Dave Kienzler (DBK) is a lawyer working on natural resources for sustainable development, human rights, and socially responsible investing. He’s served as a legal advisor in the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar and in the Government of Malawi as those countries developed their oil and mineral sectors. He once had the misfortune of being Noah’s college roommate. Blogs (very) occasionally here. Open to consulting opportunities.

Dave here.Back in July Noah discussed investment opportunities created by climate change, but the big debate in this space in the last decade is what to do with existing investments in companies that contribute most directly to climate change—specifically fossil fuels—with most of the debate has centered on divestment.

The topic returned to headlines this summer when Norway’s sovereign wealth fund received the government’s permission to divest $13 billion of its fossil fuel holdings. It will gradually sell off $8 billion in oil and gas and $5 billion in coal. At the same time, the government doubled the ceiling for the Fund’s green energy investments to $13.7 billion. The world’s largest pension fund ($1.06 trillion) selling off an entire asset class would be major news in any circumstances, but the story took on additional momentum as Norway struggled to explain its rationale, insisting that the move was an attempt to curb the country’s financial risk as a major petroleum producer, not about climate policy.

Why is this interesting?

The Fund’s difficulties in explaining this seismic investment shift highlights a problem that has plagued the divestment discussion since its inception: What is divestment intended to accomplish?

Similar movements around Sudan, Iran, and tobacco have illustrated that as a tool to effect changes in corporate behavior (the radical changes necessary to be meaningful in fighting climate change), divestment is complicated and often limited in its success. Fossil fuel companies are simultaneously too big to have their share prices affected by divestment and arguably too lucrative for asset managers to divest from while still fulfilling their fiduciary duty. Norway’s fund saw 14.1% returns from its oil and gas investments in the first quarter of 2019. Furthermore, an investor who divests loses any influence it may have over the company as an activist shareholder. So, changing fossil fuel company behavior often isn’t a strong enough argument on its own, and what else divestment can accomplish varies depending on the type of investor.

University endowments, so often the focal points of divestment activists, and socially responsible/faith-based investors offer some clues. If the goal is to “break the hold that the fossil fuel industry has on our economy and our governments”, a university selling off its endowment investments in an oil company won’t be successful. Even the largest university endowment, Harvard’s, which totals $38.2 billion would not move those companies' stock prices at all, much less impact prices enough to force any of them to alter their central business model. On the other hand, universities play a large role in thought leadership and shaping and informing public debate, in which case divesting from fossil fuel companies—or even just campus debate on divestment—can advance the national dialogue. It can be argued that because of their role in molding the next generation of American leaders, universities have to set an example and so have a responsibility to hold themselves to the highest possible standards when making investment decisions. For socially responsible (SRI) and faith-based investors the clear case for removing objectionable companies or industries from their funds is aligning their investment decisions with their values. Screening funds of companies/industries with business models that are inherently destructive (tobacco and weapons are other commonly screened industries) goes back decades, and with SRIs and faith-based investors leading the way, the pool of investors who are incorporating more socially- and environmentally-conscious considerations into their decision-making is growing rapidly. For these institutions, divestment can achieve a range of positive indirect and long-term impacts even if it is not the most effective approach to changing corporate behavior in the short-term.

But for most investors, the argument is harder. The only accomplishment that matters to Wall Street is a larger bottom line, and even institutional investors that are often targets of divestment activists, like state retirement and pension funds, are legally limited by the requirements of their fiduciary duty. For those investors, divestment has to provide a financial benefit. Increasingly a viable financial argument can be made, particularly to investors with long horizons, that divestment mitigates the risk to portfolio performance presented by the stranded assets and/or the drop in the value of fossil fuel companies created by a lower-carbon future. Which brings us back to Norway.

Norway was already one of the first state-owned funds to incorporate ethical, environmental and social issues into its decision making and it has been debating an end to its fossil fuel investments since 2013. It could argue that divestment is the logical next step for an ethical investment leader. A fund that owns +1% of the world’s stocks divesting from fossil fuels sends a serious signal to the market, significantly advances the dialogue on investing in oil and gas in the face of climate change, and potentially prompts some (albeit almost certainly limited) changes from fossil fuel companies. There is also the strong financial argument that the move will limit the massive exposure of an oil-supported Fund invested heavily back into fossil fuels to a permanent drop in carbon prices.

But many in government recoil at the idea of the Fund being politically activist, which is why the messaging on the decision has been so contradictory and unconvincing. After all, hedging against a permanent carbon price drop is an argument entirely rooted in the acceptance of climate change and the contribution to it of fossil fuels. The world’s industry-leading fund taking such an industry influencing action while refusing to own the basis of its decision-making shows us just how far we are still from the kind of investor shift we are currently seeing with coal. (DBK)

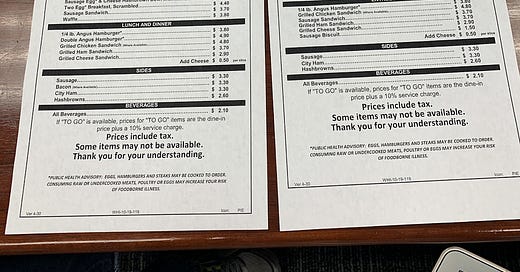

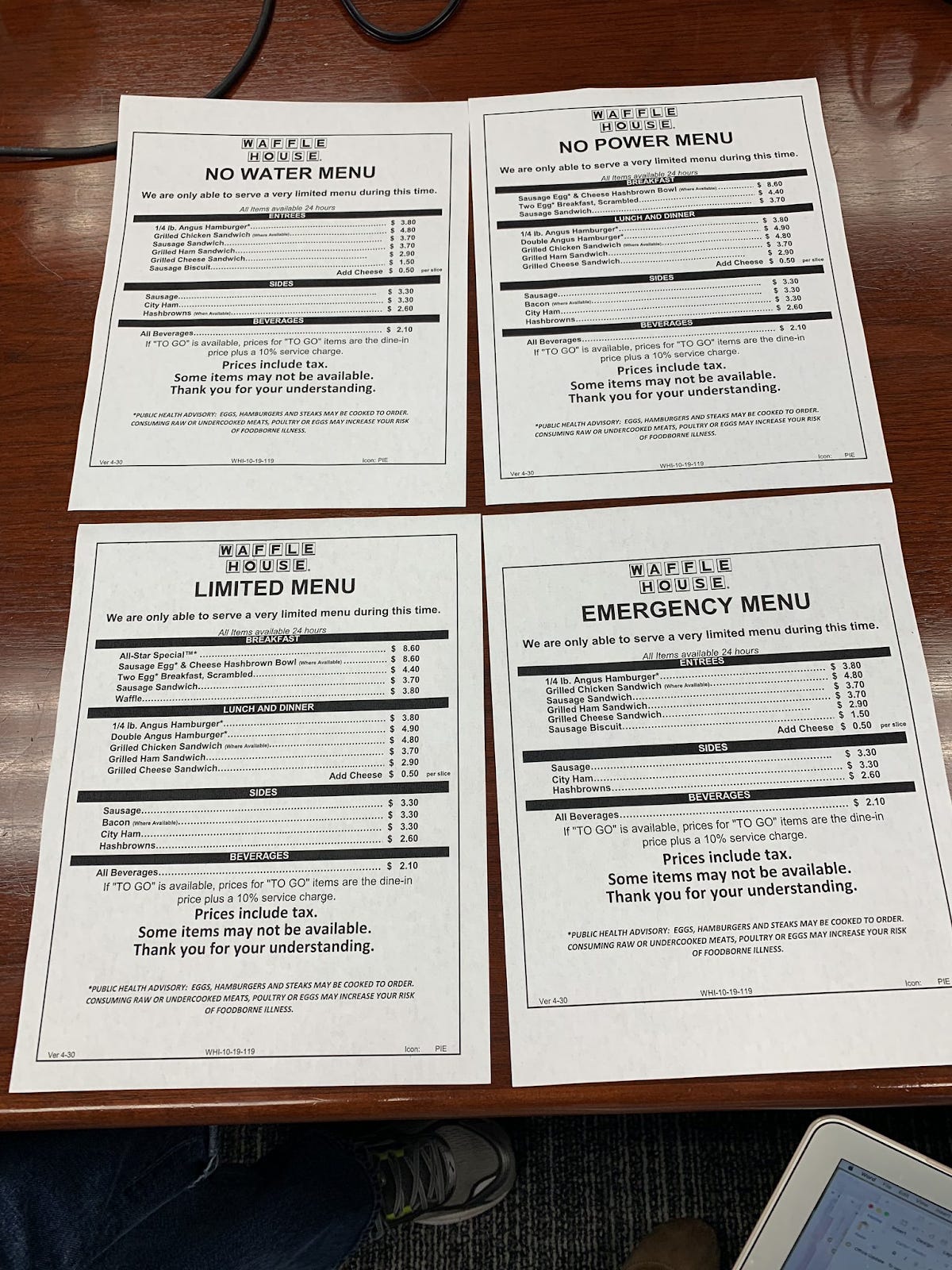

Photo of the Day:

This photo of Waffle House emergency menus was making the Twitter rounds (and got a Kottke link). From the associated article: “Waffle House restaurants are often used to gauge the magnitude of disasters in the Southeast: If a store is open, your community has been spared. If the store is open but has a limited menu, you've probably gotten some damage. If the store is completely closed, you’re in a disaster zone.”

Quick Links:

Discussion about investing in fossil fuel companies is good and important, but state-owned oil companies – including Saudi Aramco, the world’s most profitable company – actually dominate the market and are responsible for more than half the world’s production. (DBK)

Companies are increasingly going to try and incorporate climate change messaging. Many are going to screw it up badly. Luckily, Natty Light is there to call them out. (DBK)

For those of you without an appreciation for the beer America was built on, here’s a look at the history of climate change and wine. (DBK)

In 1989, the Soviet Union paid Pepsi for its sodas with submarines, briefly making the company the world’s 6th largest submarine navy. It also paid in vodka. Pepsi passed it on in 1996 when it advertised a Harrier jet if you redeemed 7 million Pepsi points. Someone actually tried! It ended in a lawsuit. (DBK)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Dave (DBK)