Since it’s Thanksgiving week we’re going to try something different. Monday through Wednesday will be normal editions, but for Thursday we’re going to send around interesting reads for the long weekend (and take Friday off). We’re looking for links from readers, so if you’ve got something you think others would enjoy reading (doesn’t have to have anything to do with Thanksgiving), please use this form to contribute. Thanks! - Noah (NRB)

Noah here. A few weeks ago Robin Sloan wrote an excellent piece for his excellent newsletter on the new look of Fortnite:

Since the game’s creation, Fortnite’s island has been its great constant: eroded, impacted, and rezoned, yes, but always with the same basic shape, and a profile like a kindergartner’s landscape doodle: every hill and mountain a steep spike. It was a cartoon; that was part of its appeal.

Now, the island has grown up. A few landmarks remain, planted in new locations like scattered seeds, but the terrain is totally different, and it’s the terrain that is the star. The new island’s geography is softer, more natural. Mountains flow into moraine. Hills flatten into meadows. Draws empty into creeks.

...

The new environment is plainly pastoral. There’s more open space. The farms have become more detailed, with apple orchards and rows of trellised tomatoes.

Butterflies dance in the meadows.

Why is this interesting?

The unique look got me thinking about one of the more interesting things I’ve read about the design of videogames. In a 2017 Atlantic article, Ian Bogost argues we need to cut short the conversation that videogames are the 21st century’s movies. “If there is a future of games, let alone a future in which they discover their potential as a defining medium of an era,” he wrote, “it will be one in which games abandon the dream of becoming narrative media and pursue the one they are already so good at: taking the tidy, ordinary world apart and putting it back together again in surprising, ghastly new ways.”

And while that’s an intriguing argument and one I tend to agree with (as many a media theorist has pointed out, almost any new medium starts trapped by the shackles of its predecessors), it was something else he said in the piece that really stood out. Specifically, he explains why games have spent so much time obsessed with a post-apocalyptic world—and it wasn’t for a reason I ever would have thought of:

In retrospect, it’s easy easy to blame old games like Doom and Duke Nukem for stimulating the fantasy of male adolescent power. But that choice was made less deliberately at the time. Real-time 3-D worlds are harder to create than it seems, especially on the relatively low-powered computers that first ran games like Doom in the early 1990s. It helped to empty them out as much as possible, with surfaces detailed by simple textures and objects kept to a minimum. In other words, the first 3-D games were designed to be empty so that they would run.

An empty space is most easily interpreted as one in which something went terribly wrong. Add a few monsters that a powerful player-dude can vanquish, and the first-person shooter is born. The lone, soldier-hero against the Nazis, or the hell spawn, or the aliens.

In other words, the story was a function of the limitations of the medium, not vice versa. Seldom do we get such a straightforward example of the medium as the message. (NRB)

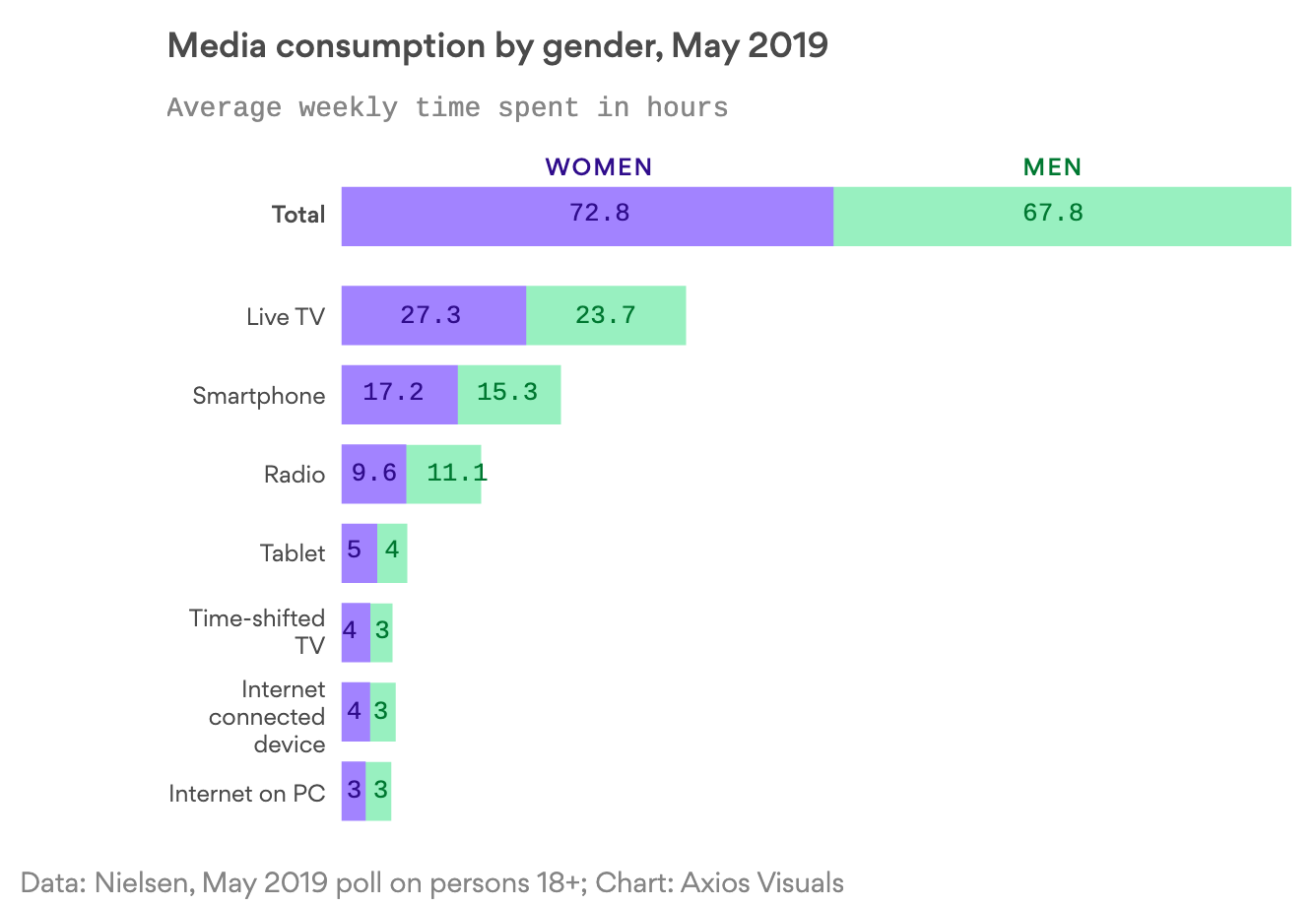

Chart of the Day:

Media consumption by gender from Axios Media Trends. (NRB)

Quick Links:

How to Spy on Your Neighbors With a USB TV Tuner. “A few years ago, French researchers showed that even individual keys being pecked on computer keyboards generated unique radio fingerprints.” (NRB)

What future artificial intelligence will think of our puny human video games (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

PS - Noah here. I’ve started a new company and we are looking for a sr. backend engineer to join the team. If you are one of those or know anyone who is great, please share. Dinner’s on me at a restaurant of your choice if you help us find someone.

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).