rare gem, perfectly tailored to our interests and ours to bestow on likeminded friends. This is perhaps the most romanticized aspect of long-tail thinking. Many of us have experienced just such moments; they are what give Chris Anderson’s claims such resonance. The problem is that for every industrial designer who blissfully stumbles across the films of Charles and Ray Eames, untold numbers of families are subjecting themselves to the likes of Sherlock: Undercover Dog. Ratings posted by Quickflix customers show that obscure titles, on average, are appreciated less than popular titles.

Elberse sums up the “double” part of “double jeopardy” like this: “First … a disproportionately large share of the audience for popular products consists of relatively light consumers, whereas a disproportionately large share of the audience for obscure products consists of relatively heavy consumers; and second, that consumers of obscure products generally appreciate them less than they do popular products.” Basically most people who buy the big brands don’t buy them all that often, and when heavy buyers are forced to buy a niche alternative they don’t like it all that much.

That’s why availability matters so much. The biggest brands, whether they be Coca-Cola or Starbucks, get a double boost from both being the most well-known and, therefore, also more likely to be liked more. While there are some interesting questions about how this will develop as brands continue to go direct-to-consumer, to my knowledge it has shown no real signs of letting up. As I see it, DTC brands are mostly niche players (<5% market share) with an interesting loyalty mechanism. At the end of the day, though, they’re still subject to the same availability problems as everyone else. (NRB)

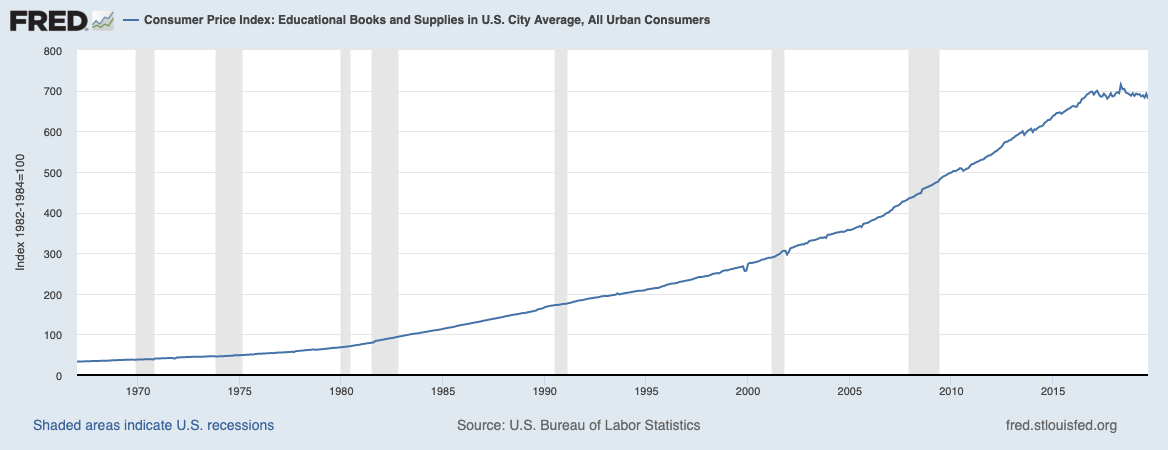

Chart of the Day:

The price of textbooks finally seems to have peaked. (NRB)

Quick Links:

A month ago I tweeted at Quote Investigator after I ran into a quote that was supposedly from science fiction writer Frederick Pohl about how it’s easy to predict the car but hard to predict traffic. I then went down a research rabbit hole trying to find the original source. Well, he just wrote up the whole thing and I got a bit of recognition at the end for my research, which is probably amongst my nerdiest achievement. (NRB)

I’ve always been a sucker for redesign explainer. Here’s the journal Nature on their design decisions. (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).