Why is this interesting? - The Foreign Policy Edition

On hedgehogs, foxes, and how the two approaches work in the arena of foreign policy

Noah here. The story of the hedgehog and the fox has gotten lots of play over the last few years. “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” The distinction, originally from the Greek poet Archilochus, is generally linked back to an essay of the same name by Isiah Berlin. Philip Tetlock, the expert on experts and forecasting, picked up the idea from Berlin, and Nate Silver got it from Tetlock, whose research has found that people who forecast like foxes (using many inputs) do far better than those who take the hedgehog approach (attempting to apply a single worldview).

The problem, as Tetlock outlines in his 2015 book Superforecasting, is that everywhere we look we find hedgehogs. That’s because they make for better sound bites, despite the lack of accuracy:

[Tetlock’s expert political judgment research (EPJ)] revealed an inverse correlation between fame and accuracy: the more famous an expert was, the less accurate he was. That’s not because editors, producers, and the public go looking for bad forecasters. They go looking for hedgehogs, who just happen to be bad forecasters. Animated by a Big Idea, hedgehogs tell tight, simple, clear stories that grab and hold audiences. As anyone who has done media training knows, the first rule is “keep it simple, stupid.” Better still, hedgehogs are confident. With their one-perspective analysis, hedgehogs can pile up reasons why they are right—“ furthermore,” “moreover”—without considering other perspectives and the pesky doubts and caveats they raise. And so, as EPJ showed, hedgehogs are likelier to say something definitely will or won’t happen. For many audiences, that’s satisfying. People tend to find uncertainty disturbing and “maybe” underscores uncertainty with a bright red crayon. The simplicity and confidence of the hedgehog impairs foresight, but it calms nerves—which is good for the careers of hedgehogs.

Why is this interesting?

This came to mind Sunday morning as I was reading an excellent Dexter Filkins piece on Samantha Power, the former US Ambassador to the United Nations under Obama. The shape of the story, essentially, is that Power entered the White House as a hedgehog who saw everything through an interventionist lens. “Power advocated greater interference in countries’ internal affairs in defense of an unwavering principle of humanitarianism,” Filkins explains. In her time there she faced the messy reality of foreign policy, where even the line between unquestionable good and disaster can be blurry. In her new book, which I believe Filkins is ostensibly reviewing, she very lightly comes to grips with some of this. “Much of the book reads as though it were written by someone campaigning for her next job,” Filkins writes, “one that requires Senate confirmation.”

With that said, the article itself is a masterclass in the kinds of tradeoffs that make for reality in the high stakes foreign policy arena. Take this explanation of the choices that surrounded intervention in Libya:

She also refrains from addressing several questions that linger over the intervention, the kind that preoccupied her in her first book. The most basic among them is whether, given the way the intervention turned out, war was necessary. As the uprising gathered momentum, Qaddafi sent a menacing message to Benghazi. “We are coming tonight,” he said, and for rebels who do not lay down their arms “there will be no mercy.” Qaddafi had a well-established record of murder and torture when it came to domestic opponents. But, in the decades during which he had presided over Libya, he had typically suppressed uprisings by killing their leaders, rather than by mounting wholesale massacres. No large-scale massacres had occurred in the cities that his forces had recently recaptured. Was it going to be more than bluster this time? It’s difficult to say. If Qaddafi had put down the uprising in Benghazi, the rebellion might have ended altogether. A tyrant would have remained in power, and many people would have died—but perhaps fewer than died in the intervention.

And it wasn’t just Libya. The “Thin Red Line” policy from the Obama administration about Syria’s use of chemical weapons seemed quite Hedgehog-ian: “The noncombatants targeted by Assad were almost all Sunni, members of the country’s majority population, and so his actions plausibly fit the legal definition of genocide, which Power described in her first book as an irrefutable call to action. But, in office, she found that practical and political considerations overwhelmed the moral concerns.”

In the end, despite what a bunch of experts on a cable news show might want you to believe, foreign policy is a space with a vast grey area where the choices are often between a bunch of bad options. Unfortunately, that kind of answer doesn’t make for appealing media. This is true of television in particular, but even in print it’s hard to find folks who are comfortable with conclusions that don’t land them squarely on one side or the other. That’s a big part of the reason I found the piece by Filkins so refreshing. And while I imagine any foreign policy team has a mix of voices advocating for various approaches, it’s hard to apply the hedgehog approach to a very foxy world. (NRB)

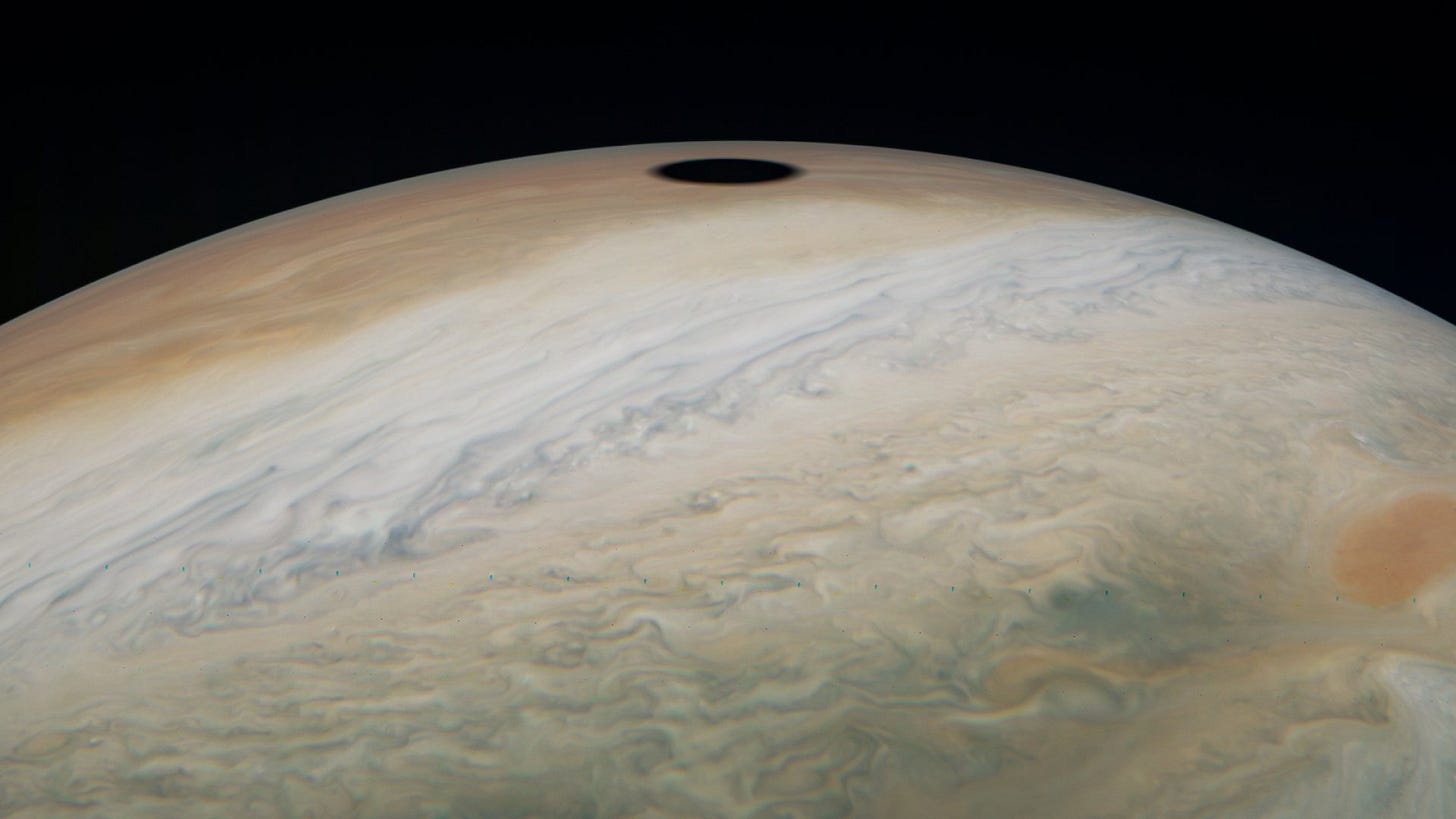

Photo of the Day:

From Twitter user Seán Doran: “The shadow of Jupiter's moon Io is captured by @NASAJuno on the recent 22nd perijove.” (NRB)

Quick Links:

Where will Warren Buffet find his next deal? An FT deep-dive. (CJN)

Three people sent me this ESPN story about the physical toll chess takes on the human body as possible WITI fodder. I have to consider writing a whole edition to try to pick apart the elements of this piece that made them all send it my way. (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).