Why is this interesting? - The Online Grocery Edition

On delivery, groceries, and the e-commerce surge

Dan Frommer (DF) is a longstanding friend of WITI and has graciously shared an astute post from his main gig, an essential business newsletter called The New Consumer. You should join! He also writes Points Party, a newsletter about credit cards and travel points and has wonderful taste in cities and restaurants. - Colin (CJN)

Dan here. While “social distancing” at home this past week to help slow the spread of Covid-19, one of the few feel-good—or at least feel-normal—experiences was being able to successfully order groceries online and receive them just a few hours later via (greatly appreciated) Amazon delivery workers.

But even beyond the obvious privilege, I feel like one of the lucky ones: a quick Twitter search reveals many frustrated shoppers, widespread problems with orders and deliveries, few available delivery windows, and overloaded customer service departments.

Why is this interesting?

Online grocery shopping was built for convenience, and in normal times, functions pretty well that way, still handling a small percentage of overall grocery spending. But as US cities shut down, and as tens of millions stay home to help “flatten the curve,” grocery delivery has become essential infrastructure. And as demand spikes, it’s showing its cracks.

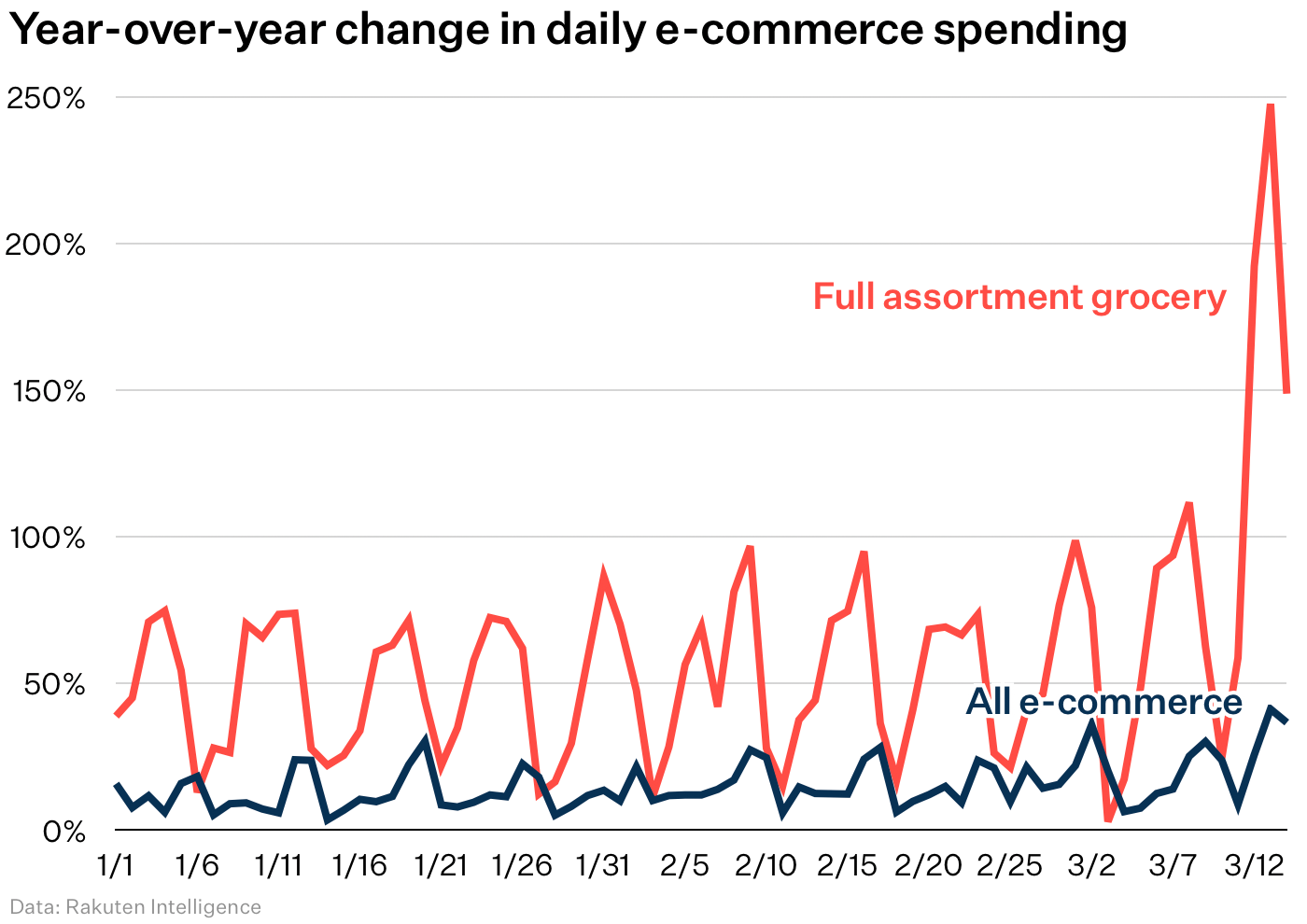

Overall, through March 15, online grocery spending in the US had been growing around 60% year over year, according to Rakuten Intelligence, faster than the nearly 20% overall growth in e-commerce spending.

But over the past two weeks, as Americans stocked up to stay at home, those numbers spiked. Over the span of March 12 through March 15, online grocery orders grew more than 150% over the same period in 2019, while spending grew 210%, reflecting larger average orders, according to Rakuten.

(The broader US e-commerce numbers are up, too: overall e-commerce spending was up about 36% year over year from March 12 through March 15, according to Rakuten. That’s almost twice the growth rate it had been generating this year.)

And more new customers are taking their grocery orders online, using services like Prime Now and Instacart, which offers grocery delivery from more than 5,500 cities. (My mobile analogy: If Amazon is building the vertically integrated “iPhone” of online grocery, Instacart is the Android, powering e-commerce and delivery for more than half of US and Canadian grocery stores.) Instacart was roughly the 40th most popular free iPhone app in the US over the weekend, according to App Annie, up from its usual rank around no. 400.

This spike in demand—not to mention anxiety around worker health, which should be a primary concern—has seriously strained the system.

First and most obvious, it has quickly become a challenge to place orders—unpredictable and unreliable.

Availability for Instacart varies by ZIP code and store. In some queries, delivery is available within two hours. But in others, either not for several days, or none at all. At Good Eggs, a gourmet online grocer in the Bay Area, today’s customers are already ordering for next week—other delivery days are sold out.

The problem is that many of these services seem to be designed entirely around those timed delivery slots. In part, that’s an attempt to match supply—available “shoppers” and delivery drivers—with demand. But also because in normal circumstances, the user’s priority is receiving delivery during a specific, convenient time slot, such as when they’re home from work.

(Amazon’s Prime Now service, which powers delivery for Whole Foods, also has a unique design flaw: you can’t even see available delivery slots until you’re in the checkout flow. So there’s a risk of taking the time to fill your basket, only to find out that you can’t actually get the food you want because there are no open slots. I’ve seen several complaints about this. My tip here is that slots seem to open and close all the time—fill your cart and refresh often for slots that may have opened.)

Then, getting what you actually need or want is also proving tricky. At Whole Foods, there’s a limited selection that seems to change every time I try to place an order. Other grocers have clearly never taken online shopping seriously, and have improvised storefronts through point-of-sale software, half-baked e-commerce sites, or my favorite, the Union Market plain-text field.

This is not the time to nitpick about user interfaces. We are likely going to have to survive with the status quo for the next few months and should appreciate the risks that everyone is taking to keep the system moving. The good news is that the food supply chain seems to be fine, at least for now, with distribution as the bottleneck. And Instacart just announced that it plans to hire 300,000 more workers, which will help. Amazon wants to add 100,000.

But this seems the sort of singular event that will drive real change. While the recession we’re entering will have its own effects on the trajectory of e-commerce spending, I expect an upward inflection point in the adoption of online grocery shopping. Grocers large and small will have to figure out systems that work.

One feature I propose would be a sort of “surge mode” for high-demand periods where convenience is less of a priority and essential sustenance is the goal.

In this mode, grocers—or even an aggregated service operated by Instacart—could offer a master queue, so customers could order what they need and have it delivered whenever possible, not just during a narrow time slot. Many people are at home all the time right now, so this would go far toward alleviating stress and perhaps even helping more efficiently route deliveries over the course of a day.

Another “surge mode” feature that seems obvious right now is some way to prioritize orders for those in greatest need or danger. This would involve some compromise in privacy and might be tricky to police. But for example, several grocery chains, including Whole Foods, are now providing an hour for seniors to shop before opening to the general public. Offering a similar priority mode for online delivery would be ideal.

The best case is that by the time we’re experiencing a similar public health catastrophe, we’ve moved well into the next era of grocery, with automated warehouses and delivery models. But for now, empathy and persistence seem our best tools while relying on a system that simply wasn’t built for this. (DF)

Architects of the Day:

It’s worth perusing the portfolio of Japanese interior design firm Wonderwall. Everything is super crisp, and they’ve designed so many iconic shop spaces in Tokyo and elsewhere that their aesthetic feels part of the urban fabric. According to Designboom, “with standout interiors for Thom Browne, A Bathing Ape, Uniqlo, and Diesel, collaborations with Jasper Morrison, Pierre Hermé and Pharrell Williams, Katayama has changed the way we think about the consumer experience.” His contribution to the field is summed up neatly by MoMA’s Paola Antonelli in the book Wonderwall Case Studies: works by a global interior design firm: “Like very few other designers in recent history…Katayama has defined the 1990s and 2000s and changed the world of interior and retail design.” (CJN)

Quick Links:

How the Pentagon became Walmart via Brady M. (CJN)

The Untold Story of MBS on Fresh Air (CJN)

Longread on the ascent of Glossier (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Dan (DF)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).