Why is this interesting? - The New Masses Edition

On the Great Depression, journalism, and different perspectives in history

Jason Boog (JB) is the West Coast correspondent for Publishers Weekly and was previously publishing editor at Mediabistro. He is also the author of The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today.

Jason here. Depression-era America, not unlike COVID-era America, was a terrifying time for writers, artists, and other creatives with already-precarious finances. One magazine captured their sentiment and situation precisely. That magazine was New Masses.

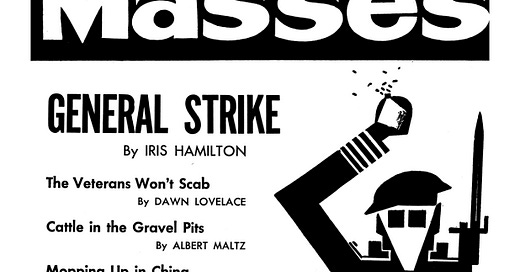

Beginning circulation in 1926, just a year after The New Yorker, and published during the last moment in history when the term “communist” could still hold positive connotations for mainstream American audiences, New Masses was bursting with Communist kitsch, eye-popping art, and great work from writers like Ernest Hemingway, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, and Langston Hughes.

For a few glorious years, New Masses printed manifestos (Are you bored with the prostitute press which feeds you on canned releases cooked up in the propaganda kitchens of Wall Street and Washington?”), grim cartoons (like the one where college kids step off the graduation podium and head straight into a breadline), and Communist classified ads ("Make This a RED CHRISTMAS!)"

Why is this interesting?

The Riazanov Library has mounted the epic task of digitizing the magazine, giving 21st Century readers free access to the New Masses’ digital archives. This free site collects more than 800 issues of the publication, taking us back to a miserable and revolutionary moment in American history.

I consulted this archive weekly while writing The Deep End, because nobody covered the 1930s the way they did. While researching my book, I found a distinct discrepancy between mainstream coverage and New Masses coverage of crucial moments in the Great Depression.

When massive protests broke out in Harlem in 1935 after a young Black boy was detained and beaten at a department store, New Masses published eyewitness accounts of the event, as well as reporting on the repressive and impoverished conditions in the community that led to the unrest (April 2, 1935 issue). In that issue, New Masses described this epic demonstration as a revolutionary turning point in the 1930s, laying out the brutal facts at the heart of the uprising:

“The events in Harlem on March 19 frightened the authorities out of their wits and started a train of activities that may provide a great impetus in the fight of the twelve million Negroes in the United States for freedom ... Why did the beating of one Negro boy set off a popular explosion that ripped open dozens of stores, brought thousands of police to the scene, threw the fear of the proletariat into them to such a degree that they they fired their guns to intimidate the crowd? First of all 65 to 80 percent of Harlem is without jobs. Landlords there are thieves who jack up the rents fully 100 percent to Negro tenants. Harlem is the dumping ground for all inferior food products in the city. The owners of the large stores practice such brazen discrimination that they refuse to hire Negro workers.”

The New Yorker barely even blinked during those same tumultuous months. According to my keyword search through the digital archives, The New Yorker only mentioned Harlem four times throughout 1935. In the days after the Harlem uprising, the magazine published a breezy shout-out to Morris Ernst, the crusading attorney who joined the city’s Commission on Conditions in Harlem and helped write a government report on the suffering and discrimination endured by Harlem residents. In 1936, New Masses would publish a leaked copy of that commission’s report, giving the news top billing on the magazine’s front cover (July 14, 1936).

In contrast, The New Yorker ran a single “Talk of the Town” paragraph praising Ernst for his work that ends with a condescending and cringe-worthy joke about upper-class parents “quelling a riot in the nursery.”

“To be a person of liberal tendencies in these times must be extremely trying—there is so much to be done. We are thinking of a person like Morris Ernst, the liberal barrister, who is called upon to serve the community in every calamity, and who does. When taxi-drivers grow disgruntled, Mr. Ernst is invited to bargain with them. When a fine book is branded obscene, Mr. Ernst is elected to defend it against censors. When a birth-control clinic is raided by a snoopy police woman, Mr. Ernst turns up in court, champion of freedom. When Harlem erupts, the mayor of the town looks around for a liberal man, and there is Mr. Ernst. Such a man amazes us—us whose liberal tendencies are exhausted by 9 A.M. in simple home matters such as defending a puppy against a cook or quelling a riot in the nursery.”

Alongside this commentary, The New Yorker ran an ad full-page advertisement with sketches of women wearing French lingerie. One silky offering cost $95, which translates to around $1,820 in 2020 dollars. “We urge you to see the rest before you complete your spring wardrobe plans,” gushed the ad placed alongside a snickering piece about how a starving community had the bad manners to “erupt.” In October 1935, The New Yorker’s final mention of Harlem during that bleak year, the Talk of the Town ran a brief “Anthropological Item” with monstrously racist implications.

“A horrid piece of news comes from the Harlem Branch of the Public Library. A little colored girl-not a day older than Shirley Temple - asked for, and was given a book on cannibalism. She took it away with her. That’s all our informant knows about it. That’s all we know.”

In a very literal way, the New Masses subscriber base threatened to overthrow the bourgeoisie readership of The New Yorker at this juncture in history. The Communist Party counted 30,000 members in the United States in 1935, and Depression-era evangelism stoked membership to 80,000 in 1944. At the height of this radical explosion in the 1930s, the circulation of the New Masses surged past 100,000 copies—the peak print run of its entire life as a magazine.

New Masses covered the suffering and anger simmering beneath the headlines of the mainstream press, routinely antagonizing the ruling class that kept these emotions out of newspapers and magazines. New Masses also reported on the alarming rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the South, the struggles of farmers in Mexico, and Hitler’s earliest atrocities in Germany. Between 1930 and 1935, they told the stories of hundreds of thousands of people who lost their jobs and thousands of families that were evicted from their homes. Unemployment peaked at 25 percent and the streets filled with hungry and angry people.

“Hungry people don’t stay hungry for long,” goes the old Rage Against the Machine song, reminding us how hard times can kindle radical solutions. Economic recovery requires many years of turbulence, but New Masses shows us how the blast furnace of the Great Depression forged some of the New Deal’s most creative initiatives: the Federal Writers Project that put thousands of writers back to work and the Federal Arts Project that painted murals around the country. I can’t help but wonder, what sorts of things will we be reading in 2025? What sort of crazy solutions will we find?

A Pink Floyd-esque New Masses cover from the July 24, 1934 issue

A New Masses cartoon from the May 8, 1934 issue

Classified Ads from the March 13, 1943 issue of New Masses

(JB)

Cartoon of the Day:

A cartoon printed in the April 30, 1935 issue of New Masses, the perfect inversion of a New Yorker cartoon. (JB)

Quick Links:

The text-based video game AI Dungeon has updated with GPT-3, the supercharged version of Open AI’s language model that can imitate human writing styles. An AI-generated never-ending story. (JB)

“History works like science fiction: We want to know who did what and why they did it, even if we know who wins in the end." Wired magazine looks at Afrofuturism as a guide through the chaos of 2020. (JB)

Darius Kazemi explains how and why you should make a small social network for you and your friends.

I can’t stop thinking about what poet Ocean Voung said about the yin/yang of creativity, so effortlessly explained during a Q&A period.

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Jason (JB)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).