Colin here. One of my favorite albums of all time is DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing. It is a moody masterpiece from 1996, comprised of long-forgotten breaks and samples. The debut did very well initially in the UK and slowly permeated the US market, now standing as a classic of its time. What I love about it is the simplicity of production combined with painstaking sourcing, editing, and composing. When asked about his approach to making the whole album on essentially just turntables and an Akai MPC-60 MKII sequencer-sampler, here’s what Shadow said in a 1997 interview:

It was all about chopping to me. I never had the luxury of taking extended samples. There are lots of overdubs on the album, as well. But all the record was 100% sample – or vinyl-based. All the sampling was done on the MPC. It all went straight from turntable to the MPC to tape. And any other things you hear were done straight off the turntable, pitched in. Like, if a song is in a certain key, and I overdub a string bit, I have to manipulate the pitch control on the turntable until it works.

What truly stands out is how expressive and nuanced the drums are. They aren’t played live on a drum set, but rather tapped out on the “pads” or hyper-responsive controls of the MPC, an instrument that allows the loading, triggering, and composition of beats, bass lines, and other elements. The machine is a cult piece of gear among producers and beat makers. It allows a level of expressiveness and touch that brings depth to the music. Music technology has since become much more sophisticated, but people still regularly use them because of the magic contained.

Why is this interesting?

I’ve long been fascinated by how the best beatmakers and producers do what they do, and break convention to sound unique. People like Timbaland, Clams Casino, Dabrye, and Photek all have beats that you’d almost immediately recognize as theirs. So, I went down the wormhole a little bit and watched this incredibly interesting explainer video on how J. Dilla, a cult producer who passed away too early, made one of his iconic albums, Donuts. He knew his MPC, in this case, an MPC3000, so well, that he knew how to subvert the presets and humanize them.

One such example is when you are programming a track, there’s a setting that subtly autocorrects you if you are slightly off time. He turned this off and kept in the small smudges and misfires. Questlove, the drummer for the roots said some of the beats sound like a “drunk three-year-old” (which he was saying as a compliment) and called it a “liberating moment” in his thinking about making music. The point here is that Dilla knew the machine so well that he could actually bend and twist the settings and the robotics to make something that felt wobbly, warm, and imperfect. It is probably no accident that this album is such a crowd favorite over the years. There are texture, soul, and mistakes in ample portions and it reveals more on every listen. And this focus on just the beats isn’t even getting into the editing and manipulation of vocal and other instrumental samples, which is worth a watch of the entire video to unpack. How he morphs and recontextualizes a weird old anthemic Georgio Moroder Italo synth snippet is the essence of musical creativity. (CJN)

Design of the Day:

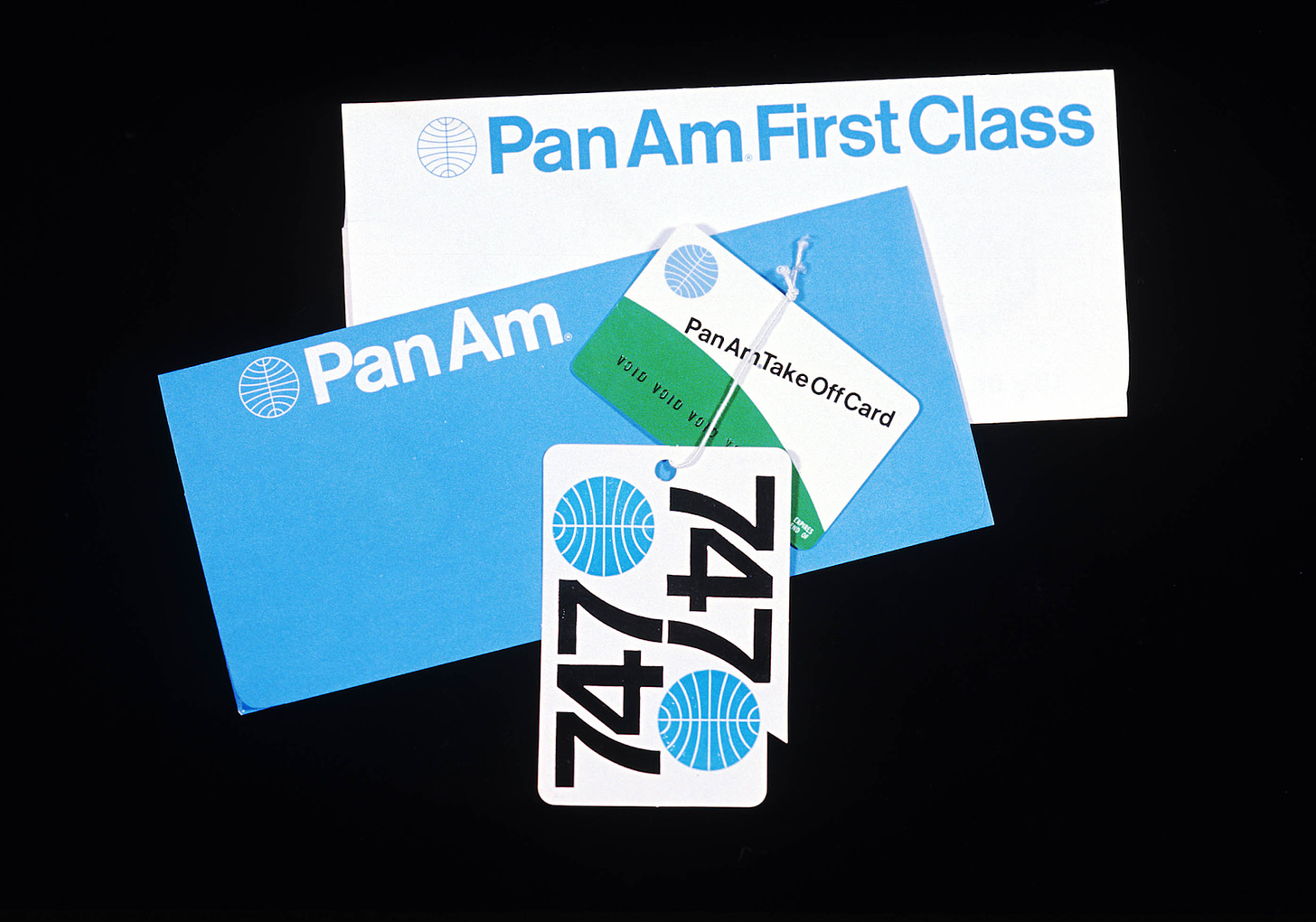

Vintage PanAm gear. First spotted via Michael Bierut on Twitter. The identity was done by design firm Chermayeff & Geismar in the early 1970s. Be sure to check out the posters as well. (NRB)

Quick Links:

BBC banned in China (CJN)

Go sign up for Ben Dietz’s excellent SIC newsletter. (CJN)

Microsoft made an approach to buy Pinterest (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)