Daniel Oberhaus (DMO) is a staff writer at Wired magazine where he covers space exploration and the future of energy. He writes a newsletter about artificial intelligence and psychiatry called Strangemind. Previously he wrote the WITI battery edition.

Daniel here. About a year and a half ago, I found myself lying on a couch in a back office at Johns Hopkins University having one of the strongest psychedelic experiences of my life. The office I was in had all the hallmarks of a living room—soft lighting, tasteful art on the walls, an oriental throw rug—but it was actually a laboratory for studying people under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs. In this instance, I was the 12th and final volunteer in a first-of-its-kind study designed to image the brains of neurotypical individuals as they tripped on salvinorin A, the psychoactive chemical in a plant called salvia divinorum.

This trip was a test run to prepare me for the main event the following day, when I would be put into an MRI machine and given a comparable dose of salvinorin. As anyone who has ever tried salvia divinorum knows, it can be a difficult experience even under the best of circumstances. The hallucinations come on rapidly—usually within 30 seconds of exhalation after smoking it from a pipe—and can cause the user to lose contact with base reality. The trip only lasts a few minutes, but it's incredibly intense. And as I would soon find out, an MRI machine is about the last place you’d ever want to trip. For those of you who have never had a doctor use magnets to peer into your skull, it involves laying almost perfectly still in a very confined space for more than a quarter-hour while a hulking machine makes deafening otherworldly sounds.

But as a longtime advocate of psychedelic research, I had decided to loan my brain to science in the hopes that it could shed some light on this poorly understood substance. Although salvia is typically thought of as a recreational drug, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that its active ingredient— salvinorin A— might have beneficial medicinal qualities. Perhaps the most noteworthy application is its potential role as an alternative to opioids for pain relief and a treatment for opioid abuse since it appears to act on the same receptor, which is almost totally unique among psychedelics. But before salvinorin can become a medicine, neuroscientists need to understand what it’s actually doing in our brain.

A few weeks ago, I reached out to the researchers, who told me they were in the final stages of preparing the data from the experiment for publication. No one has ever observed a human brain tripping on salvinorin before, so no matter what they find, it will be groundbreaking. And with any luck, it could forge a path toward life-saving medications.

Why is this interesting?

Salvia divinorum is endemic to the cloud forests of southern Mexico, where indigenous Mazatec shamans have used the plant ritualistically for generations. It was first introduced to westerners and scientifically described in the 1960s after Gordon Wasson and Albert Hofmann (the famed discoverer of LSD) separately traveled to Mexico to learn about indigenous rituals involving hallucinogens and took a few specimens of the plant back with them for further study. As they discovered, this so-called “the diviner’s sage” is a member of the salvia genus, which is the largest genus in the mint family. Many species of salvia can be found in gardens across the US and are admired for their flowers and aroma. But only salvia divinorum produces a psychoactive chemical called salvinorin A that can induce intense hallucinations when smoked or chewed.

Salvia divinorum is also strange in that it rarely produces seeds. The only way to propagate the plant is with clippings, so it is essentially impossible to crossbreed new strains as you might with other psychoactive plants like cannabis. This means that any salvia divinorum plants you encounter in the US today are highly likely to be the distant offspring of one of the original plants brought back by Hofmann and Wasson half a century ago. Because of the challenges associated with cultivation, salvia divinorum remained an underground phenomenon in the psychonaut community for decades. To get some, you had to know the right people.

The internet changed everything. All of a sudden anyone who was interested in salvia could connect with a grower online. It also helped that the plant was totally legal, which facilitated its spread. Unlike cannabis, coca, and psilocybin, salvia divinorum had avoided scheduling by the DEA partly because it was so rare and partly because many people find its effects deeply unpleasant, which made it unlikely to be abused. By the late 90s, anyone over the age of 18 could procure salvia at their local head shop and for many people it became their introduction to psychedelic drugs.

But increased access to salvia also brought increased scrutiny. Viral YouTube videos like “Gardening on Salvia” and a litany of others showing teenagers (including Miley Cyrus) hitting salvia from a bong and almost instantly going catatonic attracted the attention of lawmakers and concerned parents. Salvia was demonized and many states passed legislation to outlaw the plant. It appeared that salvia, like so many psychedelics before it, was going to be made illegal before scientists had a chance to understand this bizarre and potentially medicinal drug. It was only because the neuroscientist Roland Griffiths, who now leads the psychedelic research program at Johns Hopkins, made an impassioned plea in defense of salvia to Maryland’s congress that the drug avoided being outlawed in the state, which would have effectively killed the salvia research program I participated in at the university.

If you or anyone you know has ever tried salvia, there’s a good chance that it was an uncomfortable experience at best or a terrifying experience at worst. This was certainly true for me. By the time I enrolled in the Johns Hopkins study, I had tried salvia on several occasions as a teenager and it sucked every single time. But as I discovered last year, a salvia trip can also be an incredibly beautiful and meaningful experience when it’s conducted in a safe environment with an experienced guide. I don’t know what the researchers at Johns Hopkins will find in my brain scans, but it's clear that salvia has a lot to teach us if we allow ourselves to become students. (DMO)

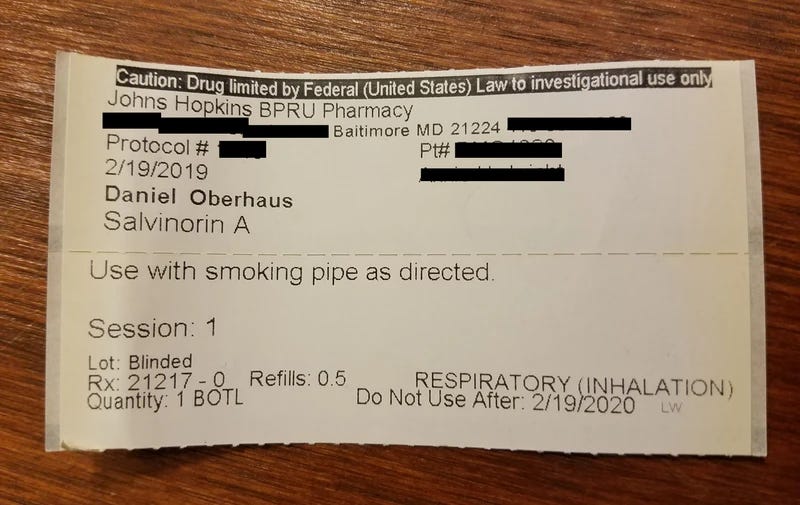

Prescription of the Day:

As a participant in the Johns Hopkins trial I was issued a prescription for a salvinorin A. It’s not often a doctor suggests you smoke anything, much less a hallucinogen. (DMO)

Quick Links:

Why salvia is changing the way chemists think about chemicals (DMO)

The incredible true story of the most brazen bank heist in Argentina (DMO)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Daniel (DMO)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).