Why is this interesting? - The Oral Culture Edition

On words, objects, and how to build cultures that endure

Today’s edition is from Lizzie Shupak (LS). She is Co-Founder of Curve, a London-based creative leadership and culture change business. She works with senior leaders around the world to facilitate change. Her background is in innovation and digital service design and did a stint as a visiting researcher at Columbia University’s Institute for Economic Research and Policy, where her focus was semiotics and military ethics education.

Lizzie here. Earlier in the year, Noah posted an edition that referenced Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy and discussed the ways in which language impacts understanding. It reminded me of an HBR article written a few years ago titled The Unintended Consequences of Diversity Statements, which explored the impact of companies’ diversity statements on their ability to recruit and retain diverse talent.

In trying to address discrimination, many organizations now explicitly advertise their dedication to diversity, identifying themselves as “equal opportunity” or “diversity-friendly” employers. The thinking, presumably, is that such statements will increase the diversity of their applicant pool and ultimately of their workforce. We know a lot about how effective these diversity statements are, and, unfortunately, the answer is “not very.” They can even backfire by making organizations less likely to notice discrimination.

This piece came out back in 2016, and since then, the push for organizations to explicitly communicate their positions on diversity and inclusion, as well as other things like sustainability and purpose, seems only to have increased. Change by Powerpoint is, I find, as pervasive as ever.

Why is this interesting?

There is a paradox between what appears to be a genuine desire for transformation in organizations, and, to paraphrase Anand Giridharadas in Winner takes All, the fact that “Powerpoint is the technology of the status quo.” For all the talk and financial investment in real-world change, the default medium remains words and frameworks typed on slides.

Science writer Dr. Lynne Kelly, in her book The Memory Code, introduces the idea of memory spaces: songlines and physical artifacts used by indigenous communities throughout human history as ways to encode enormous amounts of information. Such cultures have been able to maintain encyclopedic quantities of knowledge about plants and animals, land usage and management, rules and morality, and a huge number of other areas by attaching stories, songs, performance, and ceremony to specific objects (Lukasa memory boards used by Luba elders in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo), environments (the 5.5 mile base of Uluru in Central Australia), and monuments (Stonehenge in the UK). As Kelly explains:

By repeating the stories of the mythological beings through songs and dances at sacred landscape sites, information could be memorised, even if it was not used for tens, hundreds or thousands of years. Songs are far more memorable than prose. Dances can depict animal behaviour and tactics for the hunt in a way no words can do. Mythological characters can act out a vivid set of stories that are unforgettable.

The ancient Greeks used a similar technique, the “method of loci” to mentally walk through familiar physical environments in order to memorize their speeches. The use of objects, physical environments, stories, and songs as technologies to store data, has proven to be a scalable and sustainable strategy, despite being seen as inferior by Western leaders in both business and civil society. “What astonishes me,” Kelly writes, “is that these memory skills were allowed to fade from the Western education system during the Renaissance and are today used only by a smattering of people keen to memorize the order of shuffled decks of cards for competitions.”

In prioritizing the written word as our means to preserve knowledge, we have lost some of our capacity to communicate. It’s not that writing doesn’t serve a great purpose, but that the tradeoffs—of emotion, of interaction, of experience—are too often overlooked. Kelly again:

In documenting the songs containing extensive knowledge of over a hundred plants used by the Australian Yankunytjatjara people from the remote northwest of South Australia, the translator noted that ‘in written form the stories lack the performance quality that was so much a part of the way they were told.’

I think this could usefully impact the way that we think about culture creation and culture change within organizations. Tech humanist Kate O’Neill talks about culture as being “interactions at scale”, which is, perhaps, a helpful provocation to prevent us from spending time and energy on crafting written statements of intent. It’s very easy to feel like the job is done when the words are written. I’d suggest seeing the words as simply one element of a bigger picture, a picture that is primarily concerned with behavior and action. What if, as well as thinking about beautiful digital documentation, we also think more deeply about how people experience their physical environment and how we might encode meaningful information within it. (LS)

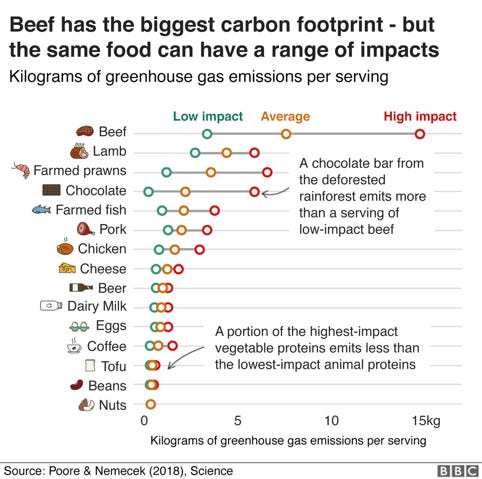

Chart of the Day:

(LS)

Quick Links:

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Lizzie (LS)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).