Why is this interesting? - The Leveling Up Edition

On sports, competition, and the quest for perpetual enhancement

Emanuel Derman (ED) has written a number of excellent editions for us, most recently The Tetragrammaton Edition. He grew up in Cape Town, South Africa, and came to Columbia University in New York to study for a PhD in physics. Since then he’s lived mostly in Manhattan.

Emanuel here. Though I hardly run much anymore, I recently bought myself a pair of fluorescent-pink Nike Vaporfly shoes (the only color available), the ones in which Eliud Kipchoge broke the world marathon record, though it was not in a genuine race. It was run in a park in Vienna on repetitive laps with very long straightaways and with the assistance of scores of professional pacemakers, an event set up simply to break the world record. The rotation of pacemakers formed a V around him to provide aerodynamic shielding; they knew exactly in which position and at what pace to run by following a green laser beam.

When I read about the shoes, which many other runners, even those under contract to other companies, now seem to use while removing the markings, I thought I would try them. They have a carbon-fiber plate in the forefoot, and when I tried mine, my God, they really do seem to propel you.

Why Is This Interesting?

Roger Bannister ran his first four-minute mile in 1954 on a three-laps-to-the-mile cinder track in Oxford. He was a final year medical student and didn’t do weight training. Now everyone is a professional with a team of trainers, nutritionists, and psychologists and runs on perfect 400m Tartan tracks.

This technological alteration of the event is, of course, the rule rather than the exception. When I was a child we learned to high jump using the “scissors.” If you want to jump over a bar as efficiently as possible, you need to lift your center of gravity the minimum amount. That obviously means you don’t want to jump up vertically to clear the bar, as though you were on a pogo stick—that would require a force to move your center of gravity about twice as high as necessary. Instead, with the scissors, you propel yourself up just high enough that your rear end gets to bar height, and then move your legs over the bar in a scissor-like motion, one blade after the other, so that your legs go over horizontally rather than vertically. Finally, you land in the pit on your feet, one after the other hitting the sawdust.

I say sawdust because that’s what high jump pits used to be made of, and the relative firmness of the sawdust meant you had to land on your feet so as not to injure your body. There was no landing spine-first.

In the early 1960s sports meets started replacing the sawdust pits with scrap foam, which then allowed Dick Fosbury to invent and refine the Fosbury Flop: a method of jumping in which he ran in a sort of J shape towards the bar and then “went over backward, head-first, curving his body over the bar and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump. Because his path over the bar was actually a parabola—the path that Newtonian mechanics dictates for a jumper in the earth’s gravitational field—and because he needed the zenith of the parabola to occur at the position of the bar, he had to take off further from the bar the higher the bar was. This is now pretty much how everyone jumps. Interestingly, he broke a couple of vertebra during the first few years when not all meets had moved to foam yet.

Something similar applied to the pole vault. Eons ago poles were made out of ash or bamboo and then later of aluminum. Now they are made of a mix of metal, fiberglass, and even carbon fiber, which have much greater propulsion energy. Successful or unsuccessful, the vaulters land on their backs, which would be impossible if foam hadn’t replaced sawdust.

Swimming similarly has involved the development of suits that streamline and compress the body. Some really successful suits have later been banned. Pools now have walls that minimize the disturbance and make outer lanes less disadvantageous. Golf clubs and golf balls keep pushing the envelope. Tennis rackets metamorphosized from beautifully constructed Dunlop Maxply multi-layer wood rackets (John McEnroe still used one late in his career) to tubular steel to fiberglass to carbon fiber with larger sizes and sweet spots. “Spaghetti” double-strung rackets that produced a disconcerting spin were quickly banned in the Seventies, a rare retrograde motion. So it goes with almost any sport.

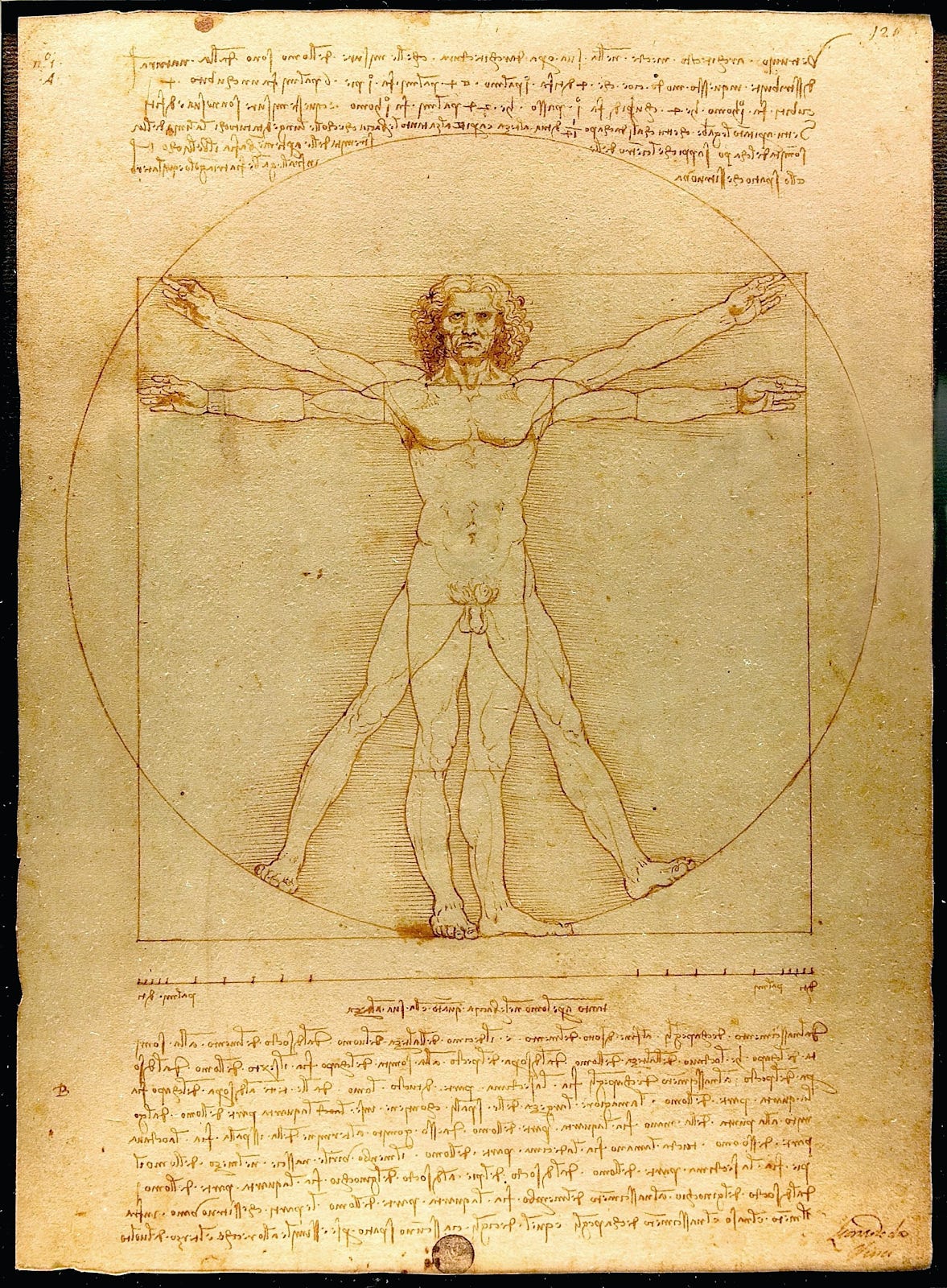

All of this makes it impossible to compare current times, heights, and distances with the past. But there is something appealing about a time-invariant view of the best a human being can be, even though few can hope to achieve it.

I often wish they would have a really pure Organic Olympics with only classic events where the rules are invariant through time: everyone is compelled to compete barefoot on a grass track or field or in a standard pool, wearing only Speedos, and the rules never change and are as close as possible to discounting technological advantages.

I know this is mostly a dream. Where on earth would one draw the line? Doping? Hyperbaric training? Surgery for torn rotator cuffs? Contact lenses? Nutritional supplements? Coffee? People are too complicated and always figure out some way to evade the rules while observing them.

A cautionary example is Limbo 90, a 1952 novel by Bernard Wolfe in which idealistic people cut off their arms and/or legs to protest the nuclear arms race. They want to eliminate the possibility of war by literally ‘disarming’. But technologists invent nuclear powered clip-on brain-connected prostheses that propel high jumpers to 30 meters or more and the Olympic competition between East and West becomes a competition between their technologists. Soon amputation and luxury prostheses become status symbols, and then, in dialectic response, amputation without any prostheses and living helplessly in a basket becomes a selflessness status symbol and a turn-on too.

Still, things do change. You can still find small presses that produce books by hand-press. I know people who homestead and others who knit sweaters out of the wool shorn from their own sheep. Maybe one day? (ED)

Robot of the Day:

This amazing robot bar comes courtesy of interior designer Kelly Wearstler on Twitter (by way of WITI contributor Edith Zimmerman).

Quick Links:

Ben Dolnick on punctuation and culture. “Here’s something I used to think about, back in the before-times: A clause set off by em dashes is like dropping underwater while swimming breaststroke — just a quick dip before popping back to the sentence’s surface. A parenthetical clause is more like diving down to the pool bottom to pick up a coin. And a footnote is a full-blown scuba dive — you have strapped on equipment and left the surface behind and you had better, after going to all that trouble, see something interesting down there.” (NRB)

This newsletter from Surjan Singh outlining “the cultural differences on stiffness” is excellent. (NRB)

More points against fMRI (previously in WITI) (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Emanuel (ED)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).