Why is this interesting? - The Forward This Email Edition

On misinformation, research, and staying informed

Noah here. One of my jobs amongst the craziness of COVID-19 has been the official family pit-stop for all questionable emails prior to forwarding. As a rule, my answer is “no, don’t forward this” on the assumption that good information is probably not coming through a random email but rather from health authorities and other credible sources. While I’m far from an expert in epidemiology, I do consider myself a reasonably competent amateur researcher and a good critical reader, and I trust my instincts when it comes to sniffing out misinformation.

But it’s hard. There’s a lot of bad information floating around out there. This is obviously not a new phenomenon, either for this outbreak or even the internet more broadly. Being able to consume information critically and synthesize it well is essentially the job description of much-maligned journalists. Friend of WITI Felix Salmon wrote about this in 2013 after social media joined the hunt for the Boston bomber:

There’s an art to working out where to find fast and reliable information, and to judging new information in light of old information, and to judging old information in light of new information. And there’s an art to synthesizing everything you know, from hundreds of different sources, into a single coherent narrative. It’s not easy, it’s not a skill that most people have, and it’s precisely where news organizations add value.

Why is this interesting?

I thought it might be useful to outline some of my techniques for keeping myself informed and able to sniff out misinformation. Some of it is specific to Coronavirus, but these are approaches I’ve honed over many years of spending way too much time reading stuff on the internet.

The fine folks at First Draft recently wrote up the 5 quick ways we can all double-check coronavirus information online. While they go into quite a bit more depth than I expect will be feasible for most, their first point is also where I start: “Some stories are too good to be true.” If something in an email that was forwarded to you seems too specific or useful to not have been shared more widely, then it probably isn’t true.

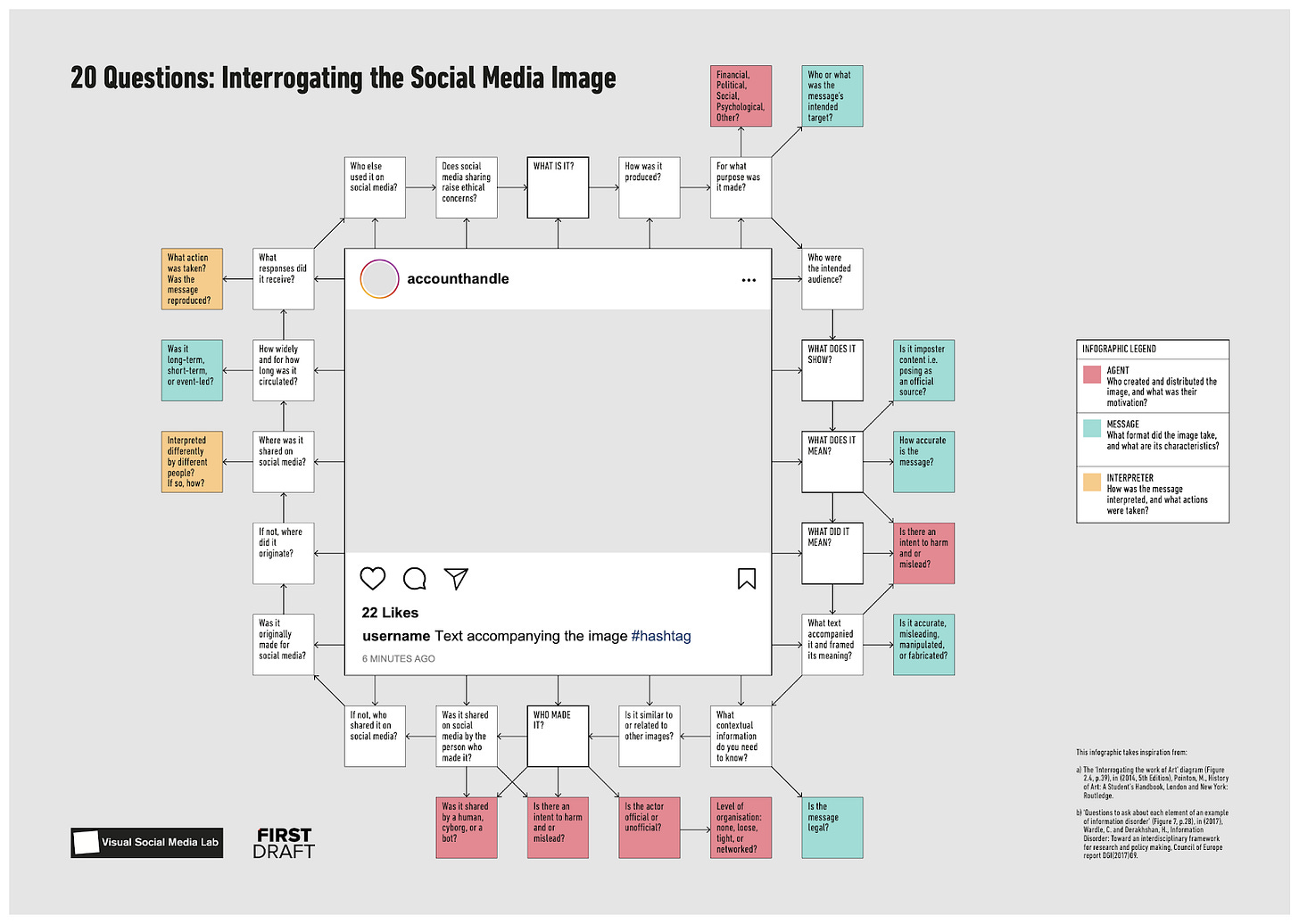

As a rule, Snopes and Google (both regular search and reverse image) are your friends. Checking to see if a) other people are saying the same thing or b) someone has debunked the email/social post/etc. is a relatively easy step to take. (If you really want to go deep, you can consult this great set of questions put together by First Draft and Farida Vis/Visual Social Media Lab specifically for examining social media imagery.)

As far as my workflow, after the sniff test, I move to sources. Are there good ones there? People or institutions I trust or can verify? The closer you are to the source of information, the better it should be. I’ve been working on a Twitter list of COVID-19 researchers, doctors, and journalists. As Laura Helmuth, the science editor for the Washington Post outlined recently:

Look to infectious-disease and public-health experts for solid information, and be on alert for people trying to sell themselves as experts when they aren’t. Lots of misinformation is circulating about coronavirus, and this problem will get worse as the outbreak does. Some politicians are minimizing the danger, some quacks are trying to sell sham treatments or protections, and some anti-vaxxers are weaving coronavirus into their conspiracy theories about vaccines.

And, of course, there are the large publications like the Washington Post, New York Times, and Wall Street Journal. The size matters because the more resources available, the better a publication is able to have accomplished editors looking over everything. Some publications with long lead times, like the New Yorker, also have fact-checkers, adding an additional layer of security. Here’s how New Yorker fact-checker Peter Canby described the process in 2012:

To start checking a nonfiction piece, you begin by consulting the writer about how the piece was put together and using the writer’s sources as well as our own departmental sources. We then essentially take the piece apart and put it back together again. You make sure that the names and dates are right, but then if it is a John McPhee piece, you make sure that the USGS report that he read, he read correctly; or if it is a John le Carré piece, when he says his con man father ran for Parliament in 1950, you make sure that it wasn’t 1949 or 1951.

That last bit—“make sure that the USGS report that he read, he read correctly”—gets me to my next point: academic research. If you’re like me, it’s appealing to go straight to the research. After all, how can you get closer to the source? However, after years of getting burned in that arena, I’ve come to be much more careful about how I handle academic papers. First, when it comes to medicine and science, I’m far from an expert, and much of the writing includes language I don’t understand (I spent an hour this weekend trying to wrap my head around what exactly viral shedding is and I don’t feel confident I succeeded). In addition, many studies are carried out on reasonably small sample sizes, which is not a problem in and of itself, but it means that it may not represent the bigger story. This is why systematic reviews like the ones carried out by Cochrane are so helpful.

Finally, and I’ve talked about this a bunch, I find it helpful to keep an archive of the good things I’ve read. I use Evernote for this, though I know others use many different methods. The advantage of a system like this is that it’s easy to go back and find sources when you need them. Your memory is prone to misremembering, an archive isn’t. (NRB)

Game of the Day:

Guess my Word took over WITI Contributor’s Slack for a few days. The rules are pretty simple: guess the word of the day with only clues of whether it’s before or after you word. There’s also a hard version. (NRB)

Quick Links:

Via the always excellent Future of Transportation newsletter, Tesla Remotely Removes Autopilot Features From Customer’s Used Tesla Without Any Notice (NRB)

This New York Times profile of SNL castmember Bowen Yang from a few weeks ago is great. (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Charlie (CW)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).