Why is this interesting? - The Patchwork Pandemic Edition

On cities, COVID, and cognitive dissonance.

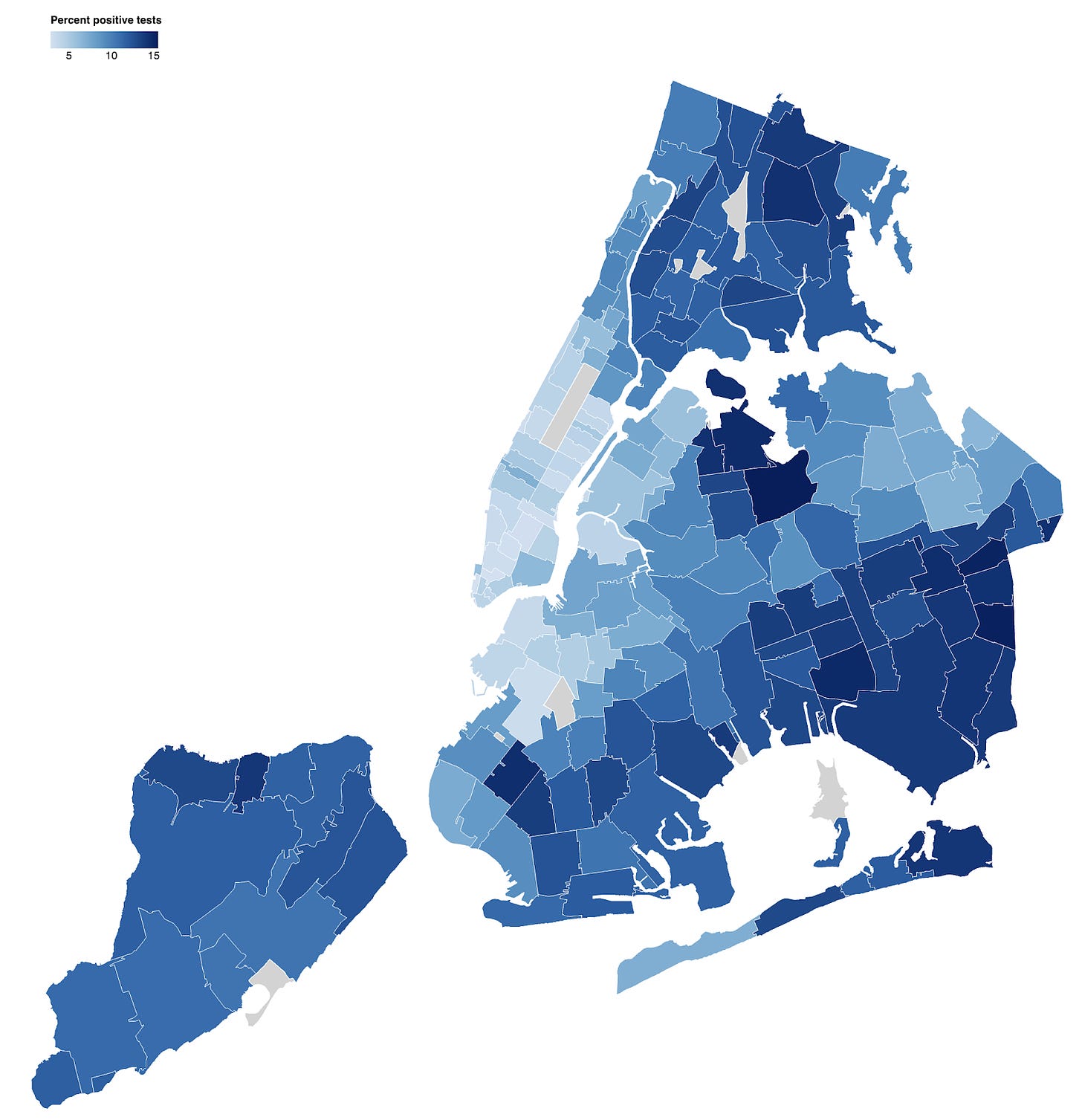

Noah here. This week the Mayor of New York City announced that they were going to start rolling back openings in nine zip codes across the city that had particularly high COVID rates. This meant stopping in-person school and closing non-essential businesses, including cutting off indoor and outdoor dining at local restaurants. The governor, who has ultimate authority over these things, announced on Monday that for the meantime he wouldn’t be moving forward with closing businesses, explaining that “A ZIP code is not the best definition of the applicable zone.” He then followed it up with some confusing maps and passive-aggressive PowerPoint slides.

Why is this interesting?

One of the things that has been rattling around in my brain a lot over the last few months is how local this virus, and the policy we use to prevent it, has become. Without much in the way of national guidance, states and cities are left to find ways to slow the spread. To some extent, that makes sense: so much of how we deal with the virus is dependent on how prevalent it is in a specific area. In New York State, like much of the rest of the country, reopening was pegged to a number of factors that included a 7-day rolling average of a sub-3% test positivity rate. The explicit acknowledgment there was that we shouldn’t look at the state as a whole, but rather focus on the levels of virus in a specific locality to understand whether it was safe to start unwinding our March-level lockdowns.

The problem with this is it creates a very strange cognitive dissonance when we engage with national conversations. A call to a friend in another state about school openings can easily turn heated, with strong opinions from both sides. What at first seems like a fundamental disagreement in approach, though, ultimately turns out to be two very different reactions to specific local conditions. In other words, many of the most serious proponents of in-person schooling live in areas where the virus is currently under reasonable control while the opponents are dealing with rising levels in their locales. Both sides feel justified in their approach, which can create a confusing situation until you unwind the argument from those local statistics.

Similarly, this makes national news about COVID hard to square. While it’s obviously important to keep statistics at the national level, it’s hard to always find your local story told within them. Those in Texas, for instance, were able to largely keep living their lives in March as the virus ravaged New York. As New York improved in May and June, other cities and states saw rising levels. I’ve found myself mostly skipping national virus coverage for the work of local news organizations like The City here in NYC, who are covering the on-the-ground reality of my life much more meaningfully. This is even more true when looking at stories of how other countries, which have different conditions and virus levels, are handling their own unique situations.

In May, Ed Yong, who has done a tremendous job covering COVID, called it a “patchwork pandemic.” Here’s how he explained it:

A patchwork pandemic is psychologically perilous. The measures that most successfully contain the virus—testing people, tracing any contacts they might have infected, isolating them from others—all depend on “how engaged and invested the population is,” says Justin Lessler, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins. “If you have all the resources in the world and an antagonistic relationship with the people, you’ll fail.” Testing matters only if people agree to get tested. Tracing succeeds only if people pick up the phone. And if those fail, the measure of last resort—social distancing—works only if people agree to sacrifice some personal freedom for the good of others. Such collective actions are aided by collective experiences. What happens when that experience unravels?

“We had a strong sense of shared purpose when everything first hit,” says Danielle Allen, a political scientist at Harvard. But that communal mindset may dissipate as the virus strikes one community and spares another, and as some people hit the beaches while others are stuck at home. Patchworks of risk and response “will make it really hard for the public to get a crisp understanding of what’s happening,” Rivers says.

While going down to the zip code level of the patchwork is a natural conclusion, it makes me feel very uncomfortable. We know that this virus has already attacked communities in an incredibly uneven way, but at least we’ve all largely been governed by the same set of policies, whether we agree with them or not. As we make this final shift to zip-, neighborhood- or even street-level enforcement, it runs the real risk of pulling on that last small sense of shared purpose we have. While I absolutely believe we need to deal with these issues as and where they occur, I can’t help but worry about what happens to a city as it splits into ever more hyperlocal segments. (NRB)

Speaker of the Day:

I’ve always spent a lot of time in headphones, but they are now unavoidable in every facet of the day. To mix things up, I recommend this small, portable speaker from Bang and Olufsen. It is small, portable, sounds amazing, and travels well. There’s something nice about hitting the road with it: setting up a little listening rig in a hotel room, where the music has some space to bounce around and breathe. It is also very nice for conference calls via Bluetooth, should you want to break the monotony of your Airpods. Highly recommended. (CJN)

Quick Links:

Roger Penrose won the Nobel Prize in Physics this week “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity.” One of his more controversial theories is that consciousness is a result of quantum phenomena. (NRB)

One day I’m going to get around to writing a microbiome edition … From Ars Technica: Archaeologists delved into medieval cesspits to study old gut microbiomes (NRB)

Apple Watch 6 has blood oxygen detection. Apparently, it doesn’t work very well. (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

PS - Noah here. My company, Variance, is looking for a lead product designer (remote) to join the team. If that’s you or someone you know, please be in touch.

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).