Another themed edition. This one is all about books published in 2018. One of the things Colin and I have been talking a lot about is making sure this email isn’t reliant on the “news peg”: the of-the-moment thing that drives media cycles. So today, for no reason other than there are lots of good books from last year, we’re going to revisit some of our favorites. This list is by no means exhaustive (most if the books we read in 2018 were published years earlier), but it’s a fun way to highlight a few favorites. - Noah (NRB)

Also: thank you for all of the support, kind notes, and mega interesting links that people have been sending. It is most appreciated. As always, drop a line if you’d like to guest. - Colin (CJN)

Noah here. Nearly every year-end best books list included Tara Westover’s Educated, a memoir about growing up in an ultra-religious Mormon household that was completely disconnected from the outside world. She eventually escaped, both physically and mentally, when she went to Brigham Young University (and eventually Cambridge and Harvard). Westover was named to the Time 100 (with a write up from Bill Gates), is giving this year’s commencement address at Northeastern University, and has gotten shout outs from both Barack and Michelle Obama in the last twelve months.

Why is this interesting?

While the book is amazing (I read it this year with all the expectations piled on and still felt that way), the majority of reviews I read missed what makes it work. That’s because most of them focused, in one way or another, on the similarities between Educated and JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, the book every 2017 newspaper article cited as it came to grips with the election of Donald Trump. While I admittedly skipped Vance’s book, I find the comparison odd because Educated isn’t really a book about poverty or even religion in America. It’s much more about reflection and learning and how that happens over time. While it’s not quite how I would put it, this New Yorker review comes closest to the book I read:

This story, remarkable as it is, might be merely another entry in the subgenre of extreme American life, were it not for the uncommon perceptiveness of the person telling it. Westover examines her childhood with unsparing clarity, and, more startlingly, with curiosity and love, even for those who have seriously failed or wronged her. In part, this is a book about being a stranger in a strange land; Westover, adrift at university, can’t help but miss her mountain home. But her deeper subject is memory. Westover is careful to note the discrepancies between her own recollections and those of her relatives. (The ones who still speak to her, anyway. Her parents cut her off long ago.) “Part of me will always believe that my father’s words ought to be my own,” she writes. If her book is an act of defiance, a way to set the record of her own life straight, it’s also an attempt to understand, even to respect, those whom she had to break away from in order to get free.

But there’s something more than that. I suspect part of what makes the book so impressive is that Westover had childhood journals to lean on. She transformed those events using her immense writing skills to tell the story of her life almost entirely non-reflectively (at least until she reaches a point in her life where reflection becomes possible). As she learns more about herself, much of it a result of having her eyes opened in classrooms of higher education, she begins to layer those insights on top of her experiences and reinterpret them: communicating truths about all of us in the process. If she hadn’t written those journals, would she have had the ability to recall her experiences as effectively? I think that’s unlikely. Memories tend to become colored over time by any number of life experiences, making them less reliable foundations for the development of theoretical foundations. (Westover makes this point a few times in the book, actually.) But in the end it’s not just the memories that make the book special, it’s the exploration of those memories in a search for truth that feels so raw and real.

This is particularly true as she explores the violence in her childhood, which is particularly affecting because it’s written in that mostly non-reflective way I describes. As she explained in a recent interview, “One of the things I wanted to communicate a little bit by telling this story was to help people understand something it took me a long time to understand, which is that people are incredibly complicated, and if someone was only violent, it wouldn't be so hard to walk away.” That truth, both related to violence and not, is the string that ties the book together. In the end I suspect what people saw in common with Hillbilly Elegy is the reality that people are complex creatures. But in the end almost every book is about that.

Go read Educated (or listen to the excellent audiobook.) (NRB)

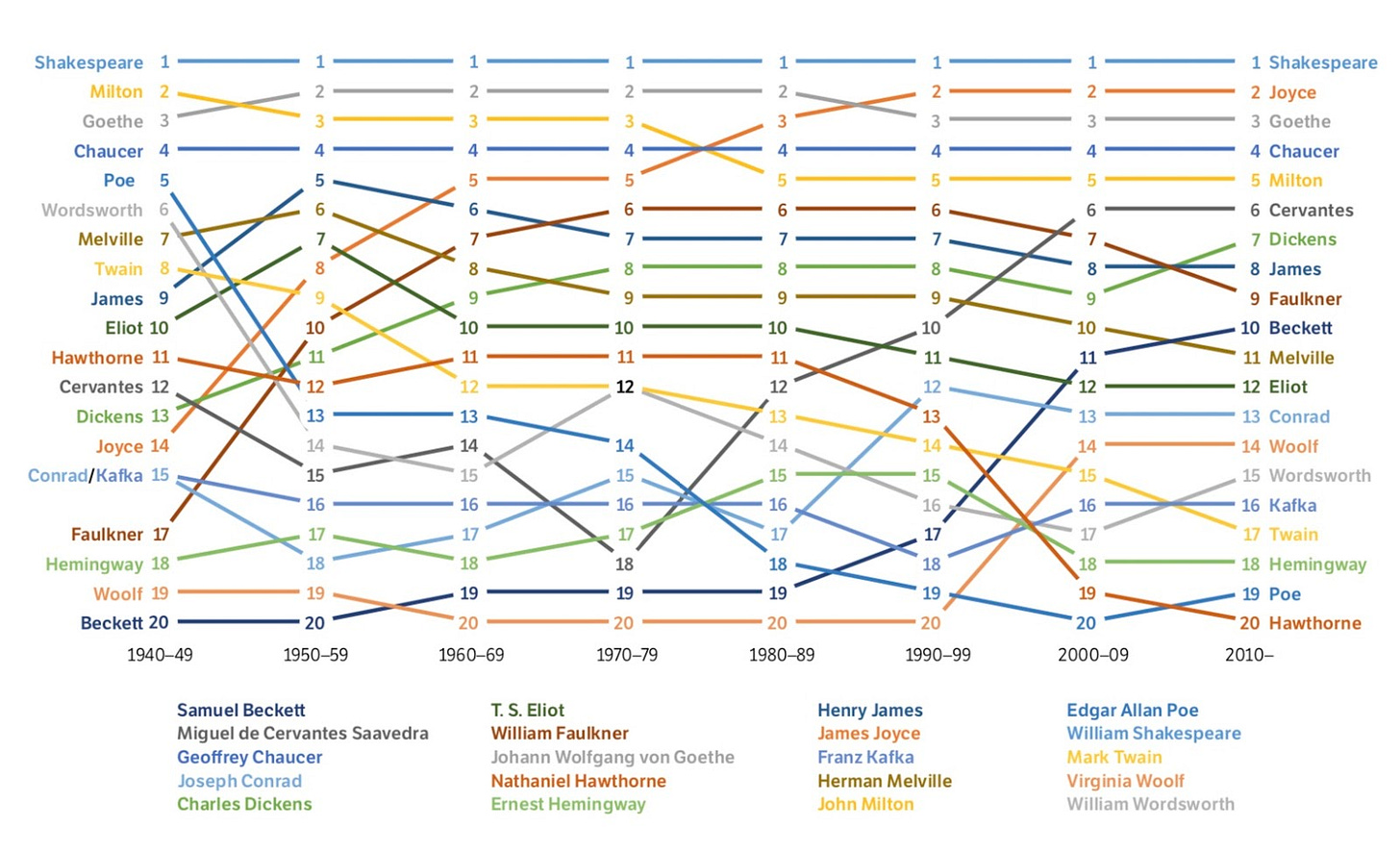

Chart of the Day:

From the Stanford Literary Lab, the changing canon: “Within the MLA, for instance, critical attention has migrated over the years, not only because new authors enter the canon, but because at times former mainstays and mediocrities have switched places. Figure 9 shows a version of this in miniature, in the changing rankings by decade among the authors (from our list) with the 20 highest current MLA scores.” (NRB)

Quick Links:

I ripped through My Sister the Serial Killer when I read it earlier this year. It’s the first novel by Oyinkan Braithwaite and, as the title suggests, is a fictional account of a two sisters, one of them with a predilection for murder. I discovered it on Lit Hub’s favorite books of 2018 writeup. (NRB)

I loved Ben McIntyre’s The Spy and the Traitor, which was about one of the highest level KGB defectors that worked with MI6 for years. Reads like a real-life John Le Carre novel. (CJN)

If you know me personally you know that I went into a deep physics rabbit hole last year. It started with E=mc2: A Biography (published in 2001) and quickly moved into the quantum realm. While I’m far away from an expert, my favorite book of the genre, and one of my very favorite of the year was Beyond Weird: Why Everything You Thought You Knew about Quantum Physics Is Different by Philip Ball. The core idea of the book is that on one hand quantum physics is less hard to understand than many would have you believe, but on the other the challenges in comprehension mostly lay in the fact that our language was developed in a Newtonian world. If you’re not quite ready to jump in, start with Ball’s talk at the Royal Institution on the same topic. (NRB)

Lawrence Wright is a hero, having written the Looming Tower, one of the smartest books about radical Islam. He turned back to America to write a book about Texas that wraps a personal narrative around an important state for its changing demographics and role in the American story. (CJN)

I was gripped by Patrick Radden Keefe’s New Yorker story last summer about Astrid Holleeder, sister-turned-informant of the biggest mobster in Amsterdam. It was done, in part, because Holleeder’s memoir, Judas, was coming out in English in the US. It’s a disturbing look at the hell her brother (who is most famous for kidnapping Freddy Heineken in 1983) put her and the family through and how she finally decided to help put him away. (NRB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)