Why is this interesting? - The Reach vs. Influence Edition

On reach, influence, and the confusion between the two

Noah here. Earlier this week Colin wrote a piece about influence and influencers that seems to have struck a nerve with a bunch of you. Over the years I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about and researching this kind of marketing influence and I thought it would be worth expanding on the topic a bit.

As far as I can tell, most of the popular conversation around influencers really got started with Malcolm Gladwell’s Tipping Point. The book starts with the story of Hush Puppies, a brand left for dead that saw a sudden resurgence:

How did that happen? Those first few kids, whoever they were, weren't deliberately trying to promote Hush Puppies. They were wearing them precisely because no one else would wear them. Then the fad spread to two designers, who used the shoes to peddle something else - high fashion. The shoes were an incidental touch. No one was trying to make Hush Puppies a trend. Yet, somehow, that's exactly what happened. The shoes passed a certain point in popularity and they tipped. How does a $30 pair of shoes go from a handful of downtown Manhattan hipsters and designers to every mall in America in the space of two years?

While at no point does he mention influencers, the book kicked off a shift in digital marketing towards “viral” and the idea that finding just the right person could be the key to seeing your brand plunge over the tipping point from niche to mass appeal. To be fair to Gladwell, he doesn’t say this precisely. The broad point of the book is that there seem to be three key characteristics that make things (ideas, viruses, brands) grow: “one, contagiousness; two, the fact that little causes can have big effects; and three, that change happens not gradually but at one dramatic moment.”

Why is this interesting?

Like lots of ideas in marketing, a grain of truth was churned into a pearl of hype. After the tipping point, every brand was sure that finding one influencer was the key to them going “viral”. The problem? This isn’t really how it works. Or rather, it doesn’t work this way predictably. This is one of those ideas we struggle with because we all experience influence in our daily life. The one friend who’s book recommendations we always take is different than the friend with great musical taste. Their influence over us is indisputable, so why wouldn’t this be true for broader culture? Well, it’s not that it isn’t true, it’s that it can’t be predicted at scale.

Let me explain. The base of the “influencer” idea from the Tipping Point is that if you find a few hyper-connected people they can help push your brand over the edge. The problem is that the data doesn’t back that up. Duncan Watts, a network scientist who has been doing research in this space for 20+ years has shown this over and over again in his research. Here’s Clive Thompson writing for Fast Company about Watts and his ideas in 2008:

In the past few years, Watts–a network-theory scientist who recently took a sabbatical from Columbia University and is now working for Yahoo –has performed a series of controversial, barn-burning experiments challenging the whole Influentials thesis. He has analyzed email patterns and found that highly connected people are not, in fact, crucial social hubs. He has written computer models of rumor spreading and found that your average slob is just as likely as a well-connected person to start a huge new trend. And last year, Watts demonstrated that even the breakout success of a hot new pop band might be nearly random. Any attempt to engineer success through Influentials, he argues, is almost certainly doomed to failure.

What came out in the research is not that fame comes miraculously from one hyper-connected individual, but rather that it requires a nearly perfect storm of factors to break through. As explained in Watts’ 2007 paper “Influentials, Networks, and Public Opinion Formation”, “large scale changes in public opinion are not driven by highly influential people who influence everyone else, but rather by easily influenced people, influencing other easily influenced people.” To that end, when Watts did original research into how music spreads through a social network he found that the only reliable signal for what would hit and what wouldn’t was popularity. The rich get richer, as the saying goes.

So have all these brands been hoodwinked? Kind of, but not exactly. While influence may not be a predictable way to spread a marketing message, reach certainly is. Most of what passes as metrics of influence, specifically follower counts, is simply the case of mislabeling. Getting an Instagram post by someone with a large following can certainly have huge value for a brand. And that value can be multiplied if the brand is in an industry associated with the person posting it, meaning it will likely also be of interest to the audience. How do we know this works? Because it’s been the business model of all media for 100 years: Attract an audience by creating content that they find worth consuming and sell access to that audience to brands who want to reach them. When you think about influencer marketing as no different than reach-focused advertising you can do apples for apples comparisons. In that case it’s not about whether that influencer sold any shoes or hotel rooms, but rather about the cost per impression and the impact of that spend. (NRB)

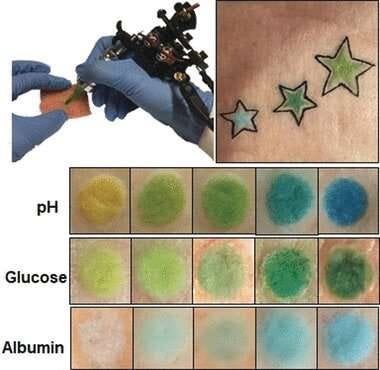

Tattoo of the Day:

This is pretty cool. “The art of tattooing may have found a diagnostic twist. A team of scientists in Germany have developed permanent dermal sensors that can be applied as artistic tattoos. As detailed in the journal Angewandte Chemie, a colorimetric analytic formulation was injected into the skin instead of tattoo ink. The pigmented skin areas varied their color when blood pH or other health indicators changed.” (NRB)

Quick links

I recently interviewed the founder of Brightland (featured in WITI here) in LeanLuxe. (CJN)

The Fed keeps calling peak employment wrong. (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)