Why is this interesting? - The Stamps Edition

On mail, meaning, and the artwork that appears on US postage

Praveen Fernandes (PF) is my brother-in-law and someone I have been trying to convince to write a WITI since we got started last year. His bio is far longer than I could list here, but briefly, he’s a lawyer, advocate, former Obama administration appointee, art lover, and a great uncle! Hugely happy to have him writing here. - Noah (NRB)

Praveen here. I enjoy old-school correspondence. Yes, handwritten letters, placed in envelopes, stamped, and then placed in mailboxes. I savor the idea that a letter I have touched will travel thousands of miles, across seas and time zones, and finally arrive at the home of loved ones, where it will be touched by their hands; atoms that I have rearranged on the page will be further rearranged by them in an act of communion, meaningful even before they get to the letter’s substance. I appreciate that loved ones know it is a letter from me even before opening it, as they recognize my handwriting; in turn, for a handful of family members and friends, I can instantly identify their handwriting. I realize that I’m a statistical outlier in an era of email and text messages, both of which are admittedly more efficient channels of communication and ones I use all the time. My relationship with mail is driven more by emotion than by logic. Stamps are a part of that.

I was reminded of this emotional connection this past December, when I was about to mail my holiday cards and agonized about which stamps to buy. In the end, I selected stamps featuring artwork from “The Snowy Day,” a beloved children’s book by Ezra Jack Keats, which won the Caldecott Medal in 1963, making it the first book with an African-American protagonist to win a significant children’s award. But the truth is, I was temporarily frozen by my winter stamp choices. There were Winter Berries, Holiday Wreaths, and Poinsettias, and that is before one even gets to the stamps that mark winter holidays, such as Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, or Lunar New Year. Happily, there was a diversity in the offerings that would have been unimaginable in my youth.

Why Is This Interesting?

I spend a lot of time at my day job thinking about the arc of constitutional progress, meaning the way in which the United States Constitution, through its many amendments, has been strengthened and become more inclusive, reflecting our nation’s conversations about equality and liberty, and about the metes and bounds of the American family. However, the Constitution is only one locus for this national discussion; our cultural institutions and products, and yes, even our stamp subjects, reflect this conversation and can trace an arc of progress. (To cite just two examples, in 2006, children had their first chance to send letters with an Eid stamp, and in 2016, children had their first chance to send letters with a Diwali stamp, expanding people’s ideas about what could qualify as an American holiday and what traditions our friends and neighbors observed.) I became curious about how the United States Postal Service (USPS) chooses stamp subjects.

As is often the case with important matters, there’s a committee associated with it. In this instance, it is the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAC), which advises the United States Postmaster General (PMG), who heads the United States Postal Service (USPS). The USPS describes the committee’s function as follows:

Using their collective expertise in history, science, technology, art, education, sports, and other areas of public interest, CSAC members consider and then recommend stamp subjects to the PMG, who makes the final selections.

There is a process, involving CSAC consideration of the proposals at quarterly meetings. And the process is not hasty—stamp programs and subjects are planned two to three years in advance. The USPS has established some clear criteria, including, but not limited to: (1) that the subject be American (although “other subjects may be considered if the subject had significant impact on American history, culture, or environment”); (2) that if the subject is a person, the person is deceased and died at least 3 years before the proposal; (3) that if the subject is the anniversary of a historical event, it should be in multiples of 50 (50th anniversary, 100th anniversary, etc); and (4) that the subject be positive, as “negative occurrences and disasters will not be commemorated on U.S. postage stamps.” Additionally, presumably to avoid any issues relating to entanglement with religion, the USPS will not issue stamps “to honor religious institutions or individuals whose principal achievements are associated with religious undertakings or beliefs.”

Any member of the public can submit a proposal for a stamp subject. And since “no in-person appeals, phone calls, or e-mails are accepted,” one is reminded that a proposal must be written and mailed using the USPS. (But, of course!) Roughly 40,000 ideas are submitted each year, and of these, roughly 25 proposals are selected by the CSAC and passed on to the Postmaster General for approval. Individuals whose proposals are not selected by the CSAC need not lose heart, as they can resubmit a proposal after a three-year interval. Stamp campaigns have lasted many years and involved numerous advocacy organizations. For instance, when the Marvin Gaye stamp was issued on April 2, 2019 (on what would have been Gaye’s 80th birthday), it represented the culmination of a campaign begun in 2003 to honor the music icon (often referred to as the “Prince of Soul”) and which involved both the Motown Alumni Association and the Marvin Gaye USPS Stamp Initiative, an organization founded by superfan Carla Johnson. As Johnson said in an article in The Charlotte Post, “…when we were finally able to see something that had been denied twice, we felt like we had definitely made history and I was excited to be a part of that.”

While the professional artists with which the USPS contracts to produce stamp artwork are compensated, individuals who have submitted successful stamp subject proposals receive no credit or financial compensation. But I’m not sure anyone can put a price on having played a role in what we celebrate as part of our American heritage and who we honor as part of the American family. (PF)

Book of the Day:

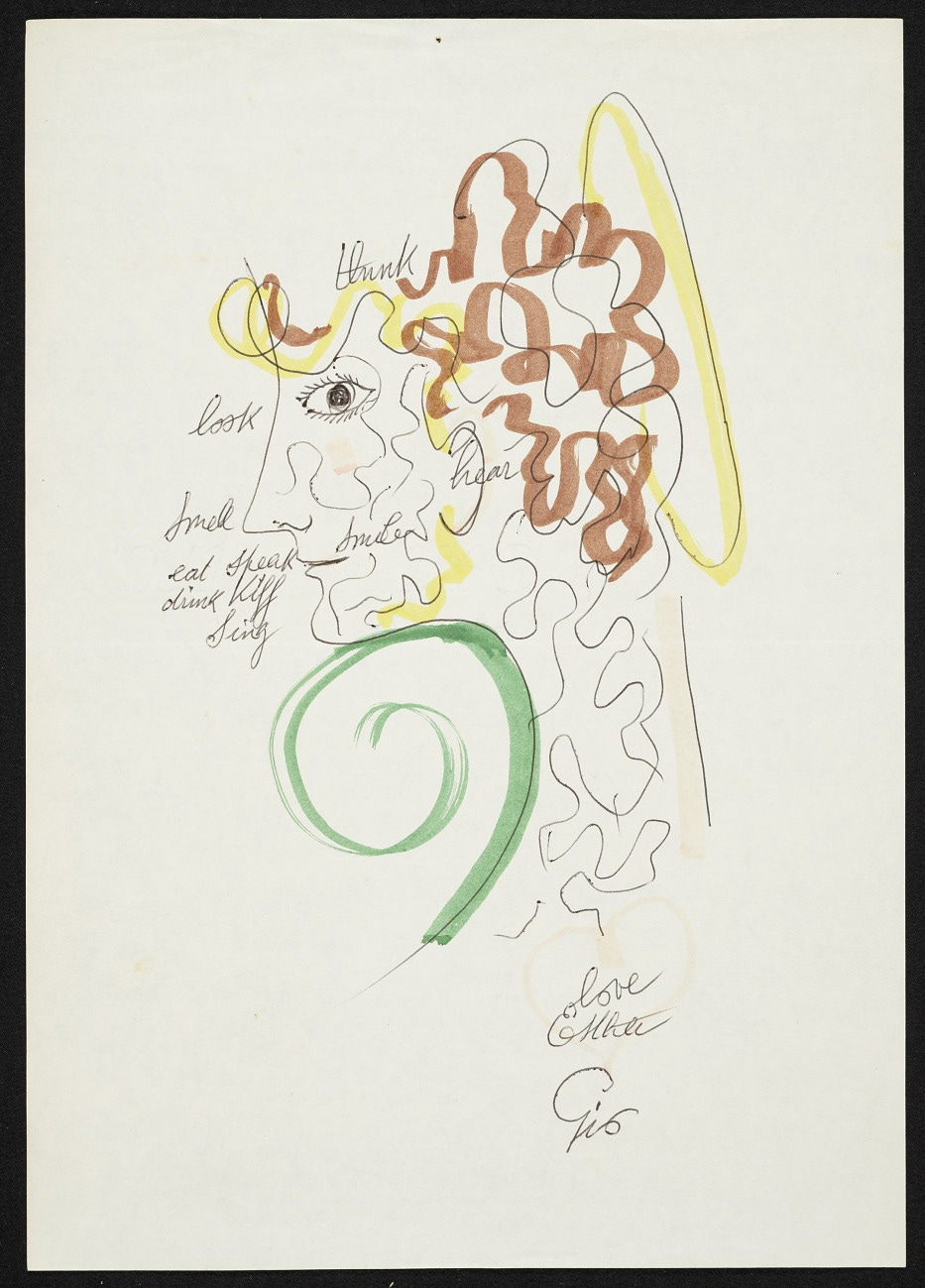

There are many great collections of correspondence between famous writers, such as the compelling “Words in Air,” which is the complete collection of the decades of letters shared between the poets Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell. But have you wondered about letters from people known more for images? “More Than Words: Illustrated Letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art” collects illustrated letters from artists and architects. For instance, a 1978 letter from the architect and furniture designer Gio Ponti to American architectural historian Esther McCoy, a 1981 thank-you note from painter Edith Schloss, a 1971 letter from artist and social activist Miné Okubo, or a 1913 three-dimensional letter from illustrator Alfred J. Frueh to his future spouse Giuliette Fanciulli.

Quick Links:

Few intellectual property dispute stories have happy endings. This New York Times piece recounts one of those rare tales, about a brief naming kerfuffle between an indie-rock band (the Postal Service) and an independent federal government agency (the United States Postal Service). (PF)

A less happy tale about the Statue of Liberty, a sculptural replica in Las Vegas, a stamp, and a choice that cost $3.5 million. (PF)

A touching 2014 Washington Post article about the issuance and dedication of the Harvey Milk stamp. (PF)

History.com author’s opinion about the 11 most controversial stamps in United States history (PF)

International Correspondence Writing Month (affectionately known as “InCoWriMo”) involves a pledge to write a letter a day in February, the shortest of months (PF)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Praveen (PF)

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).