Noah here. By all accounts, Donald Rumsfeld was a man who didn’t suffer from a shortage of self-confidence. Whether it was Meet the Press, Errol Morris’s documentary Unknown Known (it’s also worth reading the four-part series Morris wrote on Rumsfeld/the documentary for the New York Times), or a grilling from Jon Stewart on the Daily Show, he always seemed supremely satisfied with his own certainty. Which must have made the public response to what’s become his most famous comment all the more vexing. At a Department of Defense briefing in February 2002, then-Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld was asked about evidence to support claims of Iraq helping to supply terrorist organizations with weapons of mass destruction. “Because,” the questioner explained, “there are reports that there is no evidence of a direct link between Baghdad and some of these terrorist organizations.”

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.

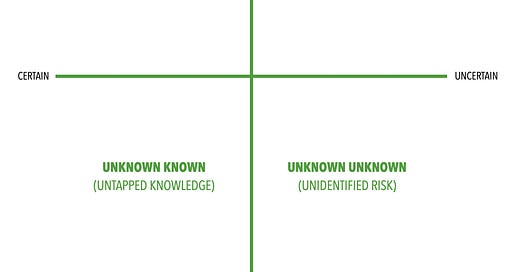

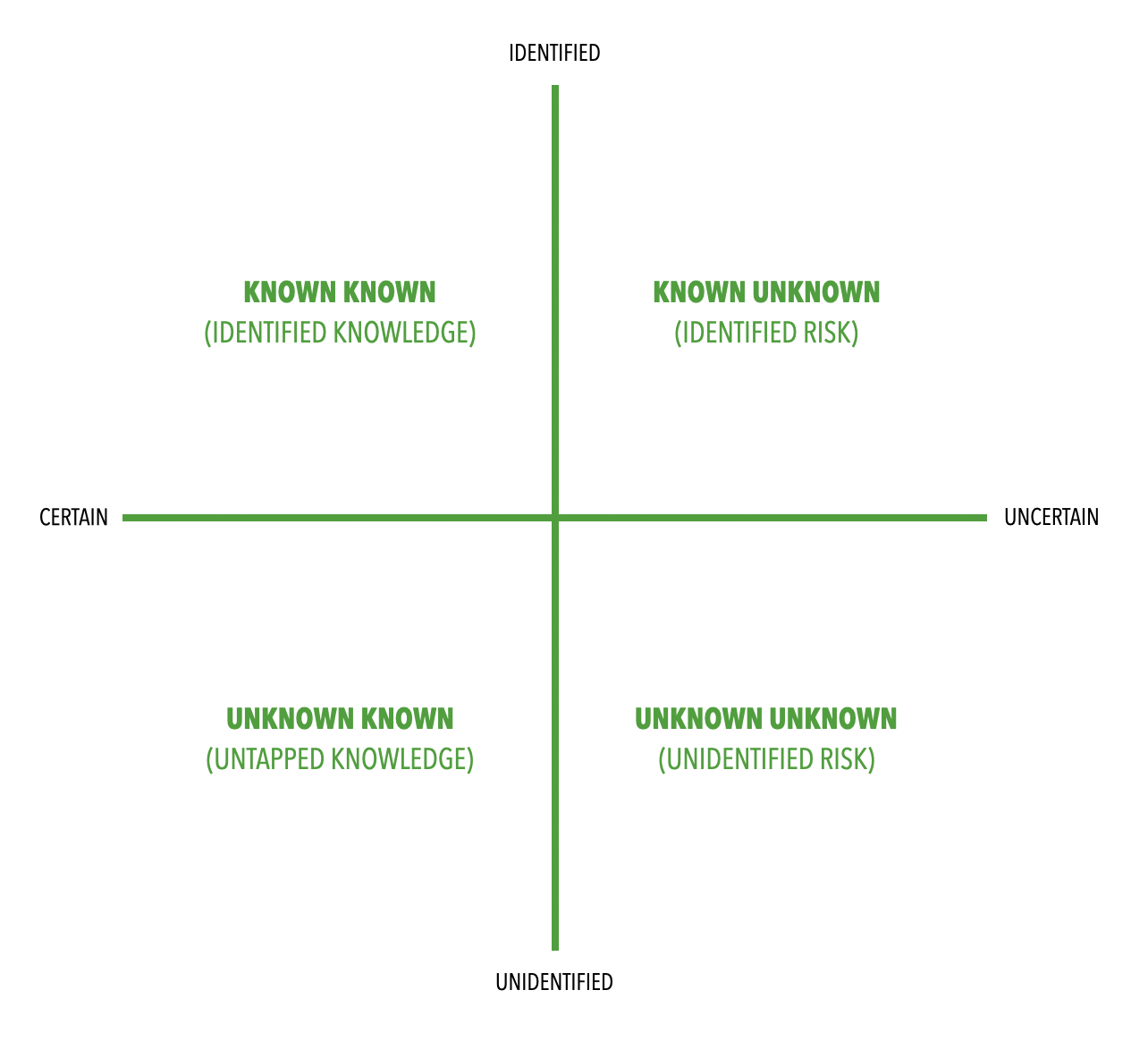

While it’s a mouthful and the context shouldn’t be lost, there’s a useful framework buried in Rumsfeld’s dodge. It looks something like this:

Why is this interesting?

Whatever you might think of Rumsfeld, his logic on this framework was sound and helpful (he didn’t come up with it, by the way, it was in use in the military at least in the 1960s and probably before). “At first glance, the logic may seem obscure,” Rumsfeld wrote in his appropriately titled memoir Known and Unknown. “But behind the enigmatic language is a simple truth about knowledge: There are many things of which we are completely unaware—in fact, there are things of which we are so unaware, we don’t even know we are unaware of them.”

Pearl Harbor (and more recently September 11th) are the canonical American examples of unknown unknowns. Rumsfeld, by his own admission, was obsessed with Pearl Harbor. He specifically quotes from a piece written by game theorist/nuclear strategist Thomas Schelling:

If we think of the entire U.S. government and its far-flung military and diplomatic establishment, it is not true that we were caught napping at the time of Pearl Harbor. Rarely has a government been more expectant. We just expected wrong. And it was not our warning that was most at fault, but our strategic analysis. We were so busy thinking through some “obvious” Japanese moves that we neglected to hedge against the choice that they actually made.

And it was an “improbable” choice; had we escaped surprise, we might still have been mildly astonished. (Had we not provided the target, though, the attack would have been called off.) But it was not all that improbable. If Pearl Harbor was a long shot for the Japanese, so was war with the United States; assuming the decision on war, the attack hardly appears reckless. There is a tendency in our planning to confuse the unfamiliar with the improbable. The contingency we have not considered seriously looks strange; what looks strange is thought improbable; what is improbable need not be considered seriously.

I suspect we’ll spend a good amount of time after the worst of COVID-19 is behind us debating exactly which quadrant of the 2x2 it belonged in. For now, though, I’ve found myself coming back to this 2x2 a lot recently. As we enter this new phase of the pandemic, it seems to me that a lot of the uncertainty lies in that top right box. We have identified a long list of gaps in knowledge—how does it spread exactly? Why do some places fare better than others? Why do some people fare better than others? And on and on—and many very smart people are working day and night to answer them. That doesn’t necessarily change things for our day-to-day, but it feels like it accounts for some of the shifts in conversation over the last few days (less reporting tests, more pontificating about what the future holds). (NRB)

Art of the Day:

From the Saatchi Gallery: “Camera Visual artist, #BeaCamacho, born in the Philippines, and based in USA, focuses on the art of #knitting in her 2005 video #performance piece, ‘Enclosure’.

Bug Channelling her inner caterpillar, she created a cocoon out of red yarn over 11 hours.” (NRB)

Quick Links:

Nick Cave in the excellent Red Hand Files on creating during crisis. Thanks to Zanab for the link. (CJN)

Mr. Latif Peracha has separately made a superb Spotify playlist of lesser known Bad Seeds cuts here (CJN)

The NYC restaurant workers working through the shutdown (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).