Why is this interesting? - The Feral Cities Edition

On megacities, urbanism, and tribal politics

Noah here. Back in 2013, Tim Harford, one of my favorite thinkers and writers, hosted a short-lived podcast called Pop-Up Ideas. The description says the series was made up of “talks inspired by ideas in anthropology, culture and the social sciences,” which gave Harford enough latitude to invite smart people to talk about anything they wanted. One of the episodes that stuck with me was counter-insurgency guru David Kilcullen talking about the idea of feral cities. The concept was first raised by professor and retired Navy commander Richard Norton in a 2003 Naval War College review paper. In the paper, Norton describes a feral city as “a metropolis with a population of more than a million people in a state the government of which has lost the ability to maintain the rule of law within the city’s boundaries yet remains functioning.”

He goes on to explain:

In a feral city social services are all but nonexistent, and the vast majority of the city’s occupants have no access to even the most basic health or security assistance. There is no social safety net. Human security is for the most part a matter of individual initiative. Yet a feral city does not descend into complete, random chaos. Some elements, be they criminals, armed resistance groups, clans, tribes, or neighborhood associations, exert various degrees of control over portions of the city. Intercity, city-state, and even international commercial transactions occur, but corruption, avarice, and violence are their hallmarks.

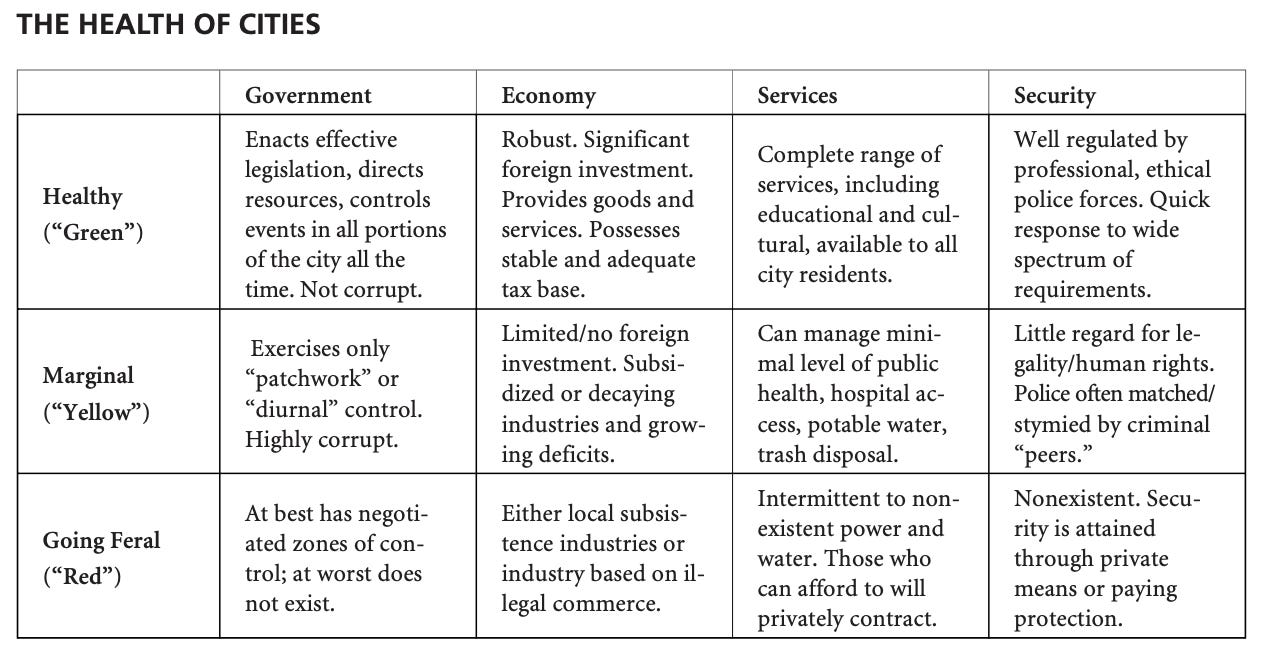

Further down, Norton goes on to offer a taxonomy to describe the health of cities: green for healthy cities, yellow for marginal ones, and red for those “going feral.”

Why is this interesting?

Mogadishu is the canonical example of a feral city, as told in the book and movie Black Hawk Down. But, as Kilcullen explains on the Pop-Up Ideas episode, how it happened isn’t well understood:

Now, people often assume that what happened to Mogadishu was that the state collapsed. The Civil War broke out, and then the city went feral. But as the Somali writer Norden Farrar pointed out a few years ago, actually it was the other way around. In the generation after Somali independence in 1960, an enormous number of rural people migrated from the Somali countryside into the capital city and the city's population swelled dramatically. The town just couldn't handle the flow of people, its infrastructure and system lack the carrying capacity to cope. Over the next 30 years, warlords and power brokers forged a series of competing fiefdoms that eventually tore the city apart, and ultimately brought down the state. Mogadishu didn't go feral because the state collapsed, rather the state collapse because the city was already feral.

All of this came back to mind last week when I ran across a conversation between Richard Norton and John Spencer, who heads up Urban Warfare Studies at West Point on the Urban Warfare Project podcast. What mainly stuck out to me in the episode was the conversation around how few people are studying the specifics of megacities. Spencer poses a fascinating question to Norton:

Most of our diplomatic relations and understanding of other environments are usually started at the nation level. And most of your foreign area officers are aligned to countries, maybe regions, but never cities. And that's some of our research on megacities. We sent a team in Dhaka and the country team didn't understand really how Dhaka worked, because they're prioritized on the country. … But how are we doing on developing expertise in major urban areas, even if it's feral cities?

Norton’s answer about the potential need to rethink the normal three levels of analysis—system, state, and individual—in the face of the megacity is worth reading in its entirety:

I guess my quick answer is I don't know. But I'm not encouraged by what I run into. I think it's not just your experiences with the embassies. In some ways, it's a reflection of international relations. You think about the three great levels of analysis: there's systemic—so we look at the world as an interrelated parts and there's different theories about how the world works. And then level two, as you pointed out, is state-centric. So it's the nature of the government, it's how bureaucracies work within the state. And then … level one is the individual so we look at leaders and important person who just to figure out how things go. There may be a different level or a sub-level between state and individual, and that could be the megacity. I think we collectively have not looked at that level very much. Now, first off apologies to those who are urban scientists and who are urbanists and futurists who are specializing in cities. But I think the larger discipline is still coming to grips with what it is to have a megacity, what is the impact of a megacity? Obviously, the army has specialized interest in it, but everything from sanitation, to health, to education, the idea of urban hypertrophy, and its explosive demographic growth. These are all things we're witnessing, and the number of experts, and thankfully there are some, I think are comparatively few.

There has been a clear trend towards urbanization happening over the last 60 years (see today’s chart of the day for evidence) and, as Norton, Spencer, and Kilcullen point out, keeping those cities from going feral will likely be one of the great challenges of the 21st century. (NRB)

Chart of the Day:

How Urban is the World? From Our World in Data. (NRB)

Quick Links:

Nice interview with Florence Welch from Florence and the Machine (CJN)

The Arab roots of Sicilian cuisine (CJN)

Everyone’s talking about Fiona Apple. Here’s the New Yorker profile (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).