Noah here. In sports and life, nostalgia is a powerful force. People who recall how tough they had it back in the day are very often wrong. This week some reporters asked New York Knicks basketball coach David Fizdale about his decision to put RJ Barrett, the team’s first-round draft pick and, hopefully, future superstar, back into a blowout game with six minutes left. The coach didn’t take kindly to the question, answering, “We got to get off this load-management crap … Latrell Sprewell averaged 42 minutes for a season. This kid is 19. Drop it already.”

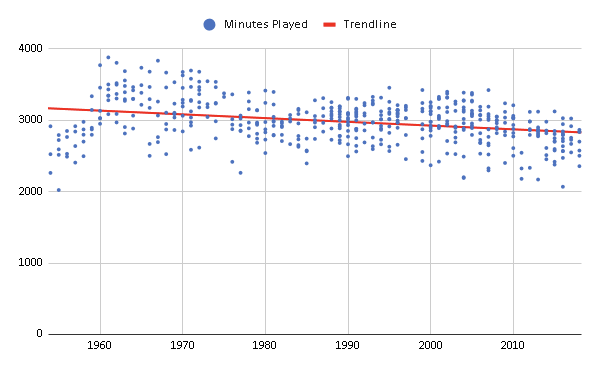

Load management, for the uninitiated, is a term the NBA uses for restricting the minutes of its players. Whereas back in the days of Wilt Chamberlain players would regularly play all 48 minutes, that number has been going down as we’ve learned more about the toll professional sports can take on the human body. I looked around for a bit to find a chart that showed this trend and then just decided to make one myself using data available from Basketball-Reference.com. I grabbed the top 500 NBA player seasons by win shares (a combined metric that tries to get at the impact a player has on winning during a season). As you can see, there’s an obvious trend downward over the last 60 years (the NBA introduced a shot clock in 1954-55):

Why is this interesting?

Stefan Bondy, who covers the Knicks for the New York Daily News tweeted in support of Fizdale on Monday, saying “LeBron James averaged 40 minutes per game in his first five seasons. Tim Duncan averaged roughly the same. Also Michael Jordan. They aged fine. No major injuries late in their careers. Fizdale is right. Load management early in the career is crap.” The fact he chose three of the top ten players in NBA history as his examples aside, there’s a bunch of interesting stuff to unpack about why there’s such a tendency to look back at the past and assume things must have been harder.

Seth Partnow, who used to be a director of basketball research for the Milwaukee Bucks, picked up the conversation, suggesting that Fizdale and Bondy’s view was missing a fundamental difference in the athleticism of today’s game. “The notion that the game is less physical than it was in the (pick imagined golden age) doesn’t stand up to basic scrutiny,” he Tweeted. “Yes players are moving more and faster, further away from [the] hoop. But that’s A) more load there and B) higher velo[city] collisions and such.” The game, in other words, may look less physical, but its most certainly not.

Late 80s/early 90s basketball was filled with legends of physical play. The “Bad Boy” Pistons were famous for how tough they were, even creating a set of rules that specifically dictated how they would guard Michael Jordan. Beyond how to defend him and when to double team, the rules mandated that you had to hit Jordan whenever you got the chance. As then Pistons coach Chuck Daly explained, “any time he went by you, you had to nail him. If he was coming off a screen, nail him. We didn't want to be dirty -- I know some people thought we were -- but we had to make contact and be very physical.” If you grew up a Knicks fan, like me, your version of this came from the hands (and elbows) of guys like Charles Oakley and Anthony Mason.

But the rules changed. The NBA altered the way you could defend, disallowing hand-checking and, more importantly, altering the rules around defensive positioning, making it harder to play the isolation-heavy offensive game that was so popular in the 80s and 90s. As a result of these changes and the birth of the analytics revolution, perimeter play exploded. Because guys today spend more time outside the paint, there’s a widespread belief that the game was far more physically demanding then than it is now. Except that just doesn’t seem to be true and the smartest teams in the league continue to closely monitor minutes throughtout the season. As Partnow put it, “Unless by ‘demanding’ you mean you had to be more ready to literally take a punch, no, the game is vastly more demanding now.” While the NBA may not have the infamous clotheslines of the 1980s, the endless bangs and bumps players receive in heavy pick-and-roll and movement offenses likely have a far bigger impact on their bodies.

While this is ostensibly about basketball, I don’t think it’s hard to extend the metaphor to many other parts of modern culture. First off, in sports as in culture, cross-generational comparisons are always tough. With that said, it's possible to appreciate your cultural predecessors without blindly insisting they were superior in every way. What’s more, nostalgia is a powerful force that can both cloud memories and make one less likely to credit progress that might feel like it takes away from past accomplishments. In this case, I suspect that folks who grew up watching or playing the sport are having their judgment clouded compelling memories. It’s hard to admit that the things that seemed obvious and right to you at one time may turn out to be wrong, partly because it indicates a changing of the guard. (NRB)

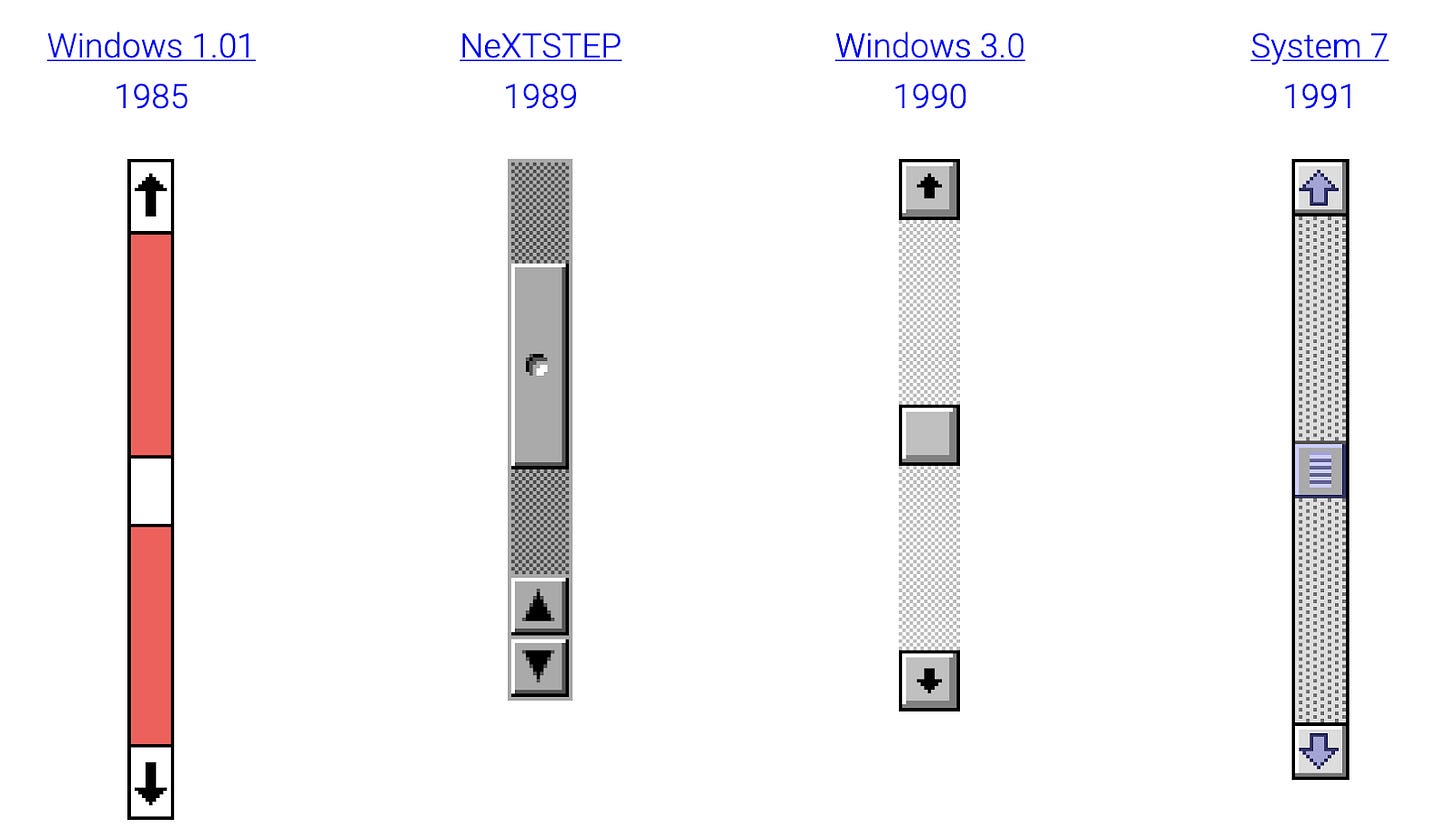

Scrollbars of the Day:

A visual history of the scrollbar from 1981 to 2015. (Via Ana Andjelic) (NRB)

Quick Links:

I can’t write a whole edition about cross-generational NBA player comparisons and not link off to this amazing 12-part series on Dennis Rodman’s insane basketball achievements. (NRB)

How we gather (CJN)

A review of the “Nine Hours” capsule hotel at Narita airport in Tokyo (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).