Why is this interesting? - The Hidden Intentions Edition

On VPNs, the great game, and surveillance masked in utility

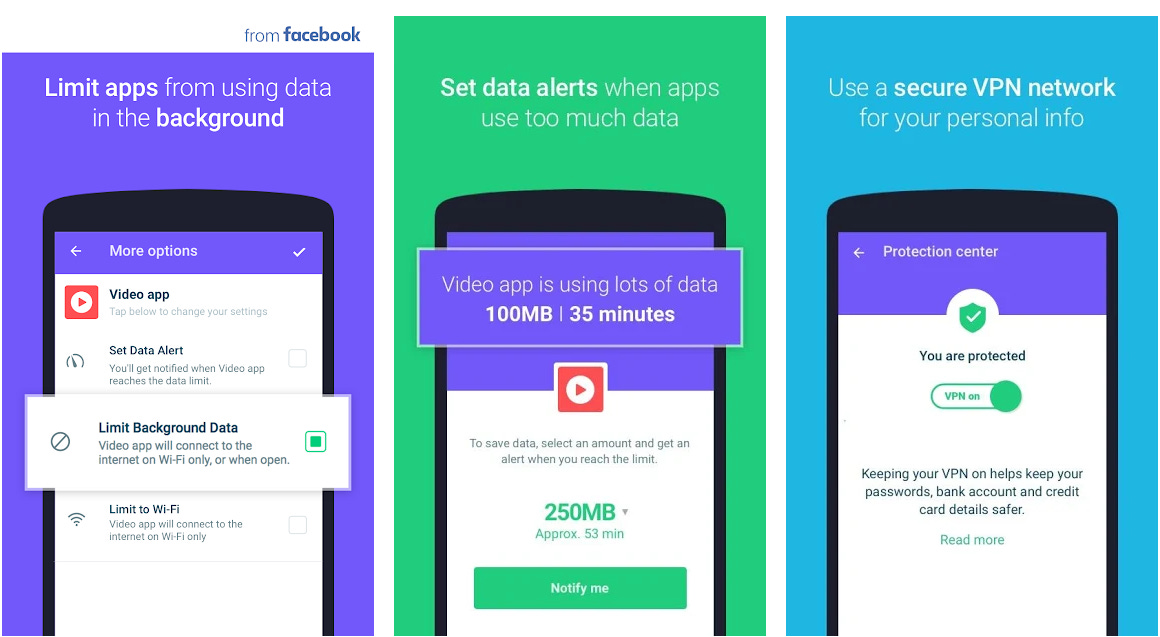

Colin here. Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) have had a fascinating run in the news over the past few years, notably for not being quite as private as promised. Last year it came out that Onavo, a VPN of sorts that made mobile apps to help cut down on data usage and secure your data, was actually (i) owned by Facebook and (ii) being used to quietly examine the mobile apps and user behavior of teens.

According to Techcrunch back in February 2019:

That data revealed WhatsApp was sending over twice as many messages per day as Messenger, BuzzFeed’s Ryan Mac and Charlie Warzel reported, convincing Facebook to pay a steep sum of $19 billion to buy WhatsApp. Facebook went on to frame Onavo as a way for users to reduce their data usage, block dangerous websites, keep their traffic safe from snooping — while Facebook itself was analyzing that traffic. The insights helped it discover new trends in mobile usage, keep an eye on competitors and figure out what features or apps to copy.

I first started using an Onavo product called Extend a long time ago, when recommended by a friend as a way to get more international roaming data when you were abroad. Ostensibly, you could turn it on and, due to the magic of compression, it let you squeeze more data out of your plan. But, in 2013 when the product was acquired by Facebook for $120 million, it evolved into something that was more akin to an intelligence-gathering tool, being used to observe user behavior and inform Facebook competitive and M&A strategy. Quite a leap.

Why is this interesting?

Onavo was a private-sector intelligence coup of sorts that led to a ton of strategic value. Encryption devices and software were in the news in a bigger geopolitical way this week, with a blockbuster Washington Post story. It’s equal parts John Le Carre levels of intelligence intrigue, combined with ample tech and futurism. An excerpt:

For more than half a century, governments all over the world trusted a single company to keep the communications of their spies, soldiers and diplomats secret.

The company, Crypto AG, got its first break with a contract to build code-making machines for U.S. troops during World War II. Flush with cash, it became a dominant maker of encryption devices for decades, navigating waves of technology from mechanical gears to electronic circuits and, finally, silicon chips and software.

The Swiss firm made millions of dollars selling equipment to more than 120 countries well into the 21st century. Its clients included Iran, military juntas in Latin America, nuclear rivals India and Pakistan, and even the Vatican.

But what none of its customers ever knew was that Crypto AG was secretly owned by the CIA in a highly classified partnership with West German intelligence. These spy agencies rigged the company’s devices so they could easily break the codes that countries used to send encrypted messages.

The decades-long arrangement, among the most closely guarded secrets of the Cold War, is laid bare in a classified, comprehensive CIA history of the operation obtained by The Washington Post and ZDF, a German public broadcaster, in a joint reporting project.

The scope, scale, and years of silence that surrounded the program make for an astonishing read.

And perhaps most interesting is how long the program continued due to gummy and slow bureaucracies. According to the article, “...the intelligence kept coming, current and former officials said, in part because of bureaucratic inertia. Many governments just never got around to switching to newer encryption systems proliferating in the 1990s and beyond — and unplugging their Crypto devices. This was particularly true of less developed nations, according to the documents.”

The Post dubbed the project “The Intelligence Coup of the Century,” at least among those we know about. And even though they are two vastly different scales and applications, the two examples of Onavo and Crypto have obvious similarities. And one can’t glance at the recent revelations about Huawei’s alleged backdoor access to the networks it helped build as being very much of the same strategy with even more reach. There are varying motives—from business to politics to intelligence—but the commonality between all these examples is a utility that people desire with masked intent buried deep within the code. (CJN)

Scent of the Day:

Though there are more nuanced and complicated scents, the Hermes classic Eau d’orange Verte always brightens my day a little bit in whatever form: soap, fragrance, etc.. If I had to pick something and stick to it (which is a hard task!) this would be on the very shortlist. Also, fragrance descriptions are amazing. Here’s the writeup from the brand: “The founding cologne, created by Françoise Caron in 1979 and inspired by the smell of undergrowth moist with morning dew, Eau d’orange verte has since asserted itself as an emblem of HERMÈS, standing out by its distinctive freshness. Conceived as an explosion of citrus notes, orange plays the principal role supported by zest and leaves, lemon, mandarin, mint, and blackcurrant bud. The fragrance reveals its complexity in a unique sillage composed of oak moss and patchouli.” (CJN)

Quick Links:

The Chaos at Conde Nast (CJN)

A look inside the Burj al Arab (CJN)

The mattress landfill crisis (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).