Why is this interesting? - The Rivers Edition

On the United States, geography, and geopolitics

Noah here. There was an aside in a New York Times article from early 2017 that sent me down a fascinating rabbithole. Here’s the paragraph (emphasis mine):

The United States, occupying as it does the temperate zone of North America, is the most consequential “satellite” of the Afro-Eurasian “World-Island,” wrote the British geographer Halford J. Mackinder in 1919. Not only was America physically isolated from the threats and complexities of the Old World, and not only is it abundantly rich in natural resources from minerals to hydrocarbons, but America claims more miles of navigable inland waterways than much of the rest of the world combined. And this river system is not laid over the sparsely inhabited and thinly soiled Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, but over America’s arable cradle itself: the nutrient-rich soil of the Midwest, thus unifying the centers of population in the 19th century, and perennially allowing for the movement of goods and produce in the interior continent. This river system, like the veining of a leaf, flows into the Mississippi, which, in turn, disperses into the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, thus connecting farms and cities throughout the densely habitable part of the United States with the global sea lines of communication.

I initially read it in the Sunday paper and out of sheer chance (I think I had to go do something and hadn’t finished it), I opened it on the web to discover that “more miles” had a delicious blue link waiting for me. If you click through, as I did, you’ll discover a two-part Stratfor series on the role of landscape, and specifically rivers, in the development of America on the global stage.

Why is this interesting?

Geography is a class most of us laughed off in high school. But the article argues that the particular topography of the United States was a critical component of its success.

The American geography is an impressive one. The Greater Mississippi Basin together with the Intracoastal Waterway has more kilometers of navigable internal waterways than the rest of the world combined. The American Midwest is both overlaid by this waterway and is the world's largest contiguous piece of farmland. The U.S. Atlantic Coast possesses more major ports than the rest of the Western Hemisphere combined. Two vast oceans insulated the United States from Asian and European powers, deserts separate the United States from Mexico to the south, while lakes and forests separate the population centers in Canada from those in the United States. The United States has capital, food surpluses and physical insulation in excess of every other country in the world by an exceedingly large margin. So like the Turks, the Americans are not important because of who they are, but because of where they live.

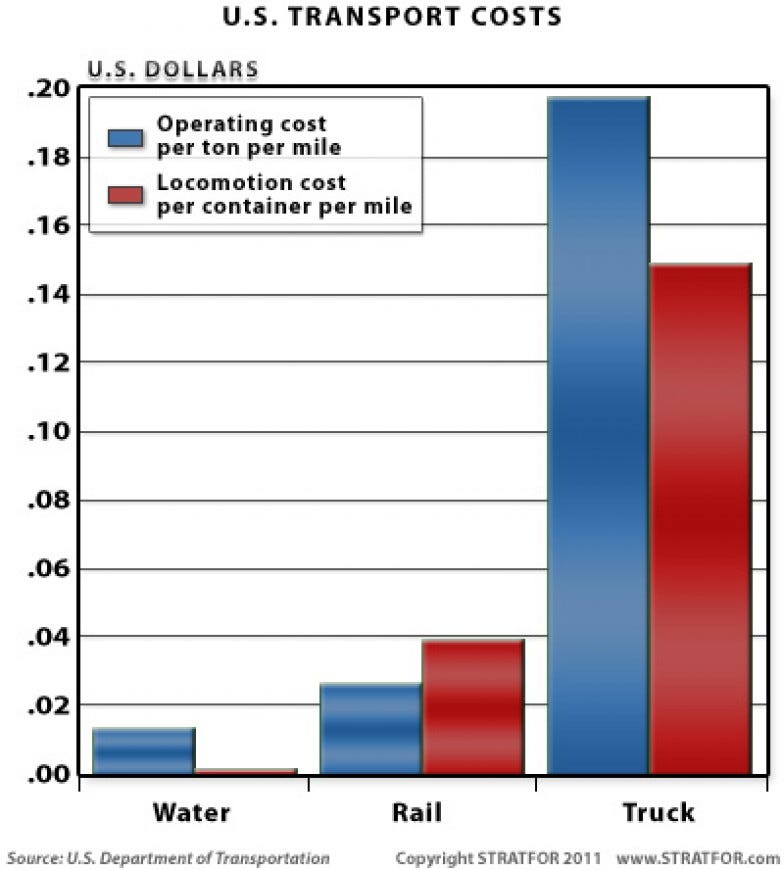

It would be naive to suggest it was rivers alone that pushed the United States to global superpower status. The country was inhabited by Native Americans long before Europeans showed up and a huge part of the economic engine that propelled America was slavery. The country is also rich with coal, timber, and oil. When we talk about the natural resources of a country, however, we seldom mention its waterways. But moving things by water is a lot cheaper than moving things by land, and the US happens to have an amazing artery in the Mississippi, which ultimately connects to five other river systems, the Missouri, Arkansas, Red, Ohio, and Tennessee.

The unified nature of this system greatly enhances the region's usefulness and potential economic and political power. First, shipping goods via water is an order of magnitude cheaper than shipping them via land. The specific ratio varies greatly based on technological era and local topography, but in the petroleum age in the United States, the cost of transport via water is roughly 10 to 30 times cheaper than overland. This simple fact makes countries with robust maritime transport options extremely capital-rich when compared to countries limited to land-only options. This factor is the primary reason why the major economic powers of the past half-millennia have been Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Outside the facts of miles of rivers and costs of shipping, the piece argues that you can look at much of American geopolitics through the lens of ensuring the country’s rivers, and the larger bodies that feed them, are safe. Take Cuba, for instance. “Just as the city of New Orleans is critical because it is the lynchpin of the entire Mississippi watershed,” the article explains, “Cuba, too, is critical because it oversees New Orleans' access to the wider world from its perch on the Yucatan Channel and Florida Straits.” While we don’t control the country, it has been a priority to ensure a larger adversary couldn’t gain a strategic position that could cut off New Orleans, and with it the value of America’s internal waterways.

Clearly, it wasn’t rivers alone that led to the development of both the American economy and its place on the global stage, but they played an important role in how we got to now. (NRB)

Slide of the Day:

From the fun Bloomberg breakdown of Mayoshi Son’s PowerPoint art. (NRB)

Quick Links:

How to intentionally send a spam mail to someone’s spam box. Thx Rex for the link. (CJN)

Long range soccer goals (CJN)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).