Perry Hewitt (PH) brings modern marketing and digital product practices to mission-led organizations. Previously CDO at Harvard University, she now consults to organizations including Bloomberg Philanthropies and The Rockefeller Foundation.

Perry here. In the midst of COVID-19’s one-two punch of human tragedy and global economic crisis people are struggling for survival—and meaning. Here in New York City, the challenge is first practical: those fortunate enough to stay at home are figuring out groceries and Zoom calls and childcare. Those deemed essential workers, from sanitation crews to cardiologists, are navigating overcrowded subways and frightening PPE shortages. A physician pointed out to me recently that she had been wearing the same mask for nine days, both in and out of the COVID wards. With all this necessary emphasis on our basic needs, where does the search for meaning fit in, and what role does the arts play?

One argument for the impact of the arts is witnessing the pent-up demand, evidenced not only by indicators like ebook downloads (thanks, NYPL!) and Netflix traffic, but by the social media popularity of art relevant to our current condition. A friend alerted me a couple of weeks ago to a poem by Alexander Pushkin making the rounds online. The poem was written when Pushkin was quarantined at his family estate of Bolshoye Boldino during a nineteenth-century cholera outbreak across Russia. And in 2020, this poem spread across Russian-speaking social networks like wildfire. The style and cadence were recognizably Pushkin, which thanks to a nation of centralized education and a tradition of declamation was familiar to millions of people. And obviously Pushkin’s eloquent description of his time in quarantine speaks to today’s challenges—at least to those privileged enough to #StayHome.

Here’s what was going around as translated by Google:

Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, being in quarantine about cholera in Boldino, addresses

to us today !!!

***

Excuse me, the inhabitants of the country,

In hours of mental torment

Congratulate you from confinement

Happy Great Spring Festival!

Everything will settle down, everything will pass

Sorrows and anxieties will go away

Smooth roads again

And the garden, as before, will bloom.

To help the mind,

Sweep the disease by the power of knowledge

And the days of hard trials

We’ll survive one family.

We will become cleaner and wiser

Not surrendering to the darkness and fear,

Perk up each other

We will become closer and kinder.

And let the holiday table

We will enjoy life again

May the Almighty send on this day

A piece of happiness in every home!

A.S. Pushkin 1827

Why is this interesting?

The poem wasn’t written by Pushkin.

Today, the spread of misinformation on the internet is a common and dangerous reality, rather than something particularly notable or interesting. But three things stood out for me: the idea that a ~200-year-old poem would appeal to and be shared by so many, the trouble someone took to make such a respectable fake, and the question of ferreting out imitation art.

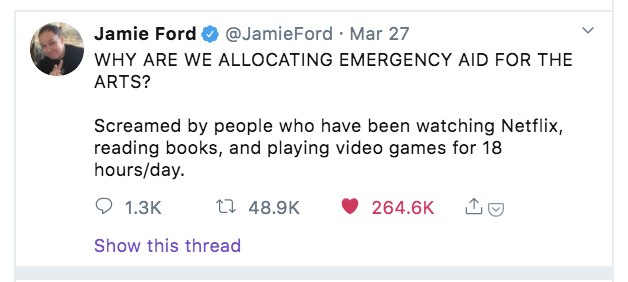

To the first point: it’s reassuring that the arts are helping people make sense of their current reality. Sure, we need The Last Dance and jigsaw puzzles, but literary and historical context can provide a deeper level of comfort and connection. The popularity of streamed performances like the Met Opera’s At-Home Gala and the National Theatre’s plays reveal that pent-up demand—as does the social spread of the faux Pushkin. We can both attend to people’s basic needs as the coronavirus persists and the economy suffers, and also recognize the power of art forms like poetry that “can jolt our minds into thinking … in unexpected ways.”

Secondly, the skill and effort it took to make such a high-quality imitation is fascinating: the style, rhyme, meter were all close enough to pass for many readers, including the prominent economist and writer Alfred Koch—who is said to have posted it on his Facebook page. There were a number of tells for those paying close attention—a few in the verse, and a big one in the 1827 dateline (Pushkin was quarantined at Boldino in the fall of 1830). Was it written as a mockery of that longing for the literary canon to tell us this global pandemic, too, shall pass? Or just as an exercise to see how far a fake could travel?

Who did write the fake quarantine poem? Some attribute it to a Kazakh writer, who posted the verse on March 21. Others believe it to be the work of Maryan Belenky, a Ukrainian Jewish writer and translator who now lives in Israel, and several years ago admitted to writing a fake Mayakovsky poem that made the rounds.

Finally, how perfidious is a fake poem? Verse falsely attributed to Pushkin has circulated for centuries: part homage, part cunning. On the one hand, made-up news across social networks is dangerous, and even threatens democracy. Is fake art a similar breach of trust, and even more pernicious during a crisis? Or is it harmless fun to make people feel comforted and connected, and only mildly duped when the sham is revealed?

The tale of the fake Pushkin provided me with a welcome distraction in this time of “social distancing.” I’ll let the real Pushkin have the last word. On September 30, 1830, Pushkin wrote to his fiancée Natalia Goncharova: “I’ve been notified that there are five quarantine zones set up from here to Moscow, and I will have to spend 14 days in each. Do the maths and imagine what a foul mood I am in!” (PH)

Playlist of the Day:

We love the work of Orchid Music Design. They put together playlists for spaces, and do an exceptional job at it. Here’s a playlist of the music they program at some very interesting hotels, including the Hotel Saint Cecilia in Austin, and El Cosmico in Marfa. (CJN)

Quick Links:

Virtual tours of iconic skyscrapers (CJN)

On decadent self isolation (CJN)

Chile oil is so hot right now (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Perry (PH)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).